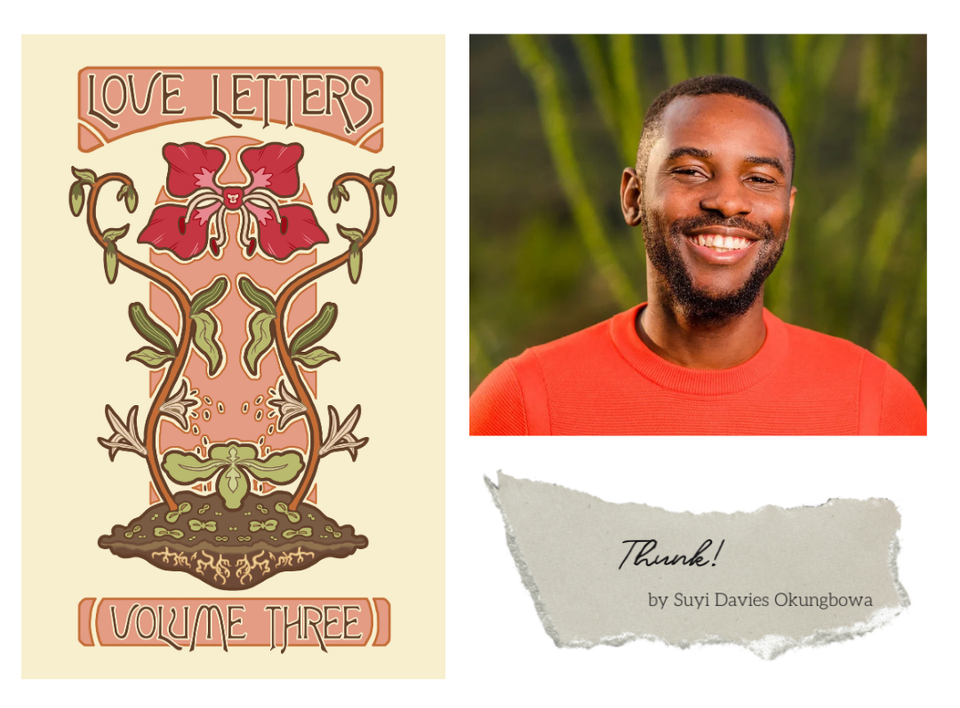

Thunk!

Suyi Davies Okungbowa is an award-winning author of fantasy and science fiction. His latest books include Lost Ark Dreaming (2024 Nebula Award finalist), Warrior of the Wind and Son of the Storm (the Nameless Republic epic fantasy trilogy) and The Intergalactic Empire of Wakanda (a Black Panther novel). He lives in Ontario, where he is a professor of creative writing at the University of Ottawa. Find him online at @suyidavies and SuyiAfterFive.com.

It’s the early 90s in a small, ancient city in mid-western Nigeria: A decade of economic and political upheaval, military coups and counter-coups, sly promises of progress and prosperity that never quite arrive. A time of major swings in disposition, of always being on the cusp of something. If you grew up in such a city at such a time, you grew like a weed—scraggly, in the cracks, finding light and nutrition wherever you could. Sometimes, you found it in books. Sometimes, you found it in music. And sometimes, when everyone wasn’t really looking, you found it in the streets, in football.

If you were a scrawny middle-class kid in such a city at such a time, you went to a good school, spoke good English, got good marks. You came out at the other end the kind of kid people think of as a swot. Not the kind of kid people expect to see out in the dusty neighbourhood field, kicking a ball around with the kids your parents ask you to stay away from.

It doesn’t matter to them that this love of football is first nurtured at home, your dad waking you up at 6 a.m. in July of 1996, fast-driving to his clinic to watch the national team beat Brazil in the Olympic semi-finals. There you are, surrounded by clinic staff, hunched over a 21-inch coloured TV, yelling at the tube, celebrating the two extra-time goals that take the team to the finals in Atlanta, hugging strangers dressed in light-blue scrubs. You will repeat this experience multiple times in the decades to come, because in this city, in this country, football is in the air you breathe and the water you drink. It is an inescapable escape.

When, like many young kids from such a city and such times, you graduate from watching the game to casually playing it, it will baffle you that this comes as a surprise to many. Surely, they understand that football is not just the sport? For you, this is a lifeline, a light at the end of the tunnel when all else is bleak. It’s the thing you reach for when all else is pliable, a mainstay in the ship on which you sail through life. And more than anything, it is a constant. No matter where and how you play it—bare-legged in the dusty playground with a soft, hand-made ball, or fully kitted on a professionally maintained turf—some things about it never change.

One of those things is the sound—thunk—the ball makes when struck.

If you’ve witnessed the game enough, it becomes a sound you recognize anywhere—on TV, in a video game, listening to an ongoing match within earshot. Thunk. That sound of the ball striking (or being struck by) the foot, the head, the goalkeeper’s hands, the goal frame—especially the goal frame—is best experienced by hearing alone. So, if you’ll indulge me for a moment, imagine it with me.

Thunk. Player angles their body, contorts the hip, extends the leg. Thunk. Ball sails with the wind, arcs, all the power and velocity and beauty of gravity and physics. Thunk. Ball strikes the goal frame, the singular piece of iron on the pitch. Thunk. A header. Thunk. Goalie punch. Thunk. Long pass. Thunk. Shot. Thunk. Thunk. Thunk.

Not all thunks are made equal. In a way—and at the risk of sounding like a football purist—some thunks are more equal than others. If we were to roughly split them between ball-meets-body and body-meets-ball, we could attempt to pinpoint the purest, most recognizable form of thunk. In the former category, we may say that the ball striking the goal frame might be the quintessential example, one sure to raise adrenaline, draw collective oohs from a crowd, foster neverending replay reels. In the latter category, we could pinpoint the most iconic version—and arguably the purest form of thunk there is—as when a player takes a shot by striking the ball with their foot.

There is an undeniable beauty and a certain artistry that governs the football shot, depending on what part of the foot is used to hit the ball (instep, laces, toe poke, outside foot), the motion used to strike the ball to control flight pattern (straight shot, curve ball, knuckle shot, outside foot), how the shot is directed and directioned (lob, volley, top bins), how hard or soft the shot is, the distance from which the shot is taken. Professional commentators and pundits will often refer to the foot, when used in this myriad of ways, as a “wand”. Apt because, truly, magic is performed each time.

From playground recreation to professional game, one constant is the thunk of a football shot. Ferenc Puskás, the player after which the annual global award for best football goal is named, was dubbed Cañoncito Pum! by Spanish fans. Cañoncito loosely translates to Little Canon, referring to his left shooting foot. The pum!, an onomatopoeia that transcends language, is there to add heft in conveying the sound of his shots.

Pum! Boom! Thunk! In every language, on every field, the experience is the same—foot meets leather, sends it in a straight line or levitating arc. In the sublime moment where the ball becomes weightless before it drops, you witness and understand gravity, airflow, light, how they touch and caress this body as it floats. You understand space, time, orbit, earth, how small we are in this moment of grander things.

Say our scrawny kid from before grows up, sails on life’s ship—on which football remains a mainstay—and ends up elsewhere in the world. Say his ship has sailed through some of the rockiest storms in history, battered and beaten, arriving in the most vulnerable of states it has ever been. And like any good sailor, this former kid bears the scars of these travails, every nick and wound—of the body, of the mind, of the soul—imprinted upon him.

Say the world is not much different now than in that small city in the 90s, perhaps even worse—a health pandemic, a sociopolitical pandemic, an economic upheaval. Once again, this man understands that in order to survive, he will need to grow like a weed, finding light and succor wherever he can. Once again, he will look to his favoured lifeline, football (called soccer up in this Great White North, where his ship has docked, and where, luckily, there is a vibrant football community).

On his first visit to a pickup game at a local high school, he walks. Amidst the warring storms in his mind, as he nears, a familiar sound pierces the fog. It’s not just the voices of strangers-become-teammates calling to one another on the pitch—Here! Line! Shoot!—or the scuff of cleats on artificial turf, or the grunts and puffs borne of the athletic demands of the game. Not the scrape of the ball when it rustles in the net after a goal scored, like fish tussling in a catch. No, the thing he first recognizes, the line he latches on to and holds on for dear life, the line with which he pulls himself out of this drowning fog, is the thunk.

For the next few decades, he will hold on to the thunk. He will slowly return to regularly playing the game after years of absence, developing camaraderie with multiple teams, finding joy and light when all else is dark, until his body can no longer weather the demands. And even thereafter, he will remain close to the thunk, the sound that shocks him awake when he drifts, when the world tilts and he needs a mainstay to grasp. He will cling to the thunk, and for as long as he can hold on, it will keep him present and alive.

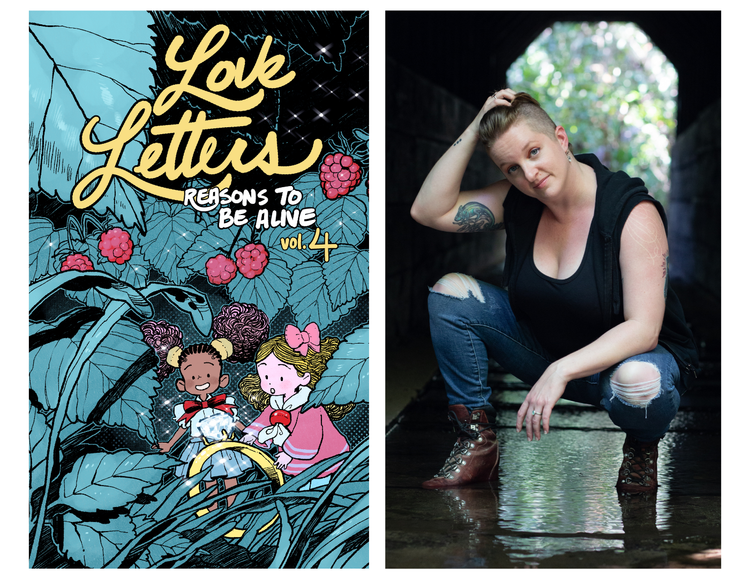

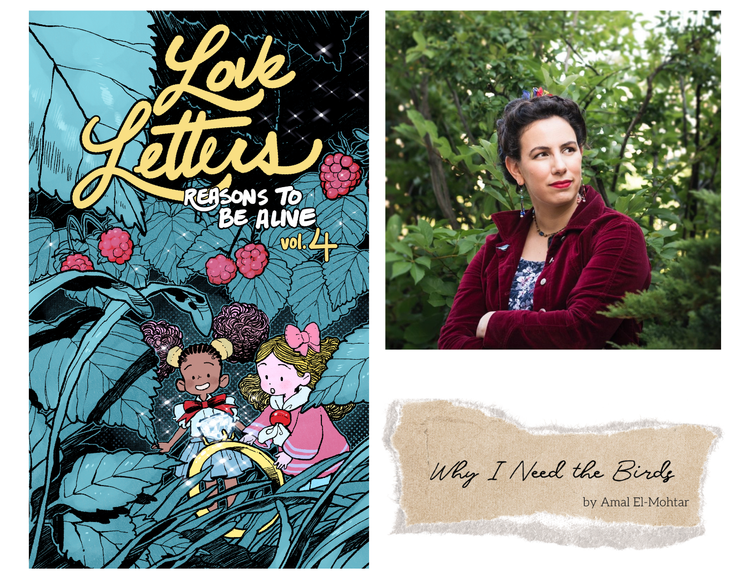

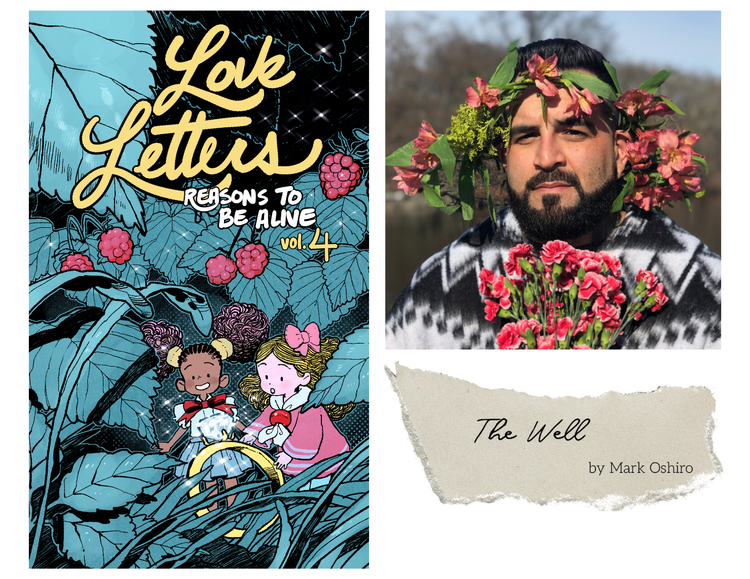

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion