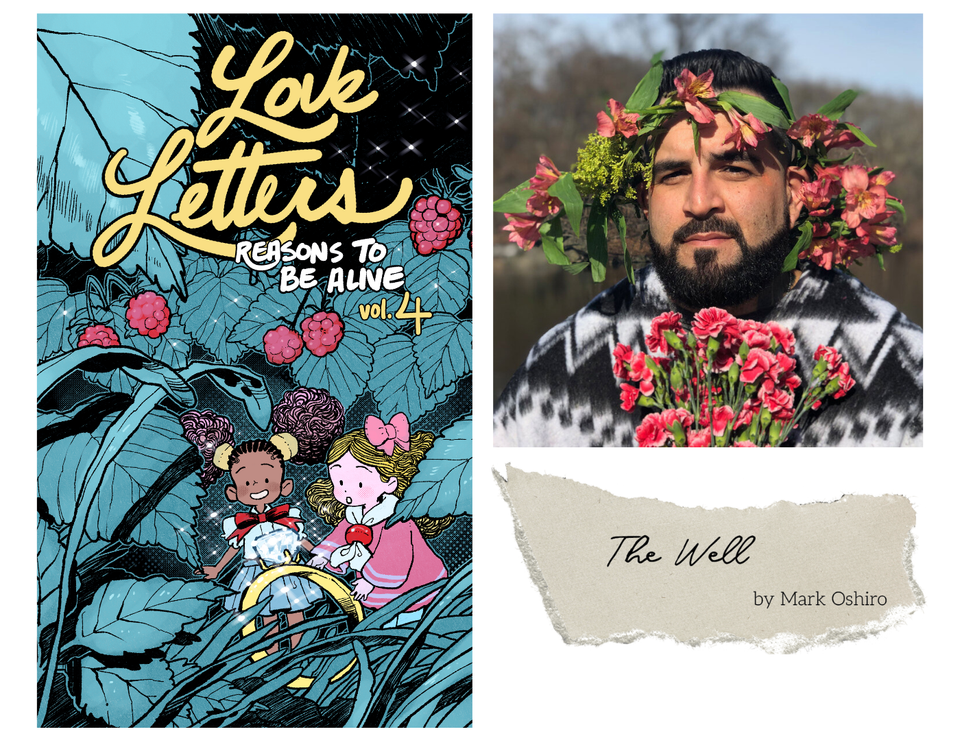

The Well

Mark Oshiro (they/them) is the award-winning author of the young adult books Anger Is A Gift (2019 Schneider Family Book Award), EAch Of Us A Desert, and Into The Light, as well as their middle grade books The Insiders, You Only Live Once, David Bravo, Star Wars Hunters: Battle For The Arena, and Jasmine Is Haunted. They are also the co-author (with Rick Riordan) of the #1 New York Times Bestseller and #1 Indie Bestseller The Sun And The Star: A Nico Di Angelo Adventure. When not writing, they are trying to pet every dog in the world.

This is a love letter to my ever-growing well of spite.

꘏

The well was empty for a small part of my childhood. I could have dropped a small stone into the well, heard a plink as it hit the sides, then marveled at the echo that returned back to me. I don’t know that there is a single moment I could pinpoint where I noticed it was filling up. Too many small ones, thimble-fulls of water that boiled under the surface of my skin.

Perhaps it was when my younger sister, adopted four years after my twin brother and I, arrived and got her own room. It was an instantaneous change. We were crammed into a single room, expected to take up half the amount of space we once did. It also came with the constant assumption that we were each half of a single unit of a person. Or maybe what started it all was having an identical sibling who was treated as the superior version of me, because he didn’t have a limp wrist and didn’t want to spend all day reading, and all the girls thought he was so very, very handsome.

Maybe it was then that I would have noticed that if I dropped a stone in that well, I’d hear a splash for the first time.

꘏

I was raised between a rock and a hard place: The rock was whiteness from my adoptive mother, and the hard place was the inaccurate model minority myth from the Japanese side of my adoptive father’s family. My relatives and those who knew my father held me to an exacting standard that was deeply unfair: I might not be Asian, but my brother and I had a certain degree of respectability and success that was required of us. On the other side, my mother’s whiteness amounted to a sea of rejection and delusion. Her reasons for adopting two Latinx boys were complicated and contradictory. She thought she could save us from a life of crime and drugs, but routinely told us we’d never amount to anything. Our skin color guaranteed that.

Functionally, I was never good enough for either of them, despite the fact that until one semester of an AP Physics class in my senior year of high school, I never received anything but perfect grades. My childhood was one gigantic trial of cognitive dissonance, and you know what that made me?

Pissed off. All. The. Time.

The well grew, but I didn’t dip into it until I was in eighth grade. My English teacher encouraged me to join a fiction competition for young people that was held in a nearby city. It was the first time an educator convinced my strict mother to let me attend an event outside of school without her participation. I can’t remember that teacher’s name, but I remember the small hatchback that pulled up outside my home. I remember the stories she told me about driving on the Autobahn and how bad American drivers were. I remember her sitting with me when the competition’s flash fiction theme was handed out, her hand on my shoulder. She squeezed it. I had never been touched like that before: affectionate, supportive, encouraging.

The emcee told us we had sixty minutes to write about embarrassment, and my teacher left the room. But not before uttering a particular set of words I’d not heard before:

I believe in you.

I lowered a bucket into the well. I pulled it up. And I drank from it. Because even at twelve years old, without the language to understand what I was feeling, I knew I should not have waited this long to have someone believe in me like that. The anger fueled me, and I wrote an ironic thriller about a young kid having to face his fear of public speaking. It was metafictional: He’d been assigned a speech about feeling embarrassed at one point in his life, and I drew out his terror of not knowing how he’d actually do it. And then, on his way up to the front of the class, he accidentally tripped on an untied shoe and face-planted onto the tile.

It was a huge risk, and I knew it while writing it, but I didn’t care. That teacher… she believed in me, and I deserved to hear that before this moment.

The words flew out of me. I turned it in with ten minutes to spare.

I won first place.

When I showed my mother the certificate and the check for the prize money, she tore them up. She said I’d never be a writer, never would make any money from that type of career, so I better give it up now.

꘏

I didn’t.

꘏

She would do that to me again and again: allow me to pursue a goal related to writing, then denigrate it after I did well. And each time, my well of spite grew. When she kicked me out of our home at sixteen, my initial horror over what had been done to me turned into an invigorating motivation. If I wasn’t going to have my parents’ support, then I was going to get what I wanted by myself.

It’s been almost exactly twenty-five years from that pivotal moment, and in those years, the well continued to grow deeper and fuller. When my college creative writing professor told me that no one wanted to read about “you people,” I dipped into the well. When peers told me that I was too old to debut as an author, I dipped into the well. When an editor told me that they didn’t know how to sell my book to “normal people,” I… well, you know.

I drank from that fucking well.

꘏

There is a thirst that comes with feeling ignored, betrayed, disrespected, unappreciated. I grew up with a parched throat, and nothing has quenched me greater than all that spite. It is a renewable resource, a perpetual motion machine that always has something to give me. Spite is an act of self-love: If others will not provide for me, then I’ll provide for myself.

Alchemical. Transcendent. Loving.

And very, very much alive.

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion