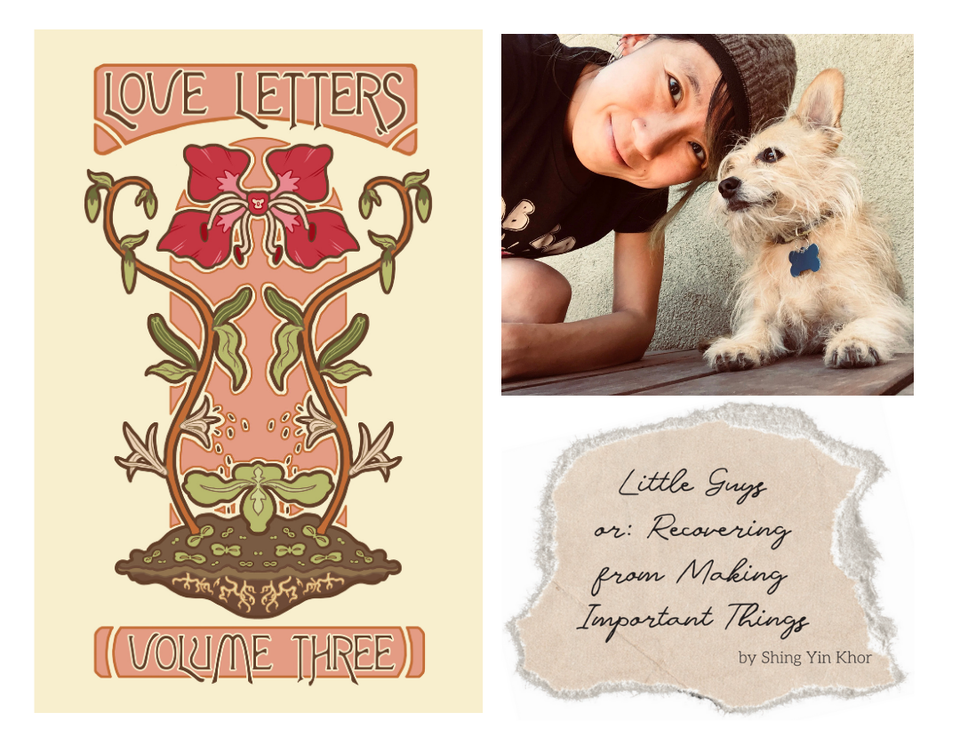

Little Guys

or: recovering from making important things

Shing Yin Khor is an Eisner and Ignatz Award-winning graphic novelist, Indiecade Award winning game designer and wooden marionette builder based in Los Angeles, CA, by way of Malacca, Malaysia. They are interested in the myths of nostalgic Americana, new human rituals, keepsake games, and the stories of created spaces. Their second graphic novel, The Legend of Auntie Po, was published by Penguin Random House in June 2021, and was a National Book Award finalist. Shing is currently fundraising for another Little Guy project called The Last Fifteen Minutes; you can learn more and support the Kickstarter here.

In 2021, I released a critically acclaimed (but not commercially successful) graphic novel about American myth and the Chinese Exclusion Act and queerness, the kind of thing that gets your name misspelled in the New York Times and mispronounced on some pretty big award stages, which is the sort of success that’s still hard to talk about because it was more than I ever expected, or knew how to want, but ultimately not anything that was very much at all. Mostly, it made me a mid-career author who wrote about serious topics, when I only knew how to work as an underdog, upending some ingrained belief systems about myself and my work that I didn’t even know existed.

My next book under contract was, and still remains, two years late. I mention this as the major reason for my deep burnout as a cartoonist, that paralyzing and overflowing buffet table of “what if I never make anything good again” with healthy side dishes of “I have exactly one story and that’s it” and a dessert selection of “honestly that wasn’t even that good a book and everyone is wrong about me.” After building a career on making work with meaning, I was exhausted by meaningful work.

I’ve been making things my entire life. My mother was a ceramicist. I grew up knowing not to pour clay water down the sink, and how to score and slip, and how to make little pinch pots with no formal training. I grew up making lumps with no particular aesthetic value or skill, and at some point, I stopped doing that because I wanted to be a real artist, and being an artist meant making important work about race and queerness and politics. It meant having opinions and defending them, and being witty and relevant, and it felt like there wasn’t much room for things that didn’t have any stakes.

There is a lot to write about the process of slowly healing this intense burnout, but here is one part of it. I impulsively accepted an invite from a professional acquaintance(now a friend) to go to Crete for a week, which led me to standing at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, where I saw a display case filled with terracotta beetles, formed by human hands three thousand years ago. I went to find someone who had been a stranger to me just two days ago, a biologist who had spent some of our shared time together intensely observing insects, and said “Hey. I FOUND A BUG.” We scampered over to the row of clay beetles. I pointed and said “BUG!” and she said “BUG!” and no more understanding of this work was needed because several millennia ago, a human person formed clay into a ball, squeezed some part of it to form three horns, and produced something that remains recognizable, thirty centuries later, as a rhinoceros beetle, and a little guy.

On the flight home, I wrote a short manifesto about making little guys (which is reposted at the end of this essay, but the sentiment will become very obvious in the coming paragraphs). A day after adjusting to my timezone, I went to the ceramics studio, a place I had been dallying with in the way one might dismissively toy with a Tinder fuckboy (except my friends want my mugs more than they want fuckboys), and I made a lumpy little guy. I started with a circular lump and I coaxed four legs out of it. I gave it a tail. When he came out of the kiln two weeks later, I understood its purpose, which was nothing at all and everything in the world. It was simply an object in the lineage of sculptors before me who dared to put their hands in mud and made a little guy. It was a small invocation from me that said “I am still an artist. I can still make something.”

I used to be afraid of making little guys. Making little guys wasn’t really serious work and I wanted to be taken seriously. Making little guys was a silly thing to spend time on, something undignified, only one step further than pre-school Play Doh experiments. But little guys don’t care what I think about them. They have simply been present, an Inuit snouted animal carved from ivory from the 10th century, a Hellenic terracotta sheep from 1400 BC, a 7th century metal dragon from China.

This making of little guys is something that has been central to the human experience, part of the indefatigable human capacity for joy and tenderness for small things. And in a time of fascism (fuck fascism) seeping into every crevice of our daily lives, at a time where the horrors pile up, and the looming threats feel too big, I think of the small things. In 1942, a young teenager named Josef Bäuml does a drawing exercise to relax the hand, in a clandestine art class led by artist Friedl Dicker-Brandeis in the Terezin concentration camp. He draws spiral upon spiral, practicing the rhythm of an easy spiral on paper. and in the corner of this page filled with spirals, he turns two of these spirals into two little snails, with silly little antenna and eyestalks, with enough attention to the shape of the lower tentacle and mouth to suggest that he was a person who has looked closely at the shape of a gastropod in profile before. Both Josef and his teacher are sent to the extermination camp Auschwitz in 1944; both are murdered there.

Rome burned, Nero fiddled, and collections of little guys dating back to the Great Fire of Rome persist, now twice fired by flames. Like most contemporary ceramicists, I fire my clay figures at least twice. The first bisque firing makes the clay stable, the second, at higher heat, vitrifies the clay body and makes it strong. It is only human to feel tenderness for small things, to carve, to mold, to make with the sweet instinctive compulsion to preserve the small things we hold dear, like our memories of what a snail looks like, our dead cats, the times we held something soft and innocent in our too-big hands.

When too many things matter, in my work, in the world, when too many things require intense thoughtfulness and anxious deliberation, I revert to my primal form as an artist and make a little guy. The exact shape of the little guy does not matter, except that perhaps it is the only thing that matters. The knowledge of how to do this is encoded in my human lineage, like my mother before me, like her mother before her, like generations of humans who were compelled to make something out of not very much at all. The little guy is simply the human instinct to make something with little guy energy. If you carve a carrot into a bunny, that is a little guy. If you fold paper cranes from chopstick wrappers, that is a little guy. If you put googly eyes on a lemon, that is a little guy.

This is an indulgence. I think of the often quoted Mary Oliver poem–you do not have to be good, and I know very well that it is a poem about wants and indulgences, but I like to take it literally. You do not have to be good at this. You do not have to make a masterpiece, you only have to take up your tools, faltering and flawed and sometimes not tools at all, and make a little guy, in a lineage that stretches several millennia of humans who have taken up their tools and made a little guy. And so, I will.

MAKE LITTLE GUYS: A manifesto inspired by that one Tumblr post, and Minoan clay figures. Watch a video or listen to narration here.

Make little guys.

Make little guys in the lineage of our ancestors, who stuck their hands into a pile of mud and made a little guy.

Little guys transcend and inhabit all ages and all cultures and all continents.

Little guys have been here forever, and they will outlive us.

Make little guys because this is a primal human instinct, a deep longing made physical and often kind of round.

This is the impulse of many millennia, that runs through our beings.

This is not to serve as a definition of what a little guy is. There is no need to define a little guy, we all know what a little guy is.

If you have a little guy that has a purpose, let it fulfill it.

If you have a little guy puppet, let it dance.

If you have a little guy pitcher, let it pour.

If you have a little guy whistle, let it sing.

If you have a little guy figure, let it be played with and broken and glued together again, because something precious is something loved, not something perfect.

Make little guys in the shape of those you have loved, make little guys in the shape of those you have lost.

Make little guys because this is the only way you know how to hold them again and because these little guys yearn to be held.

Make little guys out of clay, out of wood, out of felt, out of iron, out of paper, out of pixels and code, but little guys have to be the work of your hands and the work of your heart.

A little guy made without heart is uninhabited and will not have the correct little guy energy.

You'll know.

In Heraklion Archaeological Museum on Crete, there are collections of little hand-pinched four-legged creatures, made with no particular skill or technique, as if a child was playing and made a little guy, and another child said, "I want to make that little guy too."

If you have made a little guy, and someone says "how did you make that little guy," you must show them.

Little guy making techniques should not be hoarded, they belong to a collective human impulse greater than any one of us humans.

When we die, let us be buried with little guys, so that generations past us, if we are lucky to have generations past us, will find them and say, "What a little guy. They must have been loved."

And they will see our little guys in their little guys and their little guys in our little guys, and they will make little guys in our lineage and in the image of our little guys and in the image of what we have made, and we will live forever.

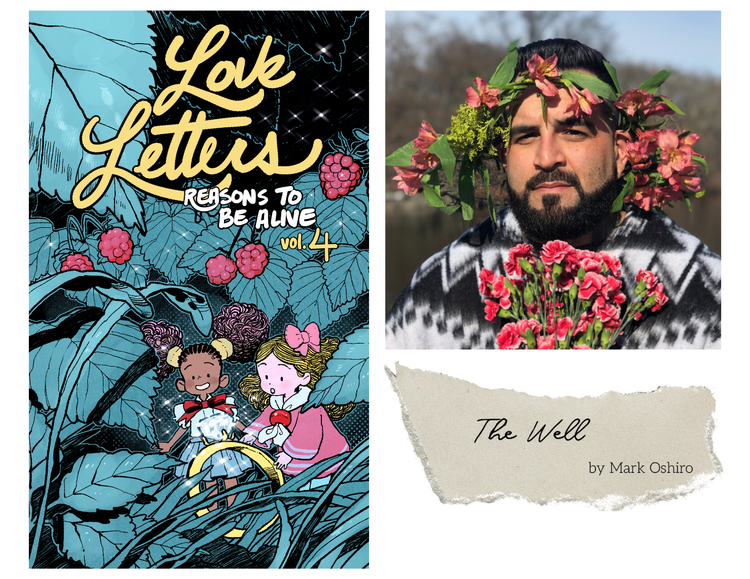

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion