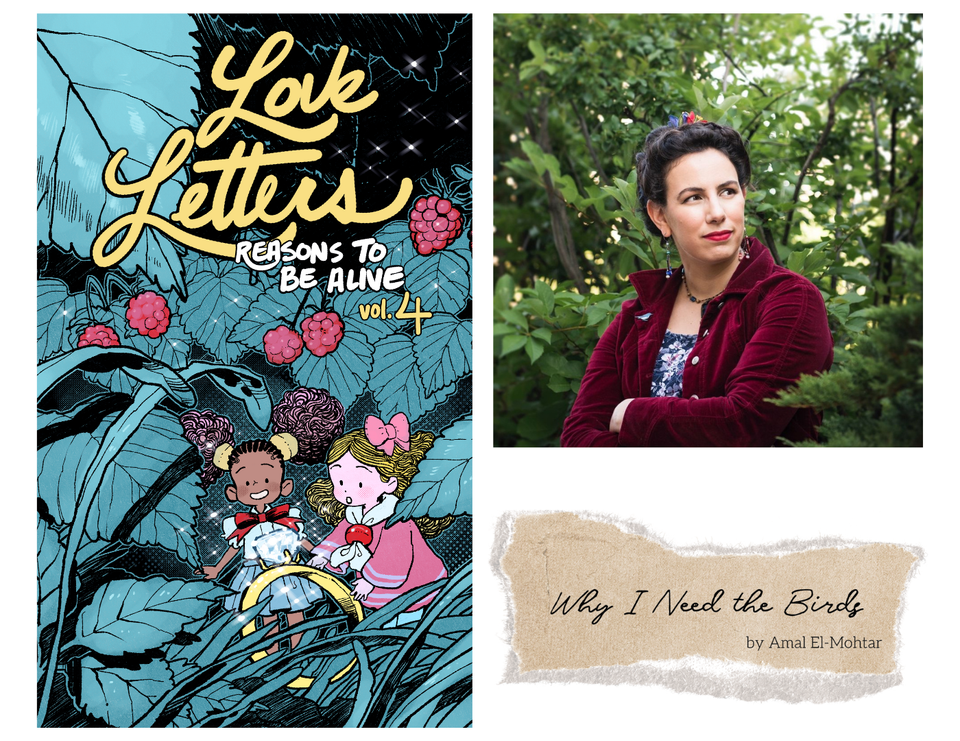

Why I Need the Birds

Amal El-Mohtar is an award-winning writer of poetry and short fiction, and co-author of the New York Times bestselling This Is How You Lose the Time War.

the birds, leading

their own discreet lives

of hunger and watchfulness,

are with me all the way

– Lisel Mueller, “Why I Need the Birds”

In order for me to write poetry that isn’t political

I must listen to the birds

and in order to hear the birds

the warplanes must be silent.

– Marwan Makhoul

The first time I spoke to you about birds was ten years ago, at a convention in Saratoga Springs. Wild geese flew overhead and I pointed them out–it was deep autumn–because I wanted you to hear the sound of their wings. Where I lived, then, in rural Quebec, geese clamoured on the river for months at a time, and I’d learned with some awe that if they flew low enough, you could hear the creaky mechanical sound of their wingbeats, a secret kept hidden within all the other noises they make.

I wanted you to hear it because I loved you, and I wanted to give you something I loved.

I would like to remember, in this moment, whether or not you caught the sound; I would like to ask you what you recall, the way one does, with a friend.

*

Here’s what happens to me when I look at a bird. The world falls away in a flutter of feathers. A deep, untouchable loveliness unfolds between the bird and my awareness of it. No depth of conversation, no misery of thought can withstand the urgency with which I must come to know the bird.

To come to know a bird is to make some wholeness emerge from scattered parts. If I’ve heard the bird, I want to see it; if I’ve seen it, I want to watch it until I learn something about it–its name, its call, the way it moves. But if it’s new to me? If it’s a so-called lifer? The joy–the sheer, effervescent pleasure–is never less than dazzling.

I have this in common with Mandy and Lara Sirdah, twin sisters who live in Gaza and watch birds. In an April 2023 article by Marta Vidal, Mandy says, “The birds help us deal with the pressure of our daily life. They make us forget everything.” Lara adds, “We wish we were birds so we could move freely… The word happiness is not enough to describe what we feel, especially when we see a rare bird for the first time.”

*

Lara shares her name with my niece, to whom I dedicated the first story I wrote for you. In it, I tried to give the sound to you again:

“Have you ever heard the sound geese make when they fly overhead? I don’t mean the honking, everyone hears that, but—their wings. Have you ever heard the sound of their wings?”

Tabitha smiles a little. “Like thunder, when they take off from a river.”

“What? Oh.” A pause; Amira has never seen a river. “No—it’s nothing like that when they fly above you. It’s. . . a creaking, like a stove door with no squeak in it, as if the geese are machines dressed in flesh and feathers. It’s a beautiful sound—beneath the honking it’s a low drone, but if they’re flying quietly, it’s like. . . clothing, somehow, like if you listened just right, you might find yourself wearing wings.”

*

My writing has two very consistent features: pairs of women loving each other, and birds. Sometimes the women and the birds overlap. When next you asked me for a story I sent you a retelling of the Welsh myth of Blodeuwedd, in which a woman built of flowers is punished by being turned into an owl; in my version, she falls in love with a woman whose name means “wing” in Welsh and “hands” in Arabic, a woman who coaxes from her in flowers all the rage she keeps silent beneath her skin.

It astonishes me, now, to recall how much I trusted you: your intentions, your affection, your perspective. We had so much in common. We loved all the same things. We spoke to each other with a gasping fluency for each other’s sentences, racing each other into our shared understanding of friendship, of how much we loved seeing women love each other. We called each other wives in jest, shared rooms and confidences, sang duets, dressed each other’s hair.

But I couldn’t trust you with my rage. You were liberal enough with yours–towards boycotts, towards athletes, towards any principled stand against the nation you claimed–and when your anger hurt and confused me, I thought I needed to work harder to understand you, to protect you from my own pain out of respect for the lineage of yours.

*

I lost you in the same year our book–the book you acquired and edited, about women who love each other from opposite sides of a war in time–became famous. It became famous from a tweet, of all things, something birds do. To this day, people tag me whenever they see a cardinal and a bluejay at their backyard feeders, because of the birds you requested for the cover.

That spring, while geese were flying home to the river where I grew up, we celebrated with each other, sent reams of joyful texts back and forth, affirmed our happiness in knowing each other, in having worked on something so good and wonderful together.

By that fall, as the geese left, you were a different person.

Now I send money from sales of the book you edited to charities and fundraisers that support the victims of atrocities you justified; atrocities which, now–by your own stated logic–you tacitly endorse through your silence. “I sat here and listened to the deafening silence,” you said, in the days after October 7, declaring that no one sufficiently mourned your dead. “I was listening. There was silence.” Always, somehow, a silence deafened you, while people spoke earnestly to you of things you refused to hear: Of drones deafening children before obliterating them in your name, of whole family lineages extinguished by cluster-bombing tents and hospitals.

But it’s true that I kept silent with you–before any of this, before I tried to meet you in your pain and asked you to see mine. Every year, for the ten years I knew you, I watched you celebrate two things in May: An international song contest, and the anniversary of my people’s dispossession. Every year, in silence, I thought, one day, she’ll understand how this breaks my heart; one day, she’ll love me enough to care.

I reproach myself for that. I should have spoken up earlier, before the world between us broke so irrevocably. I should have forced speech from my skin. I should have asked you to listen to the secret creaking anguish at the heart of me, that I kept hidden beneath the clamour of our shared enthusiasms.

But I was trying to find your wholeness from your parts.

I wanted you to hear me because I loved you.

But you loved the warplanes more.

*

Every time I try to call someone’s attention to a beautiful thing, I am writing a love letter. What is love, after all, but a quality of attention, gazing as a gift. We knew this so intimately, you and I: that to love something was to share it, and to share it was to unfold yourself into a tender vulnerability. To lift your voice in song; to spread wings as you fall.

Our friendship was beautiful, I think. I treasured it deeply. And I still want to share beautiful things whenever I can.

Here is someone I loved. I am giving her to you. You may not recall.

I wish you a silence in which you can hear birds sing.

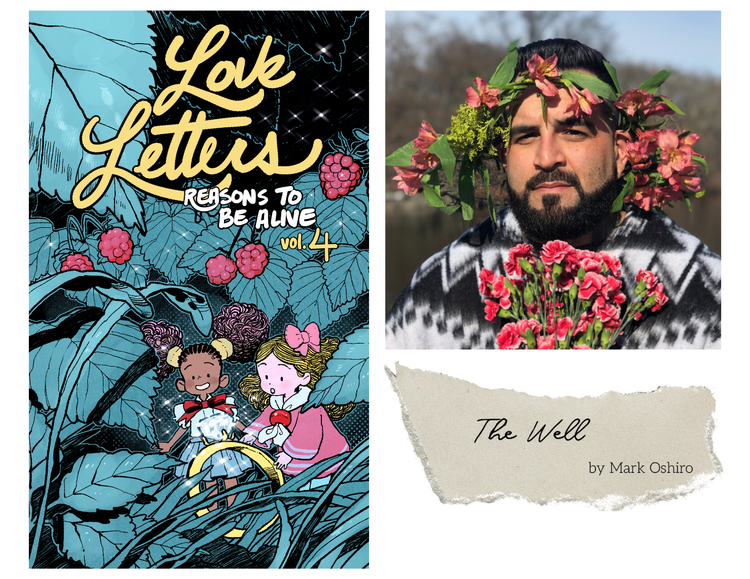

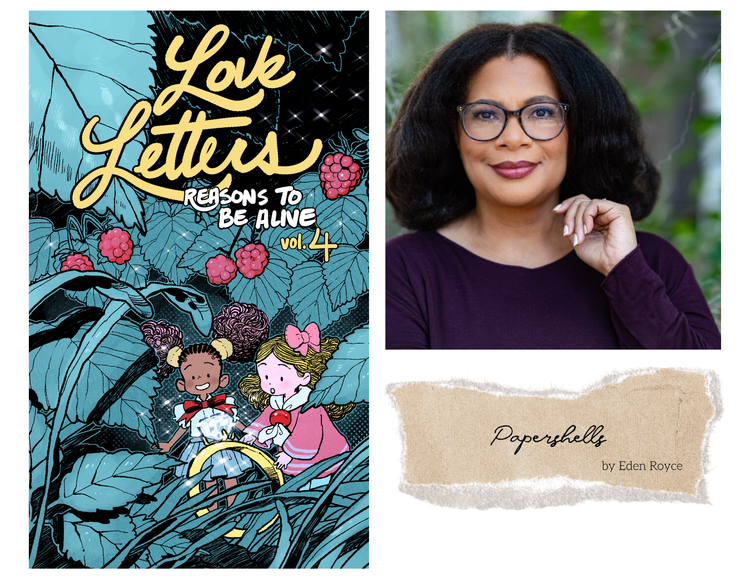

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion