Mourning Espresso

Annalee Newitz writes science fiction and nonfiction. They are the author of three novels: The Terraformers, The Future of Another Timeline, and Autonomous, which won the Lambda Literary Award. As a science journalist, they are the author of Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind, Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age and Scatter, Adapt and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction, which was a finalist for the LA Times Book Prize in science. They are a writer for the New York Times and elsewhere, and have a monthly column in New Scientist. They have published in The Washington Post, Slate, Scientific American, Ars Technica, The New Yorker, and Technology Review, among others. They are the co-host of the Hugo Award-winning podcast Our Opinions Are Correct, and have contributed to the public radio shows Science Friday, On the Media, KQED Forum, and Here and Now. Previously, they were the founder of io9, and served as the editor-in-chief of Gizmodo.

CW: discussion of suicide

I have a small espresso machine, lacquered bright red with silver chrome accents, whose functioning is as quirky as it is dependable. It is the third espresso machine I’ve owned as an adult, and unlike its predecessors, it never leaks or explodes. My previous machine used to blow out randomly. It was a steampunk sensation with a golden eagle hood ornament on top, operated by manual lever. Sometimes it built up so much pressure that the portafilter would unscrew itself from the group head and smash into my cup mid-pull, filling the kitchen with glass shards and grainy brown drops of espresso.

I lost a lot of good cups that way.

Despite this dangerous, chaotic history, making espresso drinks in the morning is now a comforting ritual. I have one of those dependable machines now. My collection of unshattered cortado and cappuccino glasses is a jumble of many colors—pink, blue, green, amber—that catch the morning light from the kitchen windows. I always make coffee drinks for whoever is at my house in the morning, which means I’ll start by placing two or three cups to warm on top of the machine while I grind the beans, check the water levels, and push the button to start the tiny boiler going. As the machine builds up pressure, I pour milk into a steamer carafe and put on a morning news podcast.

I choose the colors of the glasses to tell myself a tiny story as I tamp down the grounds in the portafilter. Sky blue and amber for hope in autumn; pink for the woman I love; green to keep me focused on life when I’m tempted by oblivion.

Over the years I’ve learned to pull a mean espresso shot with a thick, tan layer of crema on top. The smell is a promise: today will start richly, with a flavor that’s nutty and warm, pleasing and stinging the tongue in equal measure. I top it with microfoam, whose infinitesimally tiny bubbles give it a velvety texture. It’s soft, almost like whipped cream, and when it slides into the coffee the whole drink feels lighter.

That is my promise to the people I love, to whom I bring the full cups: You’ll sip darkness through a cloud.

As I froth the milk, the steam wand makes a high-pitched whine that reminds me of my childhood, when my father taught me about how to steam milk for espresso drinks. But, like my old espresso maker, he was prone to catastrophic explosions.

Abusive, morose, obsessive – he was a lonely guy who made himself lonelier by driving nearly everyone in his life away. He brought a wrathful precision to everything he did. But when he cooked—whether a simple stock or an elaborate four-course feast—it metabolized into joyful excess. He would smile and joke around and bring in a platter loaded with so much food that nobody could possibly eat all of it. And then, when you couldn’t believe how stuffed you were, he would bring out the desserts and cappuccinos.

Unfortunately one cannot cook and make espresso all the time. And when his wrath turned elsewhere, it burned through three families and countless friends, exiling all of us from his life for imaginary crimes he could conjure up as easily as spicy eggplant stir fry. Finally, after one of his long stretches of angry silence, I got the call I had dreaded for years. His neighbor had alerted the police because my father’s cat was roaming in the backyard, looking starved. It was a red flag, because he always made sure that cat ate fresh shrimp every day.

They found his body on the floor of the empty guest bedroom. It had been there for weeks. Alone, with no one left to feed, my father had at last turned his rage inward and killed himself. All he left behind was a note for me and my step-sister with careful instructions about how to find the chicken broth he’d left in the freezer. The coroner said that one of the last things he’d done was make an espresso for himself; he left the cup in the sink.

As I turn on the coffee machine, sometimes I can’t help but think about my father’s last moments. Now you can understand why I spend an extra minute or two admiring the way the light glints on the green and blue cortado glasses. Why I tell a story about how their cheerful colors can ward off death. My father implanted his rage and sadness in me long ago, but he also showed me how to exorcise them.

Nourishment.

That’s why I choose to recall him instead as he was in the kitchen, taking our coffee requests and frothing up milk. He loved to figure out what everybody’s favorite drinks were—latte, cappuccino, café au lait?—and give us exactly what we wanted, in heated cups of the perfect size. Did we want a thick slice of toast and preserves with that? What about a grilled cheese, pepper jack and cheddar oozing into the pan to form a crispy lace skirt?

This is how I choose to live, to survive the dark thoughts. With each creamy waterfall of espresso from the two spouts in the portafilter, I recall where I came from, and remind myself that there is always another path. I serve up the morning coffees as he once did, and I stay here on Earth as myself.

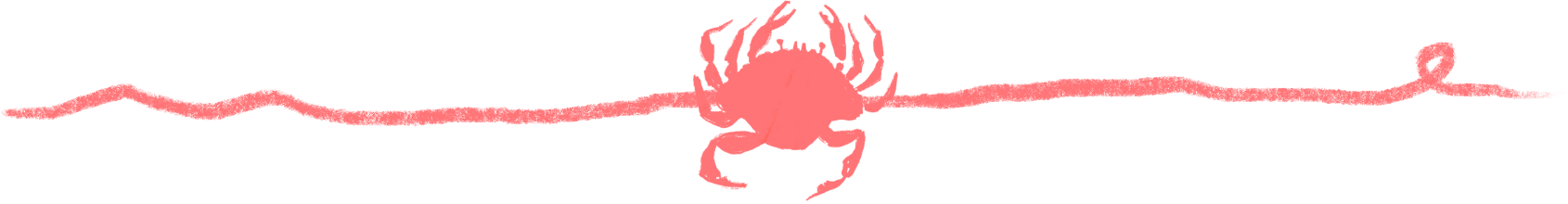

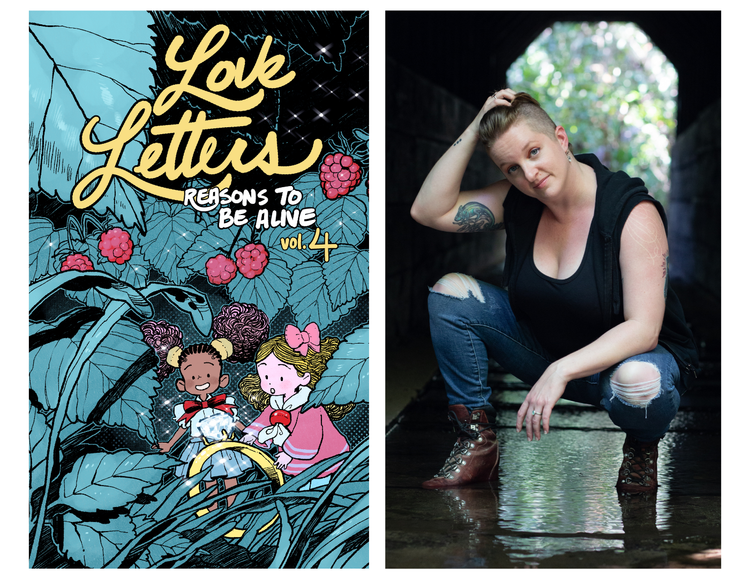

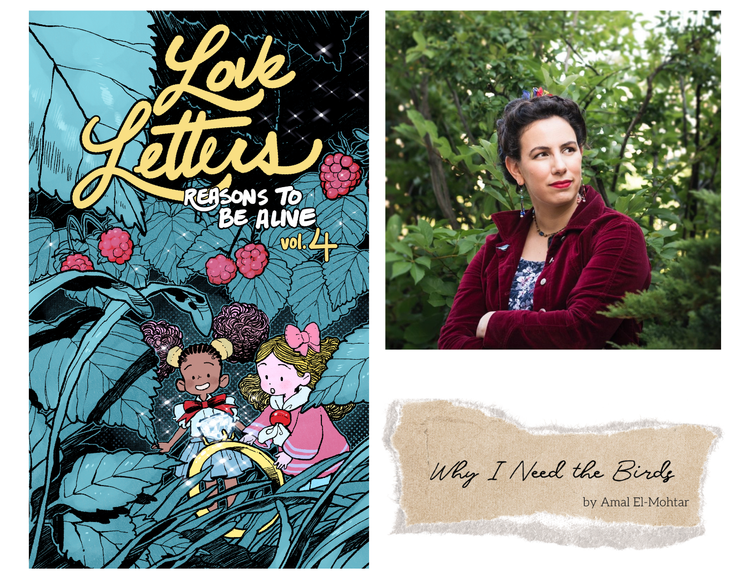

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion