Use the Corkscrew: On Deploying Every Available Weapon

Madeline Ashby graduated from the first cohort of the M.Des. in Strategic Foresight and Innovation programme at OCADU in 2011. It was her second Masters degree. (Her first, in Interdisciplinary Studies, focused on cyborg theory, fan culture, and Japanese animation!) Since 2011, she has been a freelance consulting futurist specializing in scenario development and science fiction prototypes. That same year, she sold her first novel, vN: The First Machine Dynasty, to Angry Robot Books. It is now a trilogy of novels about self-replicating humanoid robots (who eat each other alive). She is also the author of Company Town from Tor Books, a cyber-noir novel which was a finalist in the 2017 CBC Books Canada Reads competition, and a contributor to How To Future: Leading and Sense-making in an Age of Hyperchange, with Scott Smith. She is a member of the AI Policy Futures Group at the ASU Center for Science and the Imagination, and the XPRIZE Sci-Fi Advisory Council. Her work has appeared in BoingBoing, Slate, MIT Technology Review, WIRED, The Atlantic, and elsewhere.

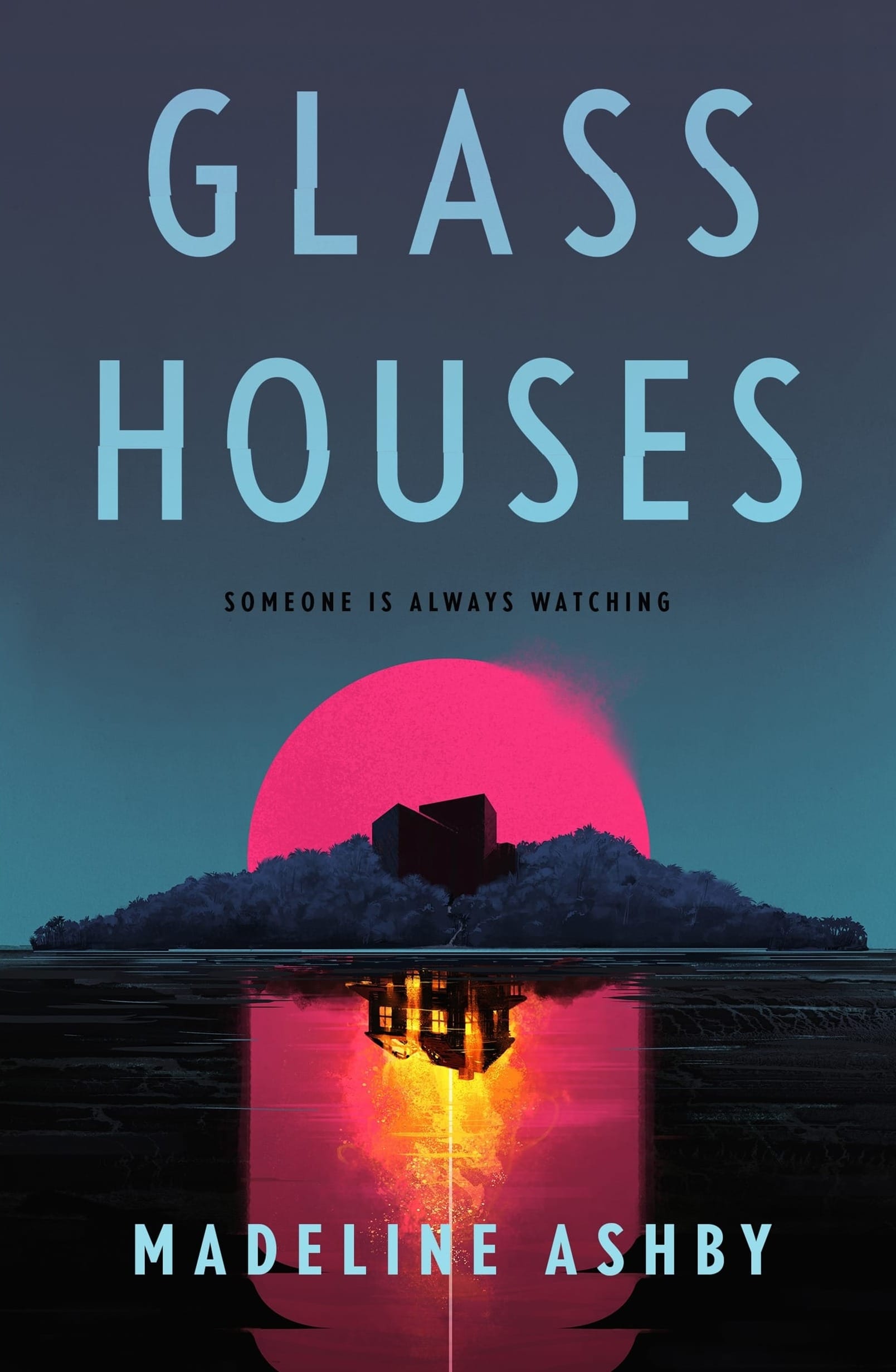

“Every time you turn in another draft, it’s a different genre,” is how my editor Miriam Weinberg at Tor described my issue with writing Glass Houses. My last novel (which concluded my Machine Dynasty trilogy from Angry Robot Books) came out in 2020. But I’ve been on the hook for Glass Houses since 2016. That means I spent seven years wrestling with it. I’ve written about those seven years elsewhere, including the Stone Soup cookbook, which I advise you pick up. Over those years, Glass Houses was, at various points, a near-future science fiction book, a locked-room murder mystery, and a spy novel. But today, I want to talk about ambiguity.

It’s become very popular lately to say that contemporary discourse has no room for ambiguity, or nuance, or shades of grey, or context. This framing positions ambiguity — the quality of being open to interpretation — as something to which we all collectively developed an allergy overnight. But that’s not what happened.

What happened was we started computing. And how we compute influences how we categorize, and how we categorize influences how we understand value.

Anyone can make numbers lie. There are always stats to be juked, maths to be made “fuzzy,” Mercator projections to stretch and skew until they bend foreign policy. There are lies, damned lies, and statistics. Reaganomics, Freakonomics, Bleakonomics. (Yes, that is my word. Yes, you are free to use it in your slide deck when you know corporate will shit themselves at the word “Enshittocene.”) But even those numbers require humans to interpret and narrate their meaning. It takes a human to, say, draw a likely-spurious linkage between the rising popularity of digital blue filters in Hollywood movies and the rising availability of Viagra and other drugs which turn human vision blue when taken more often than prescribed.

What computation does is assign meaning to numbers in themselves. At its base, this is ciphering: A=1, B=2, and so on. Coding and cryptography turn those values into phrases, and the phrases into functions. That’s why early computing could be done on paper or with punch-cards: their vocabulary was limited. One of my favourite ABC Movies of the Week, 1971’s Do Not Fold, Spindle, or Mutilate, is about those punch cards. You can find it on YouTube, probably. It’s based on a novel by Doris Miles Disney which is quite possibly the first book about catfishing — unless you count straight-up noir like Cornell Woolrich’s 1947 novel, Waltz into Darkness, which is set in the 1880s. But Do Not Fold, Spindle, or Mutilate is about how little information those cards could truly carry. After all, the cards don’t catch a serial killer. In the story, it takes a group of retired ladies to do that.

When we pair numbers with values, sign with referent, we re-inscribe meaning: history is written by the winners, and the winner is the top Google result. (That’s one reason why Judge Mehta’s ruling in the Google anti-trust case matters.) But it’s not like Aldous Huxley and Yevgeny Zamyatin didn’t see this coming a century ago. They understood that when you turn people into numbers, the next step is crunching those numbers. Brave New World, in which humans are classified by Greek letters more familiar to readers as algebraic variables, was published in 1932. In 1933, Dehomag — the German subsidiary of IBM and provider of Hollerith punch-card computing technology — granted their computing power for two censuses and data crawls by the new Nazi government. The same technology was made available to the American government, and made Japanese internment possible. In each country, the names, birthdates, locations, habits, loyalties, cultures, beliefs, sexualities, family histories of millions of people were suddenly crammed into a single number. Sometimes, the number was tattooed on an arm.

I wrote a departmental honours thesis on part of this process, when I was an undergrad. It was a year-long project. By its end, my classmates and I were all having the same nightmares. But it seeded a deep suspicion on my part of categorization, of ranking, of the ultimate context collapse of life into Likes. Because — as Umberto Eco tells us — one of the things fascism cannot stand is ambiguity.

“Ambiguity” comes from the Latin ambigere, a verb meaning “to dispute or be in doubt.” (The root of that word is amb, a word meaning “both sides of,” from whence we draw “amble,” or a leisurely walk, originally used to describe the gait of a horse who was not being whipped.) It describes the capacity to interpret things in multiple ways and disagree about those interpretations. But as Eco says, “For Ur-Fascism, disagreement is treason.” Ergo, much like early computing, fascism prefers for things to be one thing. A person must be a man or a woman, not both or neither. That woman must be Black or Indian, not both. She must be a mother or childless, not a step-mother. For me, the defining characteristic of fascism is this willful ignorance, this stubborn refusal to admit that there are other worlds than these, that we are bigger on the inside, that no one knows the whole story, that the card will never be large enough, that even words are paltry in the face of the ineffable.

Which is probably why I wrote a novel about a startup turning emotions into currency, via shady crypto shenanigans. And why that novel has so many murders–Miriam and I had to develop a (blood) flow chart for them all. Because, you see, the book is a murder mystery. It is about a future technology. It is about a startup that crash lands on a remote island on which there is only one black cube. It is about being a woman in tech and doing emotional labour. It’s about all those things, all at once. It’s a Swiss Army knife of a book. If one genre doesn’t cut deep enough, keep going. Try the corkscrew.

It’s called Glass Houses. It’s out next week. I very much hope you like it.

Glass Houses by Madeline Ashby

A group of employees and their CEO, celebrating the sale of their remarkable emotion-mapping-AI-algorithm, crash onto a not-quite-deserted tropical island.

Luckily, those who survived have found a beautiful, fully-stocked private palace, with all the latest technological updates (though one without connection to the outside world). The house, however, has more secrets than anyone might have guessed, and a much darker reason for having been built and left behind.

Kristen, the hyper-competent "chief emotional manager" (a position created by her eccentric, boyish billionaire boss, Sumter) is trying to keep her colleagues stable throughout this new challenge, but staying sane seems to be as much of a challenge as staying alive.

Being a woman in tech has always meant having to be smarter than anyone expects--and Kristen's knack for out-of-the-box problem-solving and quick thinking has gotten her to the top of her field. But will a killer instinct be enough to survive the island?

Member discussion