Personal Canons: Dinotopia

In addition to my own reflections and guest posts from brilliant folks in the writing community, the Personal Canons series will also feature essays purchased from among the many dazzling submissions I received in response to my open call. Last time, Amy Tenbrink wrote about the work of Nnedi Okorafor. Today, I’m thrilled to feature Filip Hajdar Drnovšek Zorko.

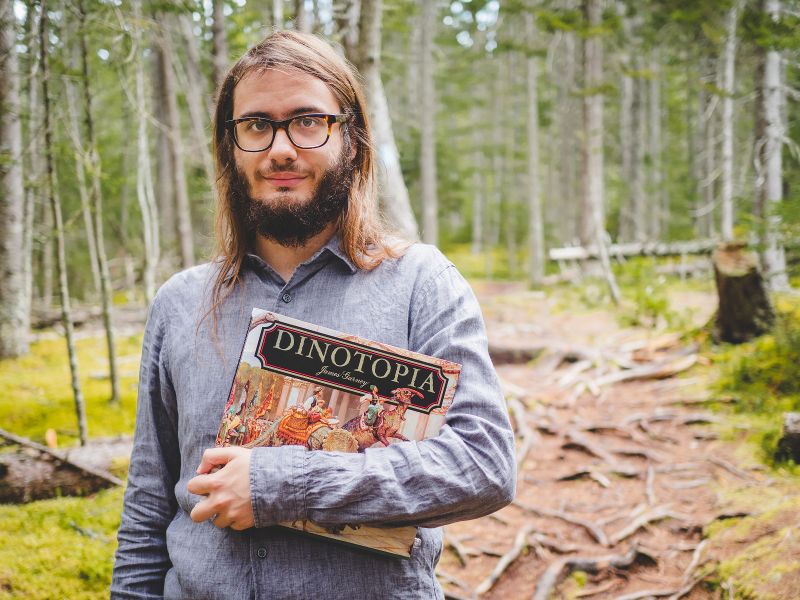

Filip Hajdar Drnovšek Zorko is a Slovenian-born writer and translator currently living in Maine. He realises his name is a bit confusing and would like you to know that "Drnovšek Zorko" is the surname. In 2019 he attended Clarion West, and his fiction has appeared in Clarkesworld and Escape Pod. You can follow him on Twitter @filiphdz.

When people comment on my writing, the words I hear most often are optimistic and uplifting. If the comment is of a more critical bent, it might also mention a lack of conflict. The first time I got this feedback was at Clarion West, where each of my stories ended on a hopeful note. I hadn’t thought much of it until then. They were simply the stories I wanted to tell. Then, one day a few months after the end of the workshop, I glanced at my bookshelf and wondered why it had taken me so long to figure it out: the optimism in my writing originates with James Gurney’s Dinotopia.

Dinotopia is one of the few books I have read in both Slovenian and English, a fact which speaks to the level of popularity it enjoyed at the peak of the dinosaur renaissance in the early nineties. Like so many other beloved children’s books, Dinotopia is essentially a portal fantasy, in disguise as the journal of Arthur Denison, a scientist from Boston, who is shipwrecked with his twelve-year-old son William in 1862. Rescued by dolphins and delivered to the uncharted continent of Dinotopia, the two are gradually integrated into a society in which dinosaurs live side-by-side with humans.

Classic portal fantasies—Narnia foremost among them—often take the form of white saviour narratives. Dinotopia averts this trope from the start. Gurney’s lavish illustrations spend as much time on minor details of Dinotopian society as they do on the Denisons. Nor are our protagonists especially privileged by virtue of their status as “dolphinbacks”: when Will declares he wants to become a Skybax (pterosaur) rider, his newcomer status is neither boon nor hinderance. He’s warned that no dolphinback has ever been one; then he’s given a course of study, a route by which he might achieve his dream. There are no shortcuts here. It takes a few timeskips to get him to his goal, and when he gets there, when he and his Dinotopian friend Sylvia ask the instructor Oolu for permission to fly as full-fledged Skybax riders, Oolu replies, referring to their pterosaur partners: ‘You don’t need my permission: you have theirs.’

Gurney’s work on archaeological reconstruction for National Geographic is evident everywhere in the architecture and design of Dinotopia. The human inhabitants (all shipwreck survivors or their descendants) are correspondingly diverse, though one might justifiably point out that the main cast are still disproportionately white. As a child moving between (tragically dinosaur-less) countries, this diversity made sense to me. I saw myself in Will: we were both young enough to effortlessly absorb culture, to adapt to our situation in ways our parents found more difficult.

With the benefit of hindsight, I noticed a deeper nuance. Early in the book, when Arthur is still set on leaving the island, he meets a man called Lee Crabb, nine years’ shipwrecked and obsessed with fleeing a society in which, he claims, dinosaurs subjugate humans. But if dinosaurs come first on Dinotopia, it is only in a literal sense: they were there first. Dinosaurs made room for humans, and over centuries evolved a peaceful symbiosis with them.

This is what Lee Crabb sees as dinosaur supremacy—a world in which a Skybax rider must ask their partner, and not another human, for permission. Here, in other words, is a world in which the arrival of humans did not results in the genocide of the original inhabitants. Here is the lesson that someone accustomed to the privilege of European imperialism cannot live in an equitable society without feeling himself oppressed. Growing up in Australia, the contrast — whether I noted it consciously or not — was stark.

Crabb does not succeed in winning Arthur to his cause. Arthur’s reservations about Dinotopia melt away with a minimum of fuss. He finds a place for himself in Waterfall City. He makes friends, human and dinosaur alike. He sees his son blossoming in Dinotopian society. This is Dinotopia’s secret. It resists conflict at every turn; it sees the beauty in things other books would mine for dramatic effect. When Arthur encounters a dinosaur graveyard, full of Pteranodon scavenging carcasses, the words he uses to describe it are not dark or twisted, but sombre and holy. When he mistakenly injures the Protoceratops translator Bix, he realises her response, out of proportion with the severity of the injury, is born of a society in which violence is all but unknown. Even the population of Tyrannosaurus rex, depicted, inevitably, as antagonists, aren’t evil—they choose to live outside the rest of Dinotopian society. They are treated with wariness but not fear. They can be reasoned with or, if necessary, outwitted. But they are not evil.

One might argue that this is also the book’s most unrealistic aspect. We must suspend our disbelief to accept that Dinotopian society can proceed so gracefully from such a patchwork of pieces. Are dinosaurs truly content to do the heavy labour required of them? The book says yes—their strength is a point of pride, and the work not treated as demeaning. Are humans truly content to collect dinosaur dung for use on their farms? The book says yes—it is a noble and necessary profession. These sorts of details, I admit, sound awfully convenient. Can we, as readers, believe they are true?

Dinotopia has an answer for the sceptics. Arthur himself voices these doubts when he first arrives in Waterfall City, in response to Nallab the librarian’s description of life on Dinotopia. ‘I can’t imagine,’ Arthur says, channelling a sentiment that resonates even more deeply today, when a better future seems farther away than ever, ‘how it could be possible.’ Nallab’s reply offers a blueprint for the optimism that pervades Dinotopia—a blueprint I unknowingly internalised as a six-year-old who only wanted to look at pretty pictures of dinosaurs.

Here is what he says:

‘Oh, it is possible—but only if you do imagine it.’

Personal Canons is a series exploring the works of genre fiction that have shaped us as readers, writers, and people. This series features contributions by established authors, new and aspiring authors, readers, and fans.

Imagine a world that can be better than this one. Do everything you can Go to protests and stand up for change. Sign petitions, as many as you can. Text, call, and email demanding justice — there are templates at that link. Donate money, and if you don’t have money, click here to donate just by watching a video playlist, or click here to donate by playing a game. Subscribe to Fiyah, a brilliant speculative fiction magazine that features stories by and about Black people of the African diaspora. Register to vote (double-check to be sure you haven’t been purged from any voter rolls) (seriously, check again).

Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Member discussion