A Love Letter To: The Changeable Sea

Premee Mohamed (she/her) is a Nebula, World Fantasy, and Aurora award-winning Indo-Caribbean scientist and speculative fiction author based in Edmonton, Alberta. She has also been a finalist for the Hugo, Ignyte, Locus, British Fantasy, and Crawford awards. Currently, she is the Edmonton Public Library writer-in-residence and an Assistant Editor at the short fiction audio venue Escape Pod. She is the author of the Beneath the Rising series of novels as well as several novellas. Her short fiction has appeared in many venues and she can be found on her website at www.premeemohamed.com.

I was lost, but I had set aside a day to get lost; I told myself that I was on a quest, and all roads in a quest lead you, inexorably but imperceptibly, to the place that the narrative needs you to go. The quest at that moment led me to a small rocky outcrop, which I climbed, and sat down awkwardly, facing the sea.

I had been eyeing it for a while—the rock I mean, not the sea, which I could not help but have in my field of vision most of the time—judging its climbability, its likelihood of pitching me off or shattering, fracturing, throwing me off it like a spooked horse. I am not an athletic person. I got up the relatively shallow slope, found some natural breaks in it that offered themselves as steps, and settled in. The air was cool, the sun hot. Under my jeans the dark gray stone radiated a pleasant warmth upwards, welcoming me.

You have to let strangeness wash over you sometimes, you have to let it move on its own, not try to harness or capture it. So the strangeness came and I held my breath: I was four thousand miles from home, I was alone, and no one was telling me what to do or where to go. Furthermore, confusingly, no one was telling me to shut up. No one was telling me to make myself invisible; no one was telling me I wasn't wanted where I was; no one wanted me to move from my spot to make space for my betters. (Except the seagulls, but there is no accounting for the opinion of seagulls.)

I sat in the sunshine, deeply confused, smelling the salt and the iodine, looking down at my boots, which already boasted some questionable dark-green grot from walking near the shore. The dark stone itself resembled a fine-grained basalt: not the stone of home. None of those things should have been possible. What had happened?

On the one hand, or on one plane of reality (the sensible, solid one, with seagulls and rocks) I had gone to Dublin to attend WorldCon, and had picked a few days to go outside the city and do things I hadn't had time for on my first trip to Ireland seven years before. Howth could be reached by train; it seemed nice enough; I could not think of a reason not to spend a day there.

On the other hand, on the plane of reality I was used to, I was a little dazed, or dazzled, by what I was doing, and constantly looking over my shoulder for the psychic ghosts of persecution past. I had been raised quite differently from all my friends—even, somehow, from my brother, who should have been cringing under the same helicopter shadow as me. It was not to be. My every move was monitored, my every friendship scrutinized; I could go nowhere on my own, and was questioned intensively if I was with friends (most of whom, over the years, understandably faded away).

I slowly stopped asking for permission to do things, go places. I went only where I was told. I did only what I was told. By the time I was twenty, my parents had hammered me so persistently around the mould they created for me that I could barely perceive a future where I was free from their control.

So I tried to kill myself.

It didn't work, of course. Due to a weird confluence of circumstances (health, location, method) it almost worked. I look back at those days and I see someone so absolutely crushed by mental illness and terror, so very much a shade of herself, that I'm impressed she managed to lift a hand to do herself harm.

My parents found me in the hospital, where I had been brought by campus security. I was bandaged up, instructed to lie—a car accident, something, it was of no import to them—and packed off to finish my degree. I missed about three days of classes. Six weeks later, I was blinking in the sunlight outside the Butterdome, capped and gowned and expected to know what to do with the rest of my life.

I didn't want it. I didn't want there to be a rest of my life, to be exact. The next few years were a blur that feel even now in my memory like what I imagine a bird of prey must feel with a broken wing: the pain, the flapping, the anger, the dim realization that I'm not getting much lift, the flapping, the flapping, the flapping, the hunger, the resignation.

I couldn't think of anything to live for. My parents, angry that I hadn't gotten into a masters program (unaware that I hadn't applied), seemed relieved when I told them I was going back to school for something else.

And suddenly—miraculously—I got lift. That second degree came with an internship far from home, a prestigious one, with a research branch of the federal government. I was still asking myself, "How could they possibly say no to that?" instead of asking myself why it might be their yes or no that mattered. I moved out there in the dead of winter, to a prairie cold so deep and familiar that for a few panicked weeks I woke up at night thinking I hadn't escaped at all—that I was still home, with my wing still splinted, still being fed by faceless giants.

But no. I could do what I wanted, when I wanted, answerable to no one, seeking no permission, far from watchful eyes. It didn't feel like a second chance at life; it felt like life for the first time, capital-L, Life.

And Life was strange and terrifying and full of surprises. It tasted like drinking wine with my labmates after a performance of Die Fledermaus, it looked like the sun-dappled flower gardens of the houses in the rich area of town where I went for walks. It had the friendly, vegetal smell of the horse my friend taught me how to ride (Captain. His name was Captain. He bit me, but I don't hold that against him).

This is a love letter to freedom and choice, but it is also a love letter to surprises—to never knowing what is around the corner. It sounds trite, it sounds glib, it sounds like it should be engraved on a wooden plaque in a millennial-gray kitchen, but it's still true. There is a direct line between that night in the hospital and that day on a dark gray rock at Howth.

We don't know what happens next. We can't. We think we do, based on available data, but we really don't. And I am living for that. I'll live for that.

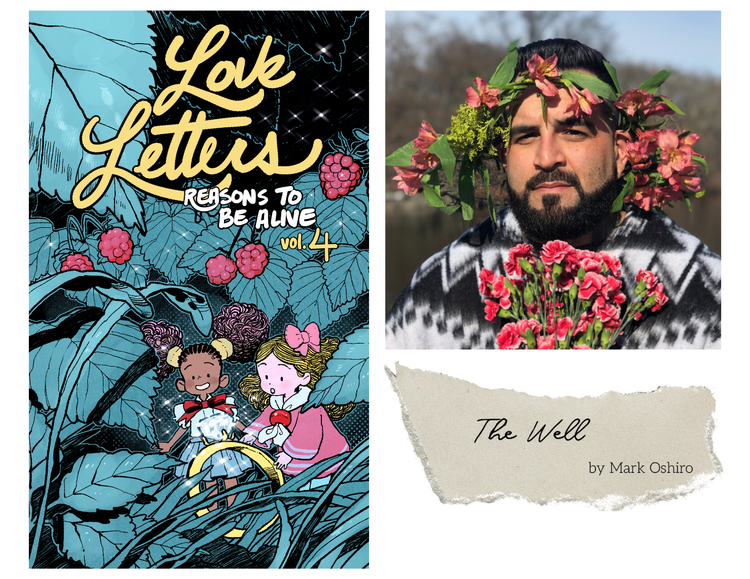

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion