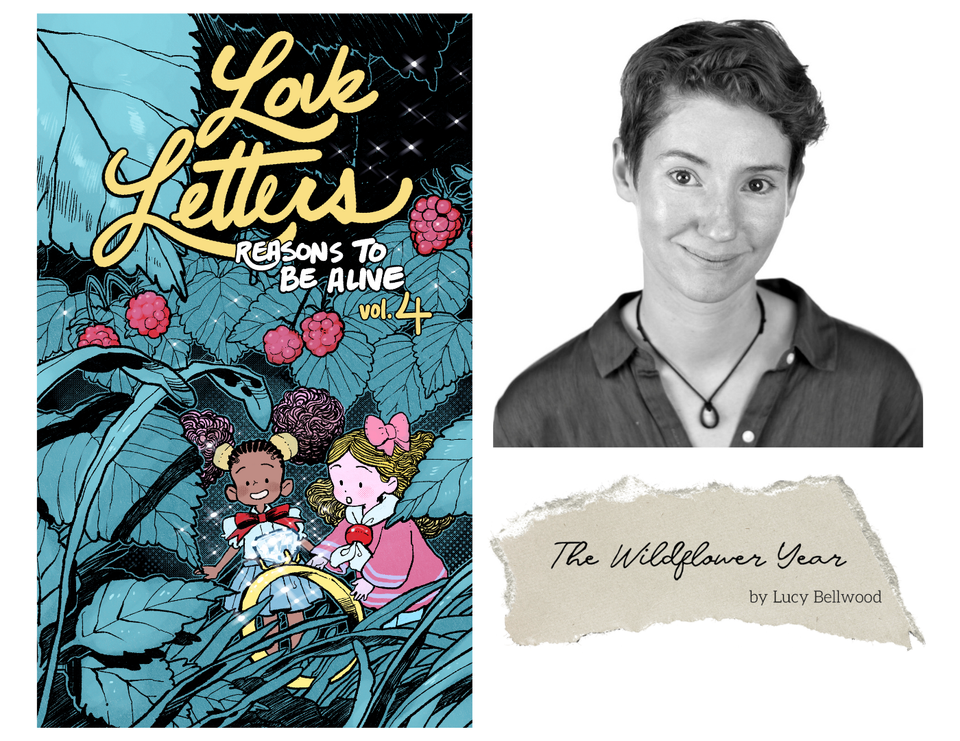

The Wildflower Year

Lucy Bellwood (she/her) is an Adventure Cartoonist and former caregiver based in Ojai, California. Her comics projects cover a range of expeditions, including rafting trips through the Grand Canyon, cutting-edge oceanography in the Pacific, and a voyage aboard the last wooden whaling ship in the world. She is the author of Baggywrinkles: a Lubber’s Guide to Life at Sea, a collection of stories from her time as a tall ship sailor, and 100 Demon Dialogues, a helpful, humorous guide to living with Imposter Syndrome.

I once loved a man who gathered seeds.

His pockets were always full of twisted paper packets, each laden with kernels of life. He’d collect them in parking lots and public paths, sidewalk gardens and highway medians, bringing each one home to germinate in brightly-lit trays in the cupboard under his sink. His passion for growth grounded me at a time when everything else in my life seemed to be falling apart.

I’d recently become a caregiver at thirty-two. My father was already five years into a vascular dementia diagnosis. Driven by a sudden downturn in his condition, I moved home to the valley that raised me. Physical therapy routines and medication schedules replaced my former life as a traveling cartoonist. I knew I needed to be there—wanted to be there—but the move still came at a price.

Home was grief, but it was also chaparral and lizard tails and the scent of orange blossom in the spring. A landscape I’d missed in my bones. I thought, perhaps, this seed-gathering man and I could grow something in that complex soil.

It was autumn when things fell apart between us, dissolving like the mist that was just starting to linger on the valley floor in the mornings. Not knowing what else to do, I bought a jar of native wildflower seeds and wrapped myself in research, stealing moments from caregiving to determine optimal sun exposure and watering schedules.

I tried to plan for perfection, but all it left me with was paralysis.

At the time, I approached my father’s care as an act of desperate preservation. Long before his illness, I had dreaded his loss. He’d turned fifty the week I was born, the same week he wrote me the first of the hundreds of letters and postcards I’d receive from him throughout my life. “Darling Lucy, How extraordinary to be writing my first card to my DAUGHTER!” I was six days old, but he was already addressing me like a fellow adult. He never talked down to me—or any other young person for that matter. Heartbreaking, then, to have to coach him through the most basic of tasks: Putting on shoes, lifting a cup to his mouth.

I’d always carried an awareness of his age (wrapped, in later years, around impotent fury at his unwillingness to care for himself). The more affection and support he gave me, the greater my fear. Who would I be without him? How could I survive the loss of someone so eccentric and creative and kind? My anxiety grew in proportion to my love. Close to him again after years of independence, I snatched audio recordings of his voice and scribbled notes about his habits; Aesop’s frantic ant gathering grain for the winter that was bound to come.

But the work that came to define my days wore even that anxiety smooth. Counting pills, washing soiled sheets, and tending wounds returned me, again and again, to the reality of the present. To how little I could control. To mortality.

Eventually, I gave up, scattering the jar of seeds indiscriminately around the yard.

It happens all at once.

Caregiving has many rhythms: The little loops that circle back on themselves day after day, the broader downward stair step of decline, the sudden swan dives into panic during a midnight fall, or the rush of hope when, just for a moment, selfhood returns.

The carpet of green that greets me that morning in December is urgent, irrepressible. The fresh seedlings are uniform at a distance, but distinct as fingerprints up close. Frilled edges, solid lobes, delicate fronds. I’m on my knees, palms pressed to the earth, whispering hello.

In the grinding monotony of grief, here is something new; something I have played a small part in cultivating.

I learn to tell them apart long before the flowering season: Arroyo lupine, Tidy Tips, Chinese Houses, Baby Blue Eyes, California poppies, Elegant clarkia. I gather names as quickly as my father loses them. Part of me thinks it is frivolous to grow flowers at a time like this, but I don’t care. I am trying to wrestle joy from this year.

Every morning I scurry out with my tea to marvel at their progress. I whoop when the first bright bloom opens in March. I wail when gophers gnaw a stem off at the root.

My family has always celebrated with fresh flowers from the garden. For years, it was my father who gathered them. He had a flair for the dramatic, an eye for color and contrast. He’d disappear into the garden early in the morning—on my birthday, at Easter, before Mother’s Day—and return with armfuls of blossoms.

Out of everything I plant, it is the clarkia that thrives the most. Its stalks reach my waist, leaning drunkenly into one another as they branch toward the sky. The carefully-spaced buds bloom for months—well into July. And what blooms! Swooping red and white stamens crowned with four lanceolate petals, all salmon pink or royal purple or white.

I find a stand in the wild while hiking a childhood trail (the one with the tiny sandstone cave two and a half miles in). They’re massed on the hillside—a patch high as my shoulders and twenty feet across. It thrills me to see them like this. I realize that if I allow them to continue their seasonal dance, they’ll replicate the steps in my own backyard.

When the clarkia at home begins to wither during the first heatwave of August, I feel a familiar sting of disappointment and loss. But the flowers leave grooved green capsules arrayed along the stem in their wake. In the weeks that follow, these tiny furred cucumbers grow dry and brittle and start to split; a flowering of their own. One by one, their ends peel back, creating a series of fluted goblets. In September, I upend one in my palm. It showers me with dark pinpricks of possibility, and something inside me stirs.

I tip handfuls of seed into my pockets and wait for the rain.

It is winter again. My father is still alive.

When the shoots come up for a second year, I’m shocked at their profusion. Never mind that I didn’t water assiduously or amend the soil. There are seedlings in places I never thought to plant—silken stands of red Mikado poppies and spiraling vetch that have germinated on their own. They want to be here. Their thriving rests on delicate movements of sun, rain, and soil. Nothing they do is wasted.

I realize I am not dancing this dance alone.

Wildflowers are food. They form a living carpet of sustenance for hundreds of local species. Butterflies and bees, hummingbirds and moths, mice and squirrels all rely on nectar, stems, and seeds. So the gophers eviscerated the lupins? Very well, I’m glad to have fed them for a spring. The butterfly larvae gnawed the baby blue eyes to the ground? I hope they were delicious.

Caring for my father has become less and less about fighting the inevitable and more about communicating in a language he can still understand. I stroke the warm expanse of his forehead every morning. I tuck the clarkia into a bouquet when he turns eighty-five in July. I can’t suppress the gifts he gave me—my ease with strangers or my reader’s magpie mind. His love is native to me.

There is nothing frivolous about growing flowers. It is necessary work. And necessary work has room for both wonder and loss, gratitude and grief. The lesson of the wildflower year is seeing the beauty beyond the bloom; coming to love the dried and splitting seedpod as much as the first green shoot. Learning that even in the scorch of late summer, when all seems dusty and barren, the resting sparks of our delight lie waiting in the soil.

These days I gather seeds in the mornings, before he wakes and I begin the day’s work of changing and feeding and bathing him. I pluck the furred capsules one by one, twirl them between the pads of my fingers, and catch the shower of grain. I fold them into paper packets, tuck them into envelopes, and mail them to friends across the state.

They ripple and travel. Seed to seed, bloom to bloom. A web wider than I can possibly imagine.

It feels like immortality.

It feels like love.

My dad, Peter Longden Bellwood, died on July 13th, 2025—almost exactly a year after I started writing this piece. The experience of his death is a different essay, one I hope to write in time, but I want you to know that it was devastating and beautiful, and that it is also part of this story, and that I loved him more than I can possibly say.

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion