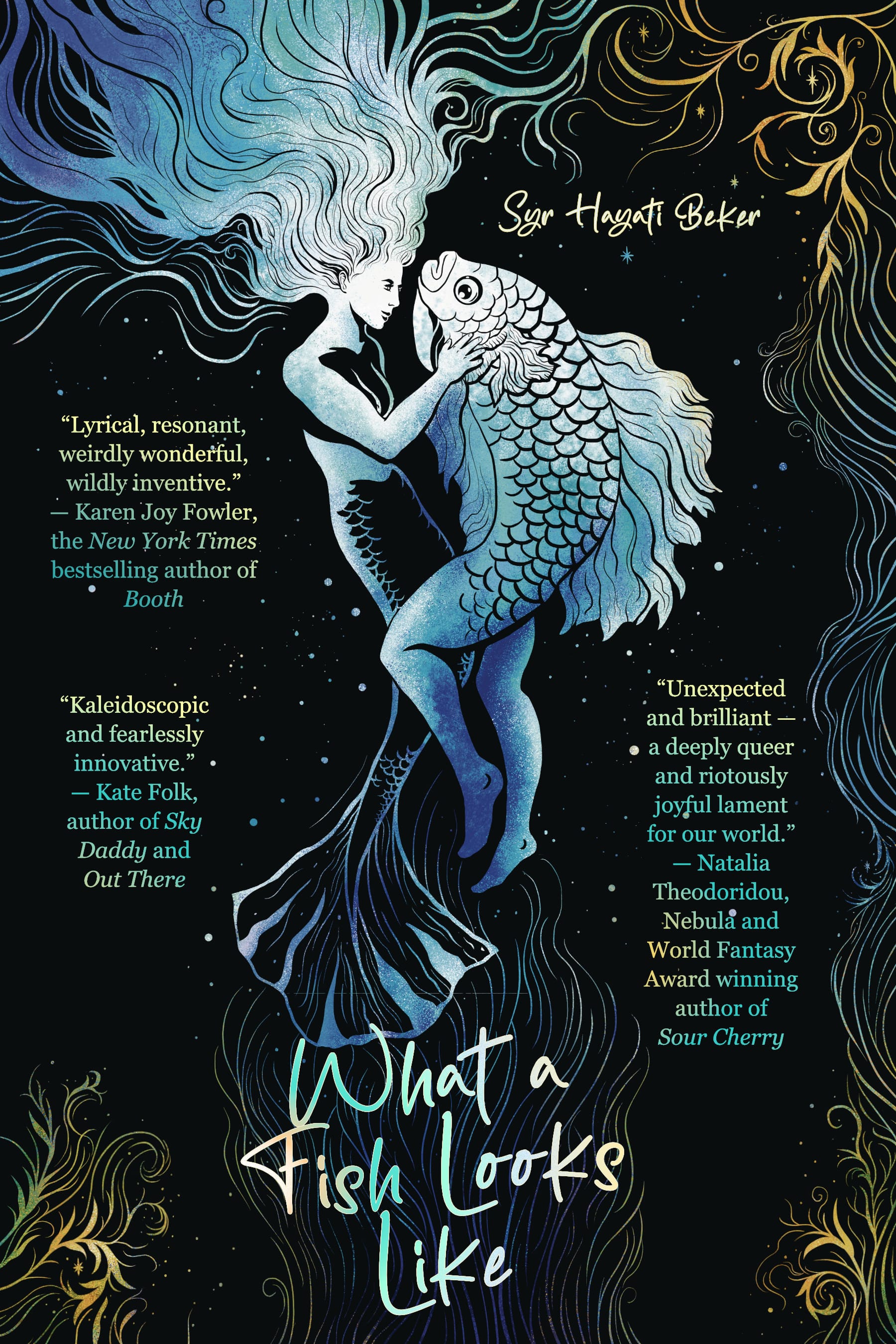

Exclusive Preview: What A Fish Looks Like

Hello friends! I’m so excited this week to share a preview of Syr Hayati Beker’s upcoming book, What A Fish Looks Like. Syr is a nonbinary Turkish-French-USian writer, immersive experience creator, and horror nerd in search of the queer love language of climate change. They are a graduate of Clarion West, Lambda’s Emerging Writers Fellowship, and have an MFA from SFSU. Syr is the co-founder of Queer Cat Productions performing arts company and The Escapery Collective. Their work appears in Foglifter, Joyland, Fairy Tale Review, F(r)iction, Michigan Quarterly Review, Spunk, Gigantic Sequins, Home is Where you Queer Your Heart (Foglifter Press, 2021), and in theaters, pirate ships, galleries, and queer bars near you. You can find them at SyrBeker.com, which is definitely not haunted.

Take us away, Syr!

Hello dear Stone Soup readers! I am so excited to get to be here and share a piece of my upcoming novella, What A Fish Looks Like. Thank you so much for having me! There’s a question I’d like to ask you: if a spaceship were to leave for a new habitable planet, would you get on it? Or would you take your chances down here with climate change and dwindling resources? Are You #Team Earth or #Team Ship?

What A Fish Looks Like imagines into this question. In a near-future ravaged by climate change, a community of queers is hanging on. In ten days, the very last spaceship is leaving for a new planet. 100 tickets have surfaced in the community.

In order to decide whether to get on the ship or stay, the messy queers in my book write to their friends and exes and friends-who-are-exes. They communicate in letters, flyers, postcards, notes scribbled on bar napkins, and margin notes written in an old book of fairy tales they pass around. And since everything is mutating, the stories in the fairy tale book are also mutating, because the stories we tell always look like us.

I really wanted the book to feel like you get to discover what happened from people’s letters and marginalia, there’s even a whole conversation written in graffiti, on a bathroom door. As you can imagine, this required A LOT of clever formatting, so I really have to thank my press, Stelliform, for taking that massive chance with me. Selena Middleton, Stelliform’s Editor in Chief, made the world of the book come to life. I can’t wait for people to see it!

Here is the beginning of one of the stories. This one is a reversed Beauty and the Beast. I gave it all my heartbreak and pettiness and yearning. Thank you so much for reading.

My Grandmother knit the Ocean.

Up all night with bargain-basement yarn, she watched her old nature shows and knitted fish. Silver fish, red fish, pink-and-orange-polka-dot-vodka fish. She finished each with a knot and prayer-spit and set it out to sea—which was her room in my mother’s house, painted blue. She knit fish like it was her job to fill the ocean, then she switched needles and made coral reef, filling the space with soft fractals, every color but white.

Habibti, she would say, a clownfish between her fingers, and another word I can’t remember that in my dreams brings all the fishes back to life.

My grandma died and then the ocean died. Both left blue rooms, one full, one empty.

#

And so last month, when you packed your boots, your flashlight, and a belt that was definitely mine into a box, there was no one to tell me, There are plenty of fish in the sea. Which is to say that after you said, “I don’t think this is working, I mean us, I mean this,” waving at the walls you insisted we paint yellow, I searched for words to keep me from unraveling and found none.

And because you never got to meet my grandmother, you probably think the reason I chose to ghost was because of you. Just to be clear: 1) there is absolutely nothing reckless about my decision; and 2) it had nothing to do with you.

Ghosting used to mean not answering someone’s calls and texts. Now it means you go to one of those special labs that have appeared in our cities. I went to the one near our coffee shop, the Expresso, where you first reached for my hand. In the past, ghosting would have meant avoiding the Expresso, our street, and all the places we used to go. Now, it’s the word we use to refer to the decision a small number of people have made. Ghosting means I open a reflective door and find myself in a sterile room where a woman with perfect bangs hands me a form and a pen, and tells me to take my time with the answers.

I sit down next to a guy about my age, with lighter brown skin and bleached spiky hair. One of his sneakers squeaks and his pants are too low. Evidence: three hairs emerging like dandelions from the front of his concrete-gray jeans.

Now, when you tell people I ghosted, they’ll picture me here, filling out a form in a lab close to our apartment, initials on every page, while this boy, Dandelion, tries to get a word in.

“Don’t worry about it too much,” he says, “I don’t think they actually read it.” He laughs a bit too long.

The ghosting form begins with a space for my legal name and the official name of the procedure—Voluntary DNA Surrogacy—both of which are obsolete. I skip through two pages of explanations and cautions, to the part of the form that wants me to think about what I would be giving up.

Do you accept the terms and conditions of the procedure?

[“Do you think we’ll ever see a dolphin again?” you asked at the Expresso, a million years ago, and I was going to answer but you paused, shifted, and leaned against me. I smiled and gave you my drink to finish, and then the electricity went out like it does all the time in fire season, and we went back to my apartment, and you knocked over a glass, and you laughed and apologized because back then you didn’t know everything I had was yours.]

Yes, I write. Initials.

Do you understand that the procedure is permanent and irreversible?

[The first people to ghost were told the infusion would be temporary, that they would only be lending their body for a short amount of time. A year. Or five. Ten at the most.]

Yes. I understand that the procedure is permanent, which is different than “forever,” which means nothing at all.

Sex:

[“Clownfish,” I said. “Began as males and became females. Kobudai did the opposite. Gobies switched all the time. Now they’re gone.” “We’re still here,” you said, and smiled, and I clung hard to that “we.”]

F, is the box I check, options being limited.

Emergency Contact:

[“You know what your problem is?” you said, tired of all the nights I spent at work, at the lab, listening to ocean water instead of with you, “Your problem is…”]

I hesitate, and finally write your name.

Species Preference:

I pause over this last question. Dandelion watches me pause.

I’d prefer to be invulnerable. I want claws and jaws and height. I want there to be a box with my name on it, and when I check it, I want the power grid to surge and for every room to be flooded with light.

[“…your problem is you don’t know when to let go.”]

Species Preference: I write None. No preference.

And I stand up to take the form to the desk before I can change my mind, pen clattering to the floor.

What are the stories we need to survive?

In ten days, the last spaceship is leaving for a new planet. Some of us will stay on Earth. How do we decide?

#TeamEarth. Once upon a time, the oceans were full of fish and the forests dark with brambles. Seb read about it in a book of fairy tales, and memory means hope.

#TeamShip. Adaptation means knowing when to walk away. Jay is ready. So their ex, Seb, shows up on the dance floor, T-minus-10. What’s the harm in one last dance?

What if the stories themselves are evolving?

Told in margin notes, posters, letters scrawled on napkins, and six retellings of classic fairy tales, What A Fish Looks Like gathers the stories of a queer community co-creating one another through the strange landscapes of climate change, wondering who is going to love us when there are not, in fact, plenty of fish in the sea.

And now this book belongs to you.

What A Fish Looks Like will be out in the world September 4th. You can preorder a copy here, and if you love books that expand the conversation around climate change, eg, with queerness and ecohorror and indigenous futurism, and dragons and so much else, you can check out other books by Stelliform Press here. Every one of them is a banger. And if you want to tell me if you’re #Team Earth or #Team Ship, I always want to know! You can scribble me a note at SyrBeker.com. Thank you so much for letting me visit!

Thank you so much for sharing this with us, Syr! I can’t wait for this one to be out in the world.

In the meantime, dear readers: Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

—Gailey

Member discussion