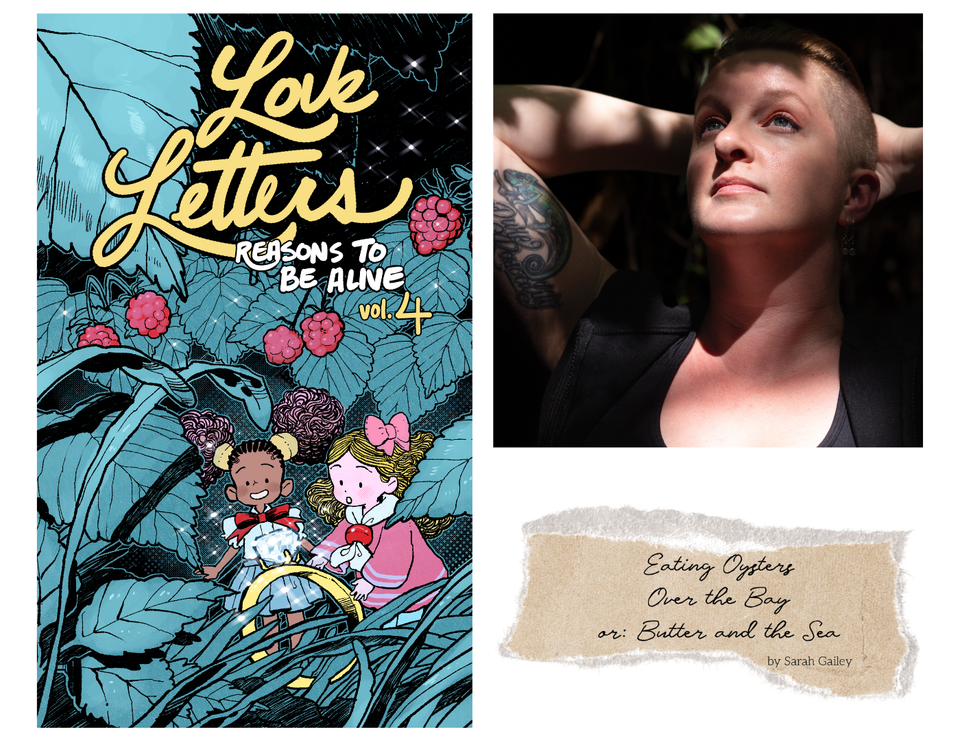

Eating Oysters Over the Bay or: Butter and the Sea

We forgot to bring jackets. We should know better–this is the peninsula above the bay, where the wind and fog come in cold. We’re lucky that the day is warm.

The menu is printed in sky-blue letters on thick, creamy white paper. The tables are worn wood, warm to the touch. They sit under dark shade umbrellas on top of the dock, bumping right up against the railing that is the only thing to keep us from falling into the sea like diving cormorants. The sky is clear save for one scudding cloud, and there are oysters in the bay, and they are going to be ours.

We look over the menu only briefly before deciding to order obscenely, decadently. We drove for hours up the winding coast to be here. We will not hold ourselves back from anything we desire. The waitress gives us an approving nod as our order expands. Four of these, four of those, one order of each thing in this section of the menu. We laugh as she walks away, certain that we’ve reached far beyond our grasp. We have no idea what we’re capable of.

The wine arrives quickly. As we take our first sips, a pelican lands on a nearby pylon that sticks up out of the water. The pylon is one of six, all half-rotted, the remnants of a dock that’s been dead so long that even the suggestion of it is forgotten. The water climbs each one, eating away at the dark wood year after year, and seabirds use the tops to rest and roost. We watch them land and take off, dive and surface–dark oil-slick cormorants, always bigger than we think they’ll be, and prehistoric-looking grey pelicans that float weightlessly across the air before hurtling into the gentle waves with impossible gravity.

The first set of oysters is upon us. A set of metal rings raises the bowl of rock salt to the level of our throats. These oysters are hot–grilled just long enough to saturate their flesh with woodsmoke. Some of them are glazed with thick brown barbecue sauce; some are densely crusted with cajun seasoning. We save these for last, knowing that their flavor will be strong enough to leave our palates numb. The other half of the dish has the deepest oysters on it, their shells turned to chalices, their flesh swimming in spoonfuls of still-simmering butter. The butter is infused with miso and kombu and garlic and lemon.

I choose a garlic-lemon oyster; you choose a miso-kombu. The shell is almost too hot for me to hold. I tap it against yours before lifting it to my lips and tipping my head back. The scalding butter drops into my throat, searing the very back of my tongue, and the oysterflesh follows–smoke-perfumed and saline, richly slick with hot butter, wealthy with the golden flavors of garlic and lemon. I chew just once–an oyster doesn’t want to be chewed much, but this one is cooked just beyond the raw tenderness that would allow me to swallow it whole.

When I open my eyes, I can see that you’ve just experienced the same revelation I did. Your eyes are closed, your lips slightly parted to exhale the steam of the butter. The waves below us lap at the dock we sit on. There is a breeze off the water, damp salt in the air. When you open your eyes, I glance away, pretending to give you privacy. When I look back, you’re watching me.

The raw oysters arrive a minute or so after we finish the grilled ones. The first round was delicious, but this is the main event. The waiter tells us where each pair is from; we immediately forget. The metal bowl of ice is coated with a thick layer of cold condensation. A dish of mignonette nests down into the center of the ice, a school of diced shallots swimming in sweet vinegar. Lemon wedges bejewel the spaces between the oysters, which glisten with wanton invitation.

We regard them with undisguised lust. We fall upon them as a single open mouth.

All is appetite. We take them in their pairs, tasting and comparing notes with the efficiency of the ocean dismantling a ship. The first pair is light and sweet and tastes like a first kiss. The second is bright and fresh as the sun on the surface of the water. The third tastes like meat, like parted flesh, like an animal that would bite back if it had the chance. The fourth is a brilliant salt slap. The mignonette is sharp, the lemon is an iridescent blossom, the bottle of housemade hot sauce remains untouched. The shells are rough and flaky against our lips. The oysterflesh is a slip of damp silk across the tongue.

The thing is that the air here tastes like the sea, and the warmth of the wood under our hands feels like the sea, and the water lapping against itself makes music out of the sea. We are on the deck, playing at being on land, but every bite we take brings the sea into us. With every bite we are shocked at our own audacity, delighted at our own capacity to consume. We revel in the subtleties and unsubtleties of the flavors we encounter. We are no different from the pelicans and the cormorants and the terns. We are eating the world, and we are alive.

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion