The Party Downstairs

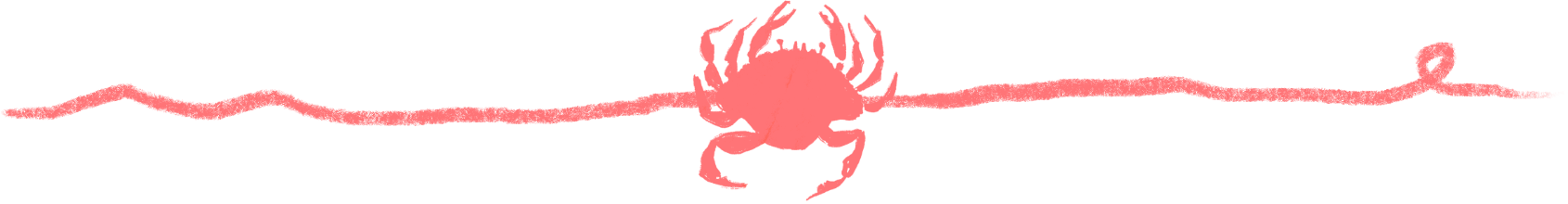

Helena Fitzgerald (she/her) has published creative non-fiction and essays in outlets including The Atlantic, The New Republic, Wired, Bookforum, Food & Wine, Rolling Stone, GQ, Hazlitt, Catapult, Elle, Airmail, Nylon, New York magazine, The New Inquiry, and many others. For many years, she published "Griefbacon," a newsletter of first-person essays themed around romantic love in various forms. She also co-authored "The Dry Down," a newsletter about perfume. She's currently at work on a proposal for an essay collection about romantic love and humiliation, as well as a novel about Northern California in the late '90s that she's sometimes referred to as "a generational saga about the internet."

It’s a truth at least widely, if not universally, acknowledged that the best part of a party is leaving the party.

I love parties, I sincerely do, even as a person who’s afraid of them most of the time. You have to be a certain amount of stupid to enjoy a party, which creates the danger of aging out of them but also keeps that from being inevitable; one form of grace available in the world is the fact that it’s possible to be stupid at any age. I love parties for this reason and many others. What I love even more, though, is going home, getting into sweatpants with my makeup still on, and gossiping with my husband about the party we just attended. When I was younger, my favorite part of a party was when I’d go home and write long emails with my best friend about the party we’d just gone to; it felt necessary to do this before we even went to bed, or, if we were catastrophically drunk, first thing when we woke up the next morning, no matter how bad our hangovers or how pressing our workdays. The part of the party that truly mattered to us was the part that happened after we’d left.

Even as the host, the best part of a party is still leaving the party. It’s when the door closes behind the last guest and I can collapse on the now-empty couch, or when everyone’s gone home except one or two very close friends, when the room's a late-night mess and the party turns from an adult occasion to a teenage sleepover.

There’s yet another version of this exquisite party-departure, a sort of alchemical trick that allows going to a party and leaving a party to happen simultaneously. One tiny and particular joy that makes life, in its stupidity, its obligations, its gossip and its outfits, its running-late texts, its overheated kitchens and its nervous small talk, feel worth it to me is the sound of a party downstairs or in the next room after I’ve left to go to sleep. Through the wall, or up from the stairs, the gathering and conversation and laughter continues on without me, making a noise like the ocean, or the rain, or how the other cars speeding past sounded when I would fall asleep in the back of the car on a road trip as a kid.

I grew up in a big house in which my parents often threw parties. The house didn’t belong to us; rather, it was a perk included with my dad’s job as the head of a small high school. The house and the job came with the implicit agreement that he would throw several parties a year for the faculty and staff of the school. Growing up in these circumstances meant I often fell asleep listening to someone else’s party downstairs as it unraveled into the late hours and the last guests with their shoes off, sitting on the floor. I spent a lot of evenings in that house as a kid hovering just outside conversations about things I’d never heard of and people I didn’t know, a constant and familiar background noise as sentences blurred into an indistinct musical glow and then faded away entirely.

Listening to the party in the next room as I fell asleep was an experience common to my childhood, which means nostalgia is almost certainly part of why I’ve continued to find the sound of a party in the next room so comforting decades later. However, nostalgia isn’t the main reason I feel so profoundly at home in this small and particular experience, falling asleep while laughter rises from downstairs and wafts up through the floor. My attachment to a specific type of party-leaving has, I think, more to do with the determinedly illogical ways I’ve grabbed at it in adulthood than with the way it fit into my childhood and adolescence.

I’ve lived in New York City my entire adult life, which means I’ve only ever lived in very small apartments. Nowhere I’ve called home since leaving for college has ever had stairs inside it; it’s only in my thirties that my apartment has even had another room with a door I could close besides the bathroom. In my twenties, only one couple in my whole loosely-connected friend group had the kind of apartment where they could reasonably host a party. This meant that all of us ended up there constantly, clustering and sprawling across their living room, sitting on the counters in their long, skinny galley kitchen, and climbing out their window to their roof. I didn’t always know everyone who came to these parties, but I was very close friends with the couple in whose apartment they took place, and I felt perhaps more entitled to make myself at home in their home than I should have. I was trying so hard in those years and getting it wrong so much of the time. I was always running so fast, figuratively and sometimes literally. I was always so broke, and always so scared, and often so lonely, and I was so tired, the kind of tired you can only be when there’s no space to admit to yourself that you’re tired. So, when the room lapsed into other people’s inside jokes, when the party became something in which there was no clear way to include myself, I would fall asleep in a big chair or on the sofa, letting nearby voices fade to a soothing background murmur. I hadn’t gone upstairs; there was no upstairs to go to. I hadn’t even gone to the next room. It was that same old thing, though—the first version of it that I experienced in adulthood. Falling asleep just outside the soft border of the party while it kept going on around me. It was the best sleep I ever got in those years.

My life is a little less precarious now. I live in a nice apartment, but it’s still just three rooms, and not any kind of place where it’s possible to go upstairs. I call my apartment my house, and I call all my friends’ apartments—almost none of which are the size of a house, almost none of which have stairs—their houses, too. Everyone in New York calls their apartment their house, as though if you loved something enough you could change its shape by the force of what you feel for it. And in these small spaces that we call our houses, that aren’t really houses at all, some version of falling asleep to the sound of the party in the next room takes shape again, even as it makes little sense in the material circumstances. Maybe whatever insists itself into existence means more than whatever simply arrives.

My apartment is too small for parties, but I’ve hosted them there again and again anyway. Even the tiniest group, just eight or ten people, becomes, in five hundred square feet, a raucous crowd. This piling-on, overcrowded, everyone-talking-at-once warmth can make any small gathering blossom into the whole saturated idea of a party. It’s when I’m most able to remember that there’s some reason to shove our bodies into the same spaces with one another, that the rewards of putting up with the annoyances, impatience, and awkwardness of other people are far more than the costs of it. There aren’t any stairs to climb, or even much of a hallway to retreat down, but I can still say goodnight and close the door to the bedroom, and drift off to sleep listening to people I love tell jokes and talk over one another. My house isn’t a house; it’s three rooms in a building that somebody else owns. But at these times, half-asleep with my friends’ voices audible through the wall as the party goes on without me, that these three rooms feel more like a house than any house in which I’ve ever climbed the stairs to go to bed.

Falling asleep listening to the sound of a party you aren’t part of might sound lonely, but it isn’t; it’s perhaps the furthest thing from loneliness I can think of, unlike a party itself, a thing that can quite often be shockingly lonely. The sound of the party going on in the other room means feeling so much part of something that I don’t have to strive to make myself part of it. It’s allowing what I love to exist without me, and loving the version of it that doesn’t include me just as much as I love the one that does.

There’s an awful, clawing sense of scarcity that infects my life and the lives of everyone I know, a scarcity that’s unavoidable in the poisonous end-of-days world in which we live now. A party can’t solve that, and neither can leaving the party while it carries on in the next room. But this feeling, this overheard background noise, other people’s laughter and friendly arguments, can offer something to counter that sense of scarcity, however immaterial the counter-argument may be. It’s a glimpse of a world where there is always enough, where there’s no worry about missing out because nothing is finite; if I miss out on something, there’ll be another chance. Whatever I don’t say tonight, I’ll be able to say tomorrow, or on another day, sometime in the long future, at another party, because there will always be another party. That the party continues is the point; I’m neither its subject nor its engine. Love is not predicated on the space it makes for me at its center, and what I love still exists without me making sure of it. Love itself is enough, and anywhere we gather in a warm room to keep out the cold can be a house if we decide it is. The sound of the party as I fall asleep is the sound of love getting free of the notion of ownership. It’s what can be held without grasping, and what can be made larger by use and not smaller. It’s loving something without needing to remind what I love of my own existence, without having to hold it tightly or at all. It’s loving something and listening to it continue on as I fall asleep, and still being sure that what I love will be there in the morning.

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion