Dark was the Night

Bo Bolander’s (she/they) fiction has won the Nebula & Locus Awards and been short-listed for the Hugo, Shirley Jackson, Sturgeon, World Fantasy, and British Fantasy Awards. Her work has been featured in Lightspeed, Uncanny, Tor.com, and the New York Times, among other venues. She currently resides in New York City.

Like many fairy tales, this one starts with a wicked stepmother.

Once upon a time, there was a little boy born to a poor farmer and his wife. The boy's mother loved him very much, and when he was five, she gave him a magical instrument: a cigar box cleverly strung and shaped into a kind of makeshift guitar. It was his most prized possession, even more so after his mother suddenly passed away and his father remarried. How this affected the little boy's life nobody living can say, but what is known is that around this time he decided he wanted to be a preacher when he grew up, a man with a direct line to God's ear if any soul on earth had one.

One night, so the story goes, the father caught his new wife in the arms of another man. He beat her terribly and in retaliation she grabbed the nearest thing to hand, which happened to be a pan of lye, and threw it at him. It missed the father but splashed into the face and eyes of the son, burning him and robbing him of his sight. For the rest of his days, he would travel through darkness, navigating by sound and touch alone.

They say losing one sense sometimes sharpens others. The hearing grows keener. The fingers may grow more sensitive. What frequencies did that little boy's ears pick up, drifting in the sudden vacuum left by his stepmother's screams and the doctor's pronouncements and the memory of the last light he ever saw?

꘏

Voyager 2 was hurled into space on August 20, 1977, 80 years after the little boy's birth and 32 years after his physical body gave up the ghost. It reached the interstellar medium on November 5, 2018, a couple months short of his 122nd birthday, moving at approximately 34,320 miles per hour. If it does not fly into a star / cross paths with a black hole / drift noiselessly into a comet's path with the awful inexorable spin of lye arcing from a swung skillet, then there's nothing that says it and its twin cannot continue their journeys indefinitely. When all our bones are dust and that dust is a line of radioactive sediment in a stratigraphic layer halfway down some vast canyon wall carved by a wind more at home on Mars than present-day Earth, the Voyager probes will still be going strong. When our Sun grows as soft and red and overgrown as a forgotten orange rotting on the bough—unpicked because there are no hands left to grab it—when Earth is absorbed/consumed/melted to plasma, even the bone dust in the canyon cut vaporized—somewhere out there, silent and unstoppable, there will still be some record of who we were and the dreams that occasionally gestated in the darkness behind our eyes.

꘏

The little boy is out there, too. Because one mother gave him a cigar box guitar and the other took his sight, Willie Johnson is now as close to immortal as it is possible for a human being to be. With the exception of the handful of other artists and voices included on the golden records of the Voyager spacecrafts, no-one else who has ever lived–no emperor, no despot, no tech guru or cult leader or lover or poet chiseled into marble–can make that claim. Maybe some day some preening billionaire will pay a small army of privatized scientists enough to change all that, but as of this writing that is blessedly not the case.

For the boy grew into a man, you see, and as he had wished he earned a living preaching the Lord's gospel to anyone who would listen. He was aided in this mission by two talents: a fantastic voice, and an almost supernatural way with the bottleneck slide. By placing a glass slipper on his finger, Willie Johnson could make a guitar emit sounds so wailing midnight locomotive lonesome people walking by his street-preacher's pulpit would stop dead in their tracks. Even today folks are baffled by how the hell he got that sound. (Personally I think it was that he was really goddamned talented but I'm no musical scholar.)

Blind Willie Johnson wouldn't have called his compositions the blues. The blues was music by and for sinners, mired in juke joint purgatories. Every song he ever wrote was religious, including the one included on the Voyager probes, "Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground."

There are no discernible lyrics. The only vocals are a singsong moan that wavers on a literal knife's edge (he used a penknife as a slide on this one) between desolation and hope. The guitar quavers through darkness unceasing but never stops clawing a way forward even when the waves close over its head and the mouth of the black hole gapes inescapable. It's a bad 4 AM with only the faded Polaroid memory of what joy feels like to guide you to sunrise. It's a sudden light in the darkness when all others have failed and the giant spider is closing the distance impossibly fast. It is one of the most haunting things I have ever heard and Carl Sagan would be a genius for including it even if he had never done another thing to be remembered for. It sums up what it feels like to exist and persist in spite of the grief and pain inherent in existing better than any other piece of art I can think of.

꘏

In 2025 (this year somehow, impossibly), Voyager 1 will run out of juice and no longer be able to power a single instrument. By 2036, both probes will be out of range of NASA's Deep Space Network and that may be the last we ever hear from them.

In 1949, Willie Johnson's house burned to the ground. When the blaze was dead ashes and the firemen had gone, his wife put dry newspapers down on their sodden, half-scorched mattress and that's where they slept that night. They had nowhere else to go. The damp got into Johnson's lungs and turned into pneumonia. The double whammy of being Black and blind meant that no hospital would admit him. He died in the ruins, effectively homeless. The exact location of his grave is still unknown.

"Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground" is the second to last track on the Golden Record, kept from being the final word on humanity by some upstart schlub named Beethoven. I love that it's one of the only things that will survive us. There is a rightness to it. You hear that song and you think: yep. That's it. That's the one that should be queued up to play us back to our cars while the dirt hits the coffin lid. It makes me so happy that it's out there—will always be out there—and that I get to know that fact.

And now you do too.

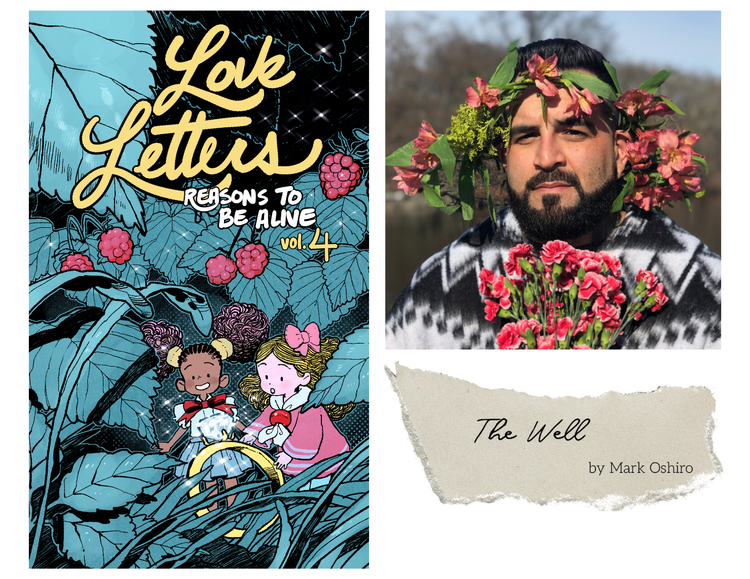

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion