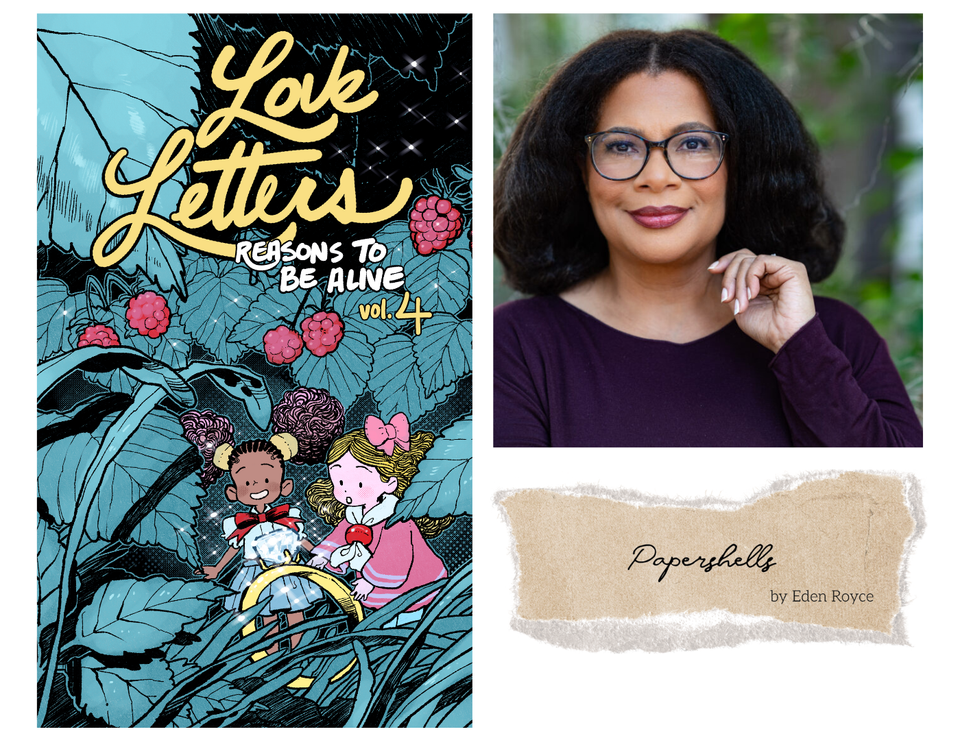

Papershells

Eden Royce is a writer from Charleston, South Carolina. She’s a Shirley Jackson Award finalist and her short stories and articles have appeared in a variety of print and online publications. Her debut novel Root Magic is a Walter Dean Myers Award Honoree, a Nebula Award Finalist, an Ignyte Award winner, and a Mythopoeic Fantasy Award winner for outstanding children’s literature.

There’s a saying where I’m from–a small Freshwater Geechee community in Charleston, South Carolina–that I find particularly evocative and pointedly insulting. It goes something like this:

You the kinda person who ain’t never had to pick up pecans out the yard for your gramma, and it shows.

Now what that means exactly is untranslatable, but suffice it to say, if you know, you know.

No one can accuse me of being that kind of person. I picked up pecans from our backyard and yes, it was on the instruction of my grandmother. While she has since passed away, I still have vivid memories of her handing me an empty plastic container that had once held pineapple sherbet and telling me to fill it up.

Our backyard was a menagerie of growing, edible plant life. Bold round flowering garlic heads like giant dandelions. A fig tree that required us to fight off the blue jays at the crack of dawn for the ripest selections. Wild vines of blackberries that were worth braving the thorns. And ropy vines of deep yellow honeysuckle flowers that gave the perfect drop of sweet nectar when you pulled the stamen. All of it growing wild and in addition to whatever we’d planted that year.

The grand dame of all of that wild harvest was our pecan tree. It stood smack dab in the middle of it all, a matriarch watching over her descendants, holding herself proud and tall. That tree had been there for as long as I could remember. As long as my mother could remember, even.

I would look up and barely be able to see the top of its branches. But I’d run to it just the same and pick up the nuts littering the ground at its base. Those elliptical-shaped nuts, a warm brown I associate with smiles and laughter, littered the ground like candies thrown from a parade float. I happily gathered them, and dropped them into the plastic container, knowing what was to come.

Pecan trees are native to the United States, and the word “pecan”–no matter how you pronounce it–derives from several Algonquin languages, the closest of which to where I grew up uses the word “paka’n” meaning “requires a stone to break.” Most pecans do require a stone or a mallet or a nutcracker to break the tough housing containing the edible nut inside. Papershell varieties have a unique feature that I loved as a kid. Their protective shells are thinner, eliminating the need for a nutcracker, hammer, or stone.

As a kid, I could place two of the nuts in their shells in my cupped palm, place my other hand on top, and press just the right way. That satisfying crack that resulted meant I had time to enjoy a few of the sweet pecan halves I pulled from the bitter shells before filling the container. It was a special treat to lean up against that rough bark, against that supportive trunk, shielded from the white-hot rays of the Carolina sun under its leafy canopy. It was a prize worth savoring.

While I wasn’t taught this in school, I researched pecan trees in the library and learned the first recorded grafting technique of pecans was accomplished by an enslaved gardener named Antoine from an area near New Orleans. He grafted a superior wild pecan to seedling pecan rootstocks. This clone was named “Centennial.” Mr. Antoine’s planting of 126 Centennial trees was the first official recorded planting of cultivated pecans. As a descendant of enslaved people myself, I felt a connection to Mr. Antoine and his efforts. I wondered if he ever got the chance to pick up pecan nuts himself and eat them with any freedom.

I read recently that of all the nuts we consume as nut meat and as alternative milks (almond, cashew, etc.), the pecan is one of the only ones that thrives in quantity without the need for added irrigation, making it more cost-effective and more sustainable than its needier counterparts. Pecan trees exist on rainwater, however much or little they may get and still provide one of the sweetest, softest nuts.

Back then, on those days I gathered pecans from our yard for my grandmother, I noticed how they fueled my imagination. In my small, seven-year-old fingers, a pecan fit like a writing utensil. The sharply pointed tip of each shell became, in my mind, a pen nib. Sometimes, the pecans would have a splash of black coloring around that sharp end, adding to my child-like fantasies of writing with a fancy fountain pen. Its color, a perfect brown, dotted with tiny freckles, reminded me of my mother’s ankle–the only part of her that I could see when I sat on the floor while she braided my hair.

Once the sherbet container was full, I’d scurry back inside. Then grandma would spread newspaper over the bar in the kitchen. Over cups of hot or iced tea, my grandmother, mother and I would sit and crack the pecan in our palms, artfully removing the halves in one whole piece and quickly devouring the one that fractured. We told stories of what life was like for our people, a mixture of sweet joy and bitter experience, but we would have to take those bitter shells, like the ones in our palms, scattered on the table amongst the newsprint and pluck out the sweet, tender bits and keep them close.

We filled plastic zipper bags that way, laughing and sharing as people came in and out of the house, giving and taking, leaving their stories at the table and in my ears. Rejoicing in being us. Radio playing, back door bell chiming, pots bubbling on the stove. Plucking the sweet from the bitter. Cracking through the outer shell of life to feast on the tender bits.

Whenever I think of pecans, I think of my people’s experience in the United States. My Gullah Geechee people and all of the enslaved Black people, including Mr. Antoine. Taking what little may have been given to us, and nestling it close, nurturing it, giving it a hard shell to protect our natural softness and sweetness from the harsh scarcity of the world.

And I think of how we still manage to thrive, finding joy in our lives, no matter how much or how little rain might fall. And I think of my grandmother and that plastic pineapple sherbet container, and how in my heart, they are both always there, full of papershells.

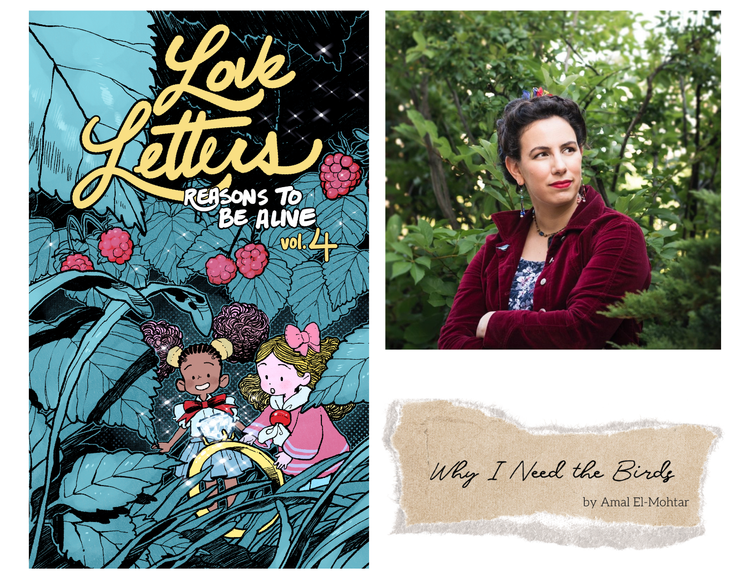

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion