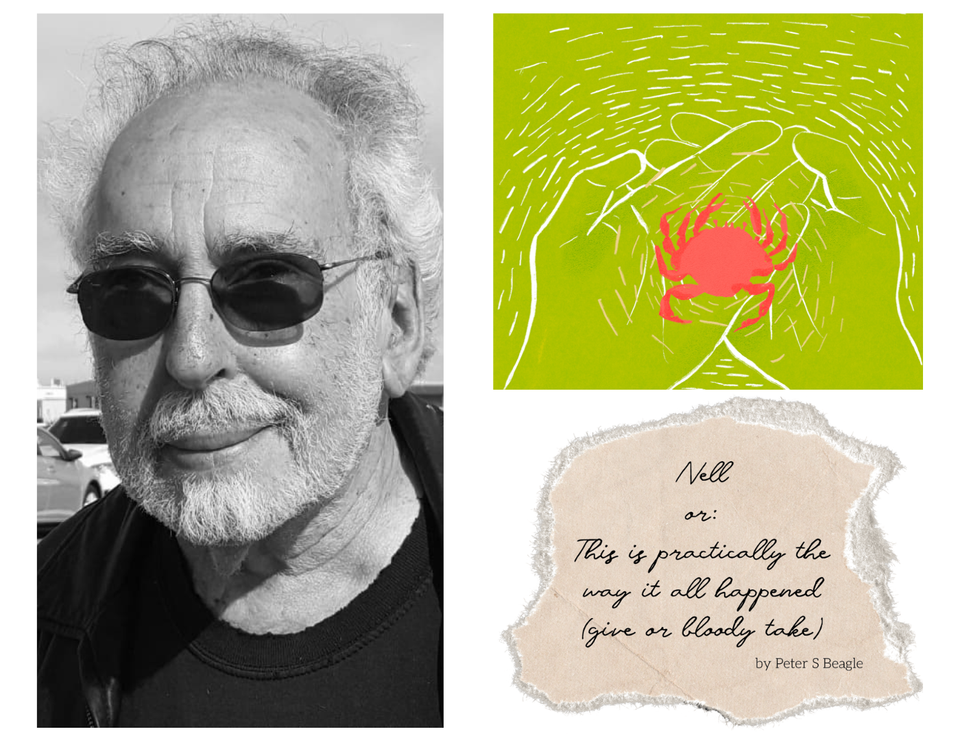

Nell, or: This Is Practically The Way It All Happened (give or bloody take)

Peter S. Beagle – Noted author and screenwriter Peter Beagle is a recipient of the prestigious Hugo, Nebula, Locus, and Mythopoeic Awards, and a World Fantasy and Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America 2018 Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master, among other literary achievements. He has given generations of readers the magic of unicorns, haunted cemeteries, lascivious trees and disgruntled gods. A prolific author, his best-known work is The Last Unicorn, a fantasy novel, which Locus Magazine subscribers voted the number five “All-Time Best Fantasy Novel” in 1987.

This is a true story. This actually happened.

I mean, to one degree or another, all my stories are true. The one about a unicorn, or Lila the Werewolf – well, no, that one really did happen – or, say, the stories having to do with the strange wine, the man who becomes French by degrees, or even the two old ladies who are rescued from a demon-haunted aquarium by a mermaid and a deep-sea diver… these stories and others are as perfectly true as truth ever gets.

Truth is not what you think it is. I can honestly say this, at the age of eighty-five, because this is all that I have ever done. I have written a dozen books, sold stories both to movies and magazines, invented scripts for actors, and talked my way into meetings with men I wouldn’t ever allow my daughters to date. I rewrote dialogue for actors whom I knew couldn’t handle the lines I’d first written, and I learned equally how proper actors can bring an echo of loss and sorrow and dread to phrases that you never thought to put there.

And when all else failed, I shoplifted. You do what you have to do, and so did I.

So. I have married three times, to three remarkably different women. One of them wanted to marry me for sensible reasons, having three different children, all of whom I adopted. In the Bronx of my childhood, you didn’t walk away from children, for good or ill. The second woman, who was by far the finest writer I ever knew, I loved and admired as best I knew how, knowing that she loved me in just the same imperfect hiccupy way. The third woman… well, she did the very best she could against impossible odds. She never had a bloody chance.

Things and events blur when you’re old, but never quite in the way that you expect them to blur. For instance, I know exactly where I was when I married my first wife – in that dear, impossible shack deep in the redwood hills of Santa Cruz, California, with the dog and the pigeon who had loved each other since before we moved there. What I can’t remember in more than a shadow is who I was back then, except that I wrote almost every day in a half-demolished shed down the hill from the shack we moved into; that I read to my three brand-new children every night, just as I’d been raised to do; and that I sang their own particular chosen songs to them every night, as specially requested. Because that I’ve always known how to do, from my own earliest childhood. That kind of attention, I know how to pay.

The only other thing I could do was play the guitar and sing. I’d learned guitar at the age of eleven, in practical preparation for life as a cowboy on the western plains. And then, in college, by purest possible chance, I heard a very strange man named Georges Brassens on a record, singing a song called “J’ai Rendezvous Avec Vous.” He had a deep, rough Midi voice (not that I’d have recognized the accent, since I didn’t speak any French at all back then). He often sounded this close to going flat – but he never did – and what the hell was that thing he just did, changing keys that sneakily on the guitar? Whatever he just did, I want to do that!

In Santa Cruz, I got a gig singing at a French restaurant on weekends. The pay was twenty-five dollars a night, plus whatever tips there might be – and, whatever else, a splendid dinner after I was done for the evening. Twenty-five went a lot further in those days than it does today. Now and then I’d even be invited to play at some special gig in Santa Cruz or Monterey. I can say truly that I had absolutely no fantasies about being a best-selling author. I might be stuck with being a fantasist, but I definitely couldn’t afford to live there.

So there we are. I was 37 or 38 years old, somewhere in there. I wrote and I sang, and I fed increasingly assorted animals – it’s a long story, don’t ask – and every evening I read to the children before bedtime. And I can say with absolute honesty that I never thought much, one way or the other, about being happy or unhappy. I was I was doing the work I knew I had been born to do, and taking proper care of a family as well, just as my parents had done. What happy? as we say in the Bronx. Go complain.

And then, literally between one minute and the next, that fucking Nell from Louisiana walked into my life, and everything went gloriously to hell. For bloody ever.

Not that I knew it like that, of course not. God’s sense of humor – as has been pointed out by ever so many Certified Thinkers through the millennia – verges on the diabolical.

I was married, with children, and truly not looking for trouble; just as long as I got my work done and the kids fed, who had time for trouble? I was just going to a surprise birthday party in Palo Alto for a magazine publisher I’d once sold a piece to. Stop in, have a drink… might even be home before the oldest girl’s asleep. Being suddenly, shockingly exploded into fatherhood, I still took such matters remarkably seriously.

The bloody woman opened the damn door. It wasn’t even her damn house, what can I tell you? She just opened to my knock, smiled utterly and said, “Hello – I’m Jenella DuRousseau. Help me put up the decorations."

That is exactly what she said, as she handed me a hammer and some nails. Word for fucking word. I’ve played those words back at night more times than I’m ever going to tell you or anyone.

Me? Oh, I remember my own opening lines just as clearly, just as precisely. I said, “Oh. Right. I can do that.”

It’s been forty-seven years, and I can’t honestly say that she was the most beautiful woman I ever saw in my life. The pure truth is that the world’s full of beautiful women, full to bursting, if you want to know. I’m old enough – oh, thank every single one of all the blessed gods – to know that I can walk around my block, when my legs are up to it, and pass more breathtakingly beautiful women than any old man had a right to see in a lifetime. Were there always this many, when I was thirteen years old on Gunhill Road in the Bronx, young and too romantic even to know that I was living in Paradise just walking to school or shopping for my mother? Did I even guess? Did I have so much as a clue?

When Ms. Jenella DuRousseau saw me still gaping at her beautiful light-brown face, she smiled again and said, “Oh – I’m Creole.”

And so she was. I’d never met a Creole person before. But the magic of the single word suited me, and the sound of her voice – neither comic-strip Daisy Mae-southern, nor remotely French or Canadian – left me staring and nodding, and mumbling something that sounded like, “Yes… of course, you are.” And if I didn’t actually mumble that, what I meant precisely to mumble, was “Of course, you are. What kept you?”

I got home at a perfectly decent hour that night, told my wife that I’d done the gentlemanly thing by my former editor, and even read a story to my eldest daughter, who should really have been in bed by then. And before I went to bed myself, I wrote a letter to Jenella DuRousseau. It didn’t have more than a few lines – I can’t really recall any part of it but my address and my phone number. No more than that, surely.

What matters is that my letter crossed her letter in the mail. Address, phone number… nothing more that night. I’m quite clear on that, as long as it’s been.

To be fair, if that should possibly matter, it wasn’t all that long before my first wife and I separated quite amicably, nobody really ever looking back. It was well past time: the girls were both grown and already off to their futures, the older one married and the younger living and working in Europe. My son was still living at home with me, but his mother was living only a couple of miles down the road, as amicably as makes no matter. For myself, I was home almost every night, whether my son was or not, cooking dinner, and still reading aloud every evening after homework. On the occasions when a couple of his friends stayed the evening or the night, I read to them all as requested. I missed it when he finally decided that he was too old for bedtime stories. I still do miss it, you want to know. At my age.

With both of us officially divorced, Nell and I saw each other when we chose, though we were astonishingly cautious about it. Which is remarkable, when I think about it. We were both young, both raising children essentially alone (Nell’s own 10-year-old son, lived with her), with no attachments or obligations anywhere to be seen. Yet, for all the dizzying bewilderment of our meeting (who are you, and where have you bloody been?), we remained strangely wary, going out to movies and theatre as primly and cautiously as you could imagine. Nothing at all untoward happened until the evening I brought Nell to a restaurant in Monterey to introduce her to my younger daughter.

I remember that particular evening especially well, because that’s the one where Nell and I enjoyed a properly friendly dinner, said an equally courteous goodbye to my daughter, got into my old car, looked briefly and silently at each other, and raced to get straight back to Nell’s house as fast as we could. It was unspoken, mutual and overwhelming; and I think now, in hindsight, that it needed to take a very long time to throw our hats over the windmill together. Because neither of us had the least notion of where or when, or even if those hats would ever come back down.

Speaking strictly for myself, I never did know. The true wonder is just how long it took me to realize that I simply, purely didn’t care. What can I tell you? You can’t get much slower on the pickup than I am.

In my own defense, I do have to state that when I really, really know something, I know it finally and thoroughly for good forever. Which can create its own problems, but never bloody mind. As I’ve already told you, it went on from that party in Palo Alto through three wives, various lands, and assorted lovers on all sides of the known world. For my part, at least, I was as earnestly and quite consciously trying to get Nell out of my mind, heart and kishkes as I’d ever tried to get a single goddamn sentence or story to come out fucking right. Deeply and almost frighteningly as I’d loved being with her, I was – so at least I imagined – very nearly relieved when she told that me she’d been offered a job teaching somewhere in… where? Brazil? You are kidding, yes?

Well, no, she wasn’t. Like that line by A.A. Milne, or Saki, or some other Brit, “She was a very good cook, as cooks go – and, as cooks go, she went." Alone, and with absolutely no idea of what waited on the far side of all she knew… she damn well went. Nell was like that.

Could I have stopped her? Right then? If I’d firmly, bravely, said “Don’t go. Stay with me! Whatever bloody happens, just stay with me!” Would the earth have stopped revolving? Would the law of gravity have been canceled? Would bells and gongs and John Philip Sousa all gone off at once, the way it used to happen when you scored the highest Grand Slam at my beloved shooting gallery on Forty-fifth Street? (Happened to me twice, that did, and I still remember both times.)

Yes, well. It’s a peculiarly pointless question, obviously, because not only didn’t I have the courage to say that, I was genuinely relieved. No… genuinely isn’t a good enough word, for all its undoubted virtues. Immensely relieved will do, though even that isn’t the exact word either. Thoughtlessly might do as well as any. With Nell safely out of the country and out of my hair, I wouldn’t have to think about her anymore – not in that way, which was unquestionably best. In between the assorted marriages, there were other women coming and going, which was fine with me, because once they were gone, I could get back to work without thinking about them for a single disturbing moment, because that is what I do. Always. I swear. The rest of it is just trying to do the work better this time.

Except, as it turned out, the rest of it was actually me calling the creaky, spluttery phone in Brazil within two days of her departure, trying frantically to make sure that the bloody damned impossible woman was safe and well, wherever the flipping hell she might be. Brazilians speak Portuguese, which barely nods in the general direction of the New York Spanish I speak. Fortunately, her thrice- blessed landlady spoke just enough English that we practically became sorority sisters on the phone. It took me awhile to persuade her that I was a respectable young man, who could safely be permitted to talk with her new boarder.

I didn’t see Nell again for two years. We wrote a lot of letters, and we talked whenever I could make my drugstore cellphone connect to Brazil – or to Africa, eventually, because she’d met a French oil engineer on a flight to Europe, and married him, because why not? He had plenty of money and knew how to show her a good time. I never did meet him, but my Nell had been poor quite long enough, and fair’s bloody fair, after all. I’d had my damn chance, and had the good sense to wave as it went by.

But it never ended, no matter whom either of us was married to or involved with. I never did stop writing letters, and Nell never stopped calling at ridiculous, dangerous hours. Thirty-five bloody years. Thirty-five years, and neither one of us could ever leave the other the hell alone. Lord, these days even a child knows to say, “Jeez, just get a room, all right?

Which we did, of course, all over the world. I’d get invited to speak or read from my work in England, or in Spain, France, Holland… Yugoslavia, Slovenia, Greece… One way or another, Nell would meet me, either at the local airport or the hotel where I’d be stashed. I learned never to ask how she got there, nor how much time we’d have together, nor when the next time would possibly be. Grab what you can get, savor it, and be grateful ever after. “Lick up the honey, stranger, and ask no questions,” as my old hero Harry Flashman is wisely told. So I did. So I still do, and feel lucky still in what I do have. Because I might so easily have missed it all.

She came back to America three times in those thirty-five years. As far as I ever wanted to know, anyway. I add that part, because while Nell never once lied to me, what I chose not to know was entirely my own business. I recall that she came to the Bay Area on a short visit, to see her son. I met her at the San Francisco airport that time, and we had a nice dinner and we stared at each other for a very long time. Then I drove her back to her son’s house, where we parked at the curb and she grabbed my ears and kissed me so fiercely that my head rang all the way home. And that was that for the next year or two.

There was the time when she came to some fancy resort in Montana – I think with her husband, but it could have just as easily have been some other man. Nell did always love fancy resorts.

And then there was the time when she came to stay with me in the Watsonville house, and was there for almost a week. I play that one back in my head a lot. She was studying for some degree or other in Arizona, as I remember it, and what she was doing in my bed in California I couldn’t tell you.

Nor can I tell you much about that week. A couple of dear friends and their small son were living with me at the time – they needed a safe home, and I suppose I still needed children – but Nell spent most of her time in my bedroom, working assiduously on that degree; while I was staying out of her way down in the barn, working myself on one book or another, because that’s what I do, whether or not my one love is with me. She was as proper and gracious a guest as she could have been, showing up courteously for meals before she went back to studying. I can only remember her coming decorously down to visit me in the barn once or twice during that week. Nell was a Louisiana lady, the only one I’ve ever known, and she had no intention of embarrassing my friends. Whatever I might think about it.

I remember two things about that brief time with her, so long ago. I remember that once, with the bedroom door closed and all deeply, wondrously quiet, we were actually in bed when I suddenly realized that I hadn’t fed any of the assorted animals who depended on me to care for them at night. I apologized to Nell, threw on my father’s ragged old bathrobe – which I still wear – and hurried off to cut up some chunks of fruit for Lucy Brown, the ancient kinkajou, and make sure there were enough mealworms for the bushbabies, who tended to wake up hungry. Then I went back to Nell, who was still exactly as I had left her, kneeling with her eyes glowing and deeply amused. I remember her whispering, “All well in the wild, then? My turn now?” To her last day, I never truly learned what would make her laugh in that special way.

The last night, before she left, we spent in that uphill Berkeley hotel where I’ll never stay again. More than anything else - more even than the breathstopping miracle of Nell standing naked by the window, laughing on the phone to her best friend in London while she never stopped looking at me – I’ll remember until I die the silly wonder of her turning to me while we waited for our table in the dining room, commanding her own special Dolly Parton song, the one I always sang to her in the car.

"Oh, sometimes I go waking through fields where we walked

long ago, in the sweet used-to-be,

and flowers still grow, but they don't smell as sweet

as they did when you picked them for me..."

That was Nell’s song. She loved others, surely, during thirty-five years of our singing together in my car, but that was the song she always asked for, even when we were far away from each other. She’d call in the deepest night to hear that bloody, beloved song. I’ve never sung it to anyone else, even my children.

She never told me she was dying. I knew she’d been treated brutally for cancer, receiving both daily radiation treatments and assorted courses of medication. Her brother came to France on three occasions to stay with her, while I called her every day to be reassured that she was doing just fine, thinking about leaving the hospital in a couple of days. I believed her because I wanted desperately to believe her; and, as well, because I really had known her more than once to slip the clutches of the universe and walk away to me with me one more time. Both I – and, by God, the universe itself – had learned that Nell DuRousseau always did exactly what she wanted.

Until the very last time, the very last phone call, when she told me firmly, “Don’t come. I look terrible.”

And because I am not a total idiot, despite a lifetime of recorded evidence to the contrary, I said, “Shut up, woman. I’ll be there tomorrow.”

I was, too. Somehow I caught a direct flight from San Francisco to Paris, and then a train from the airport to the Midi hospital her brother had brought her back to one last time. Her son met us, and we drove like mad to the hospital – which, of course, had long been closed to visitors by the time we finally got there. “Come back tomorrow, early, a tres bonne heure!” we were assured. “She will still be here, je te l’assure!” I’m reasonably sure they believed it themselves.

But she died in the night. I don’t know how long I stayed with her, stroking her hair and kissing her cold mouth, telling her over and over how beautiful she was. Because she was deeply vain, with that particular sort of blithely serene vanity that so often covers the deepest kind of fear. Perhaps because I could never be sure when I’d see her again, every time we met was always, always that first dazed time. Who the hell are you?

As it still is, almost a dozen years later, when I wake and see that face across the room, smiling from her photo on my desk. I usually just croak, “Hey, you. Hello, you.” I tell her what I need to do today, and I reassure her that she’ll be with me wherever I have to go today. I don’t leave town without her, for any reason, and she’s still the last voice I talk to before I fall asleep. And in the end, I say the same thing, every impossible night, as the memory grows slowly more distant while her soft, not-quite-singing Creole voice remains as impossibly clear as it ever was, from the moment she opened the door and everything changed.

“Goodnight, love. I’ll see you in the morning.”

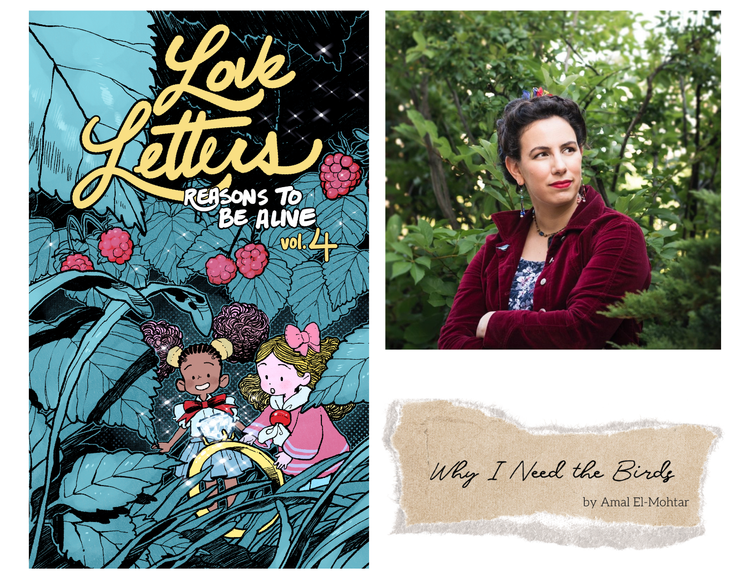

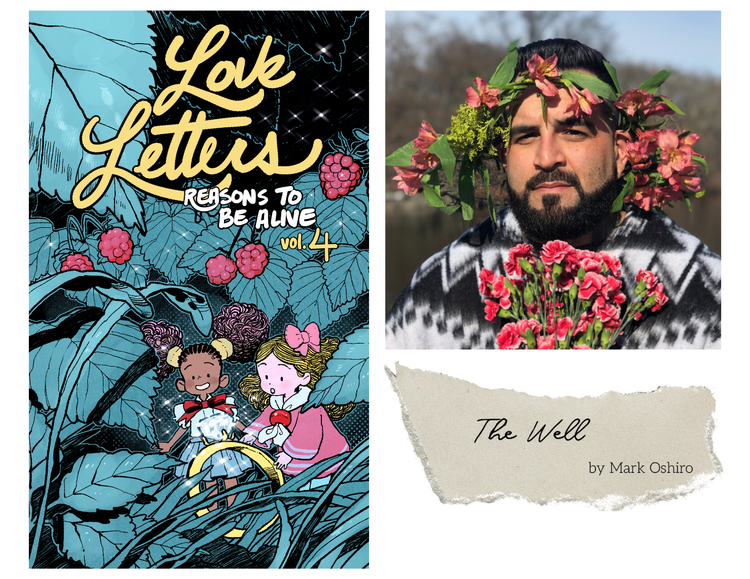

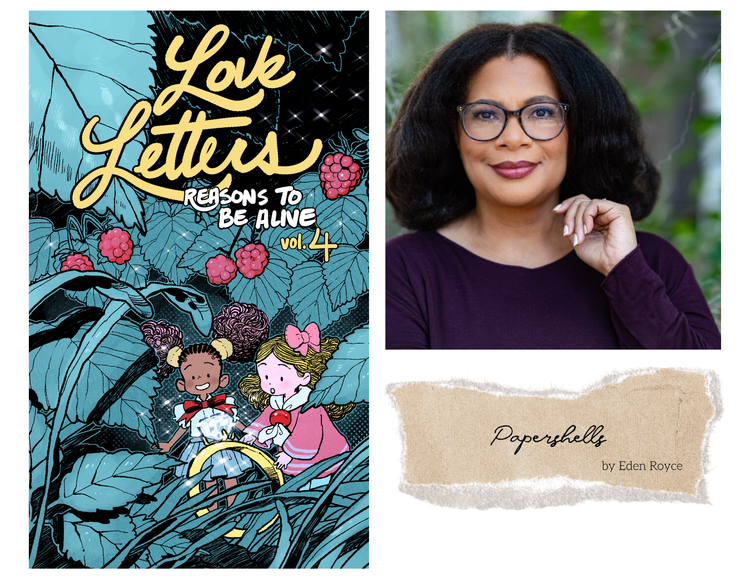

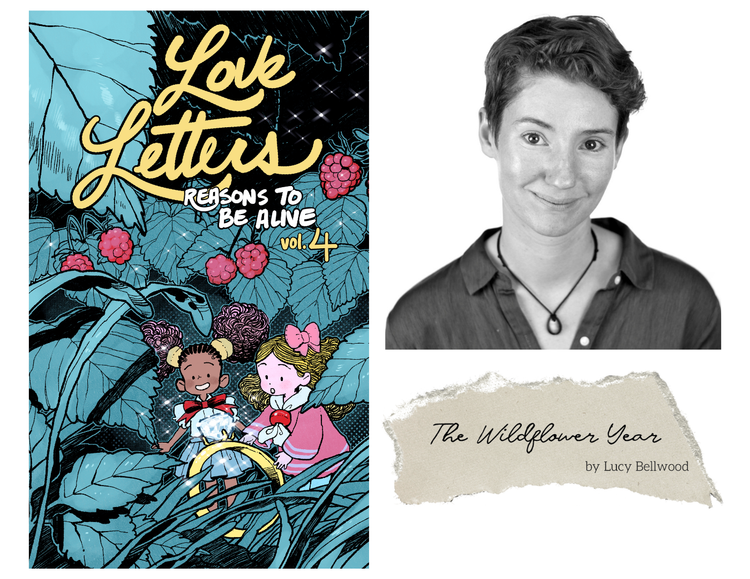

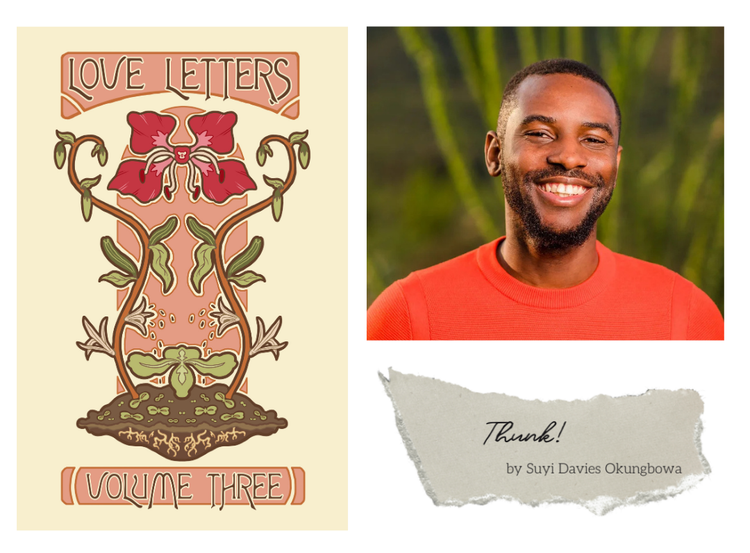

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion