On Magic in Political Art, and Magic as Political Art

Elijah Kinch Spector is a novelist and dandy who was raised in the Bay Area counterculture and now lives in Brooklyn. He is a British Fantasy Award finalist whose writing has received acclaim from NPR, Nerds of a Feather, Reactor, Foreword, and Paste Magazine, among others.

Sometimes writing overtly political books can feel painful and useless. Like, how much difference is one more leftist SFF novel going to make?

A few years ago, with exactly these thoughts in mind, I read a 1959 book called The Necessity of Art: A Marxist Approach. Instead of providing artistic clarity, it inspired the curse magic in my fantasy novel.

Early in The Necessity of Art, Ernst Fischer argues that (emphasis his) “art in its origins was magic.” Early humans developed ritualistic ways of understanding and controlling their world, which were eventually split off and categorized into either “magic” or “art.” It probably isn’t the best science, but it’s a fun idea!

While making a point about the power of imitation, Fischer cites a 20th century attempt to curse someone with a deadly illness on the island of Dobu, in Papua New Guinea. To enact his curse, the “sorcerer” must imitate the gruesome death he hopes to inflict. He screams and writhes on the ground while describing his enemy’s destruction not by disease, but by the beak of a hornbill:

he cuts, he cuts,

he rends open,

from the nose,

from the temples,

from the throat,

from the hip…

And on down the body. Fischer makes no moral judgments, and he respects the ritual and its artistry, but he also absolutely portrays this 20th century practice as a window onto the ways of “early man.” Which is bad, but still somehow better than what he’s quoting: Ruth Benedict’s 1934 book Patterns of Culture, which calls the people of Dobu “lawless and treacherous.”

Not a great source, then. Even so, the image of touching one’s enemies through imitating them really lodged itself in my head.

Soon after, I came across strikingly similar magic in S. Ansky’s 1912 story “The Rebbe of Apte and Tsar Nicholas I,” collected in the anthology Radiant Days, Haunted Nights: Great Tales from the Treasury of Yiddish Folk Literature. Around the time he wrote the story, Ansky had returned to the Jewish Pale of Settlement, where he’d been born and raised, to do ethnographic work on local customs and folklore. One way he disseminated what he’d learned was through fiction.

In the story, a rabbi tries to use magic to stop Tsar Nicholas I of Russia from signing three anti-Jewish edicts. To do this, he has a throne made in the synagogue, where he installs his “pseudo-tsar”—a man born on the same day and at the same time as the real thing—in fake finery and a paper crown, flanked by “guards” drawn from the congregation.

The rabbi convinces the pseudo-tsar to rip up two of the edicts, before the pseudo-tsar flies into an antisemitic rage and begins to beat him. This causes the paper crown to fall off, ending the performance immediately. The man who was playing the tsar doesn’t remember a thing, and “upon hearing that he had cursed and struck the rebbe, he burst into tears.”

The spell works, and we’re told the real Nicholas I ripped up two of his edicts, but that the third still went into effect. Even in a fantasy of controlling the tsar, with a price paid in physical violence, victory isn’t complete.

Now we have these two rituals, each from different cultures and retold by a crew of unreliable narrators (including me). In both cases, painstaking artifice is used to imitate an enemy who may not even be affected by the spell. The caster, however, will be hurt either way. Maybe Fischer was right, and magic is art.

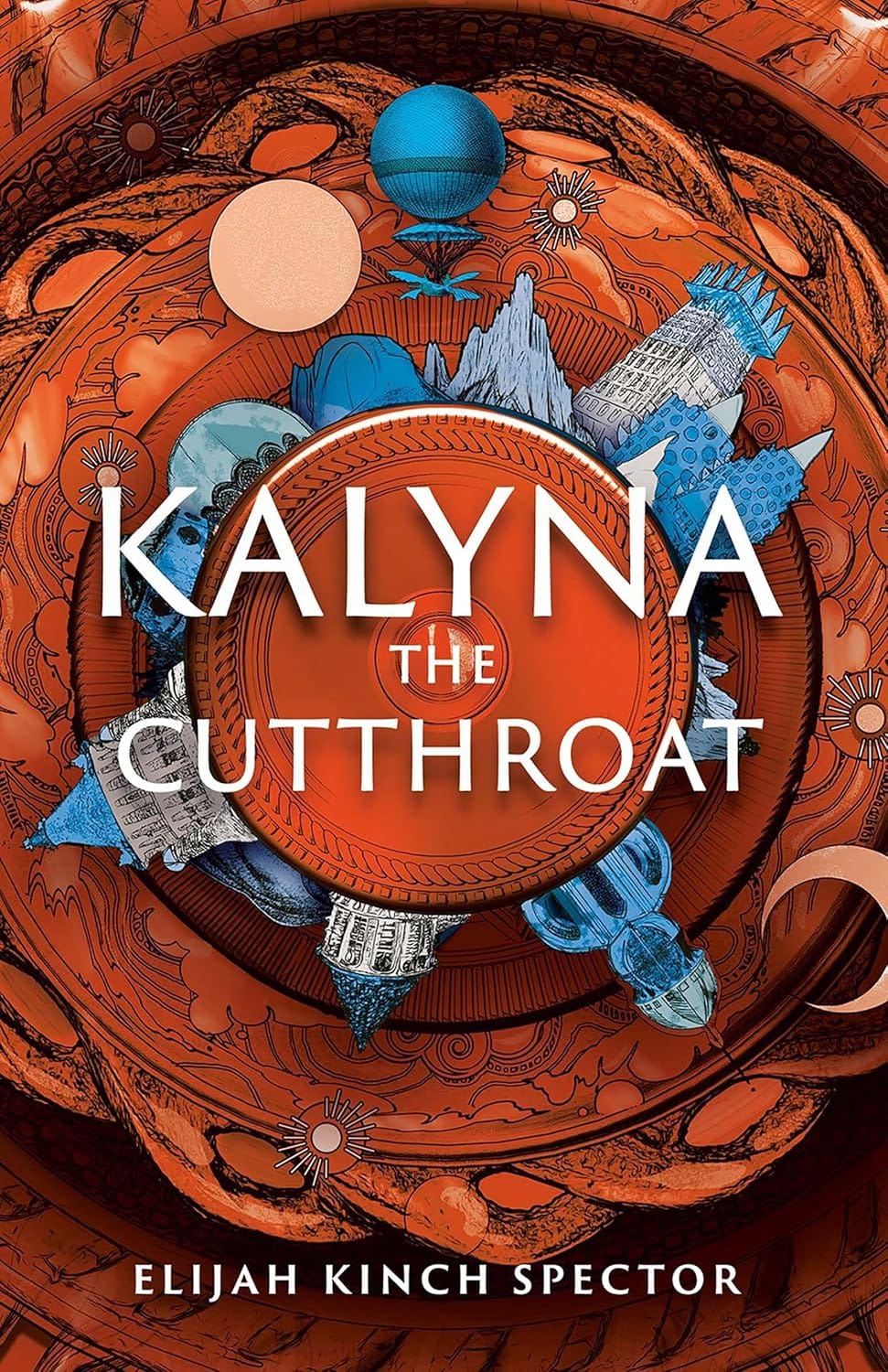

So, my new book, Kalyna the Cutthroat, is partly about ethnic cleansing, genocide, refugee crises, and who gets left out of a petty bigot’s national project. And I tell you, having it come out in November of 2024 kinda felt like spending the two hardest years of my life gathering up enough saliva to spit into the wind.

Of course James Baldwin has a more beautiful thought on the matter, relayed in a New York Times interview in 1979:

The bottom line is this: You write in order to change the world, knowing perfectly well that you probably can’t, but also knowing that literature is indispensable to the world. The world changes according to the way people see it, and if you alter, even by a millimeter, the way people look at reality, then you can change it.

It’s true. But all that work for a millimeter can feel demoralizing.

I don’t know what role community played in the magic practiced on Dobu in the early 20th century, because Ernst Fischer got Ruth Benedict’s version. And her view of the people of Dobu as individualistic and treacherous wielders of curses came from the 1932 book Sorcerers of Dobu, by a man with, I’m sorry, the most colonizer name ever: Reo Fortune.

While there was a paternalistic side to S. Ansky’s ethnographies, the people in “The Rebbe of Apte…” get a much more sympathetic narrator, one who shows them working their magic on the tsar as a community. Why, you could even call it collective action! Which requires collective imagination.

That’s at least one answer to the question of leftist art right now: trying to expand the collective imagination and recognizing that you’re working with others to do so, even if your artistic practice is solitary. Enough of Baldwin’s “millimeters” together can add up to, well, a centimeter.

Kalyna the Cutthroat is also partly about mutual aid, so I was delighted to include magic that could only be cast by a community. But I didn’t use it to change the villain’s mind. Because our collective imagination doesn’t deserve two out of three.

Kalyna the Cutthroat by Elijah Kinch Spector

Radiant Basket of Rainbow Shells, scholar of curses and magical history, has spent several years on a research expedition abroad in Quruscan, one of the four kingdoms of theTetrarchia. When Tetrarchia and Radiant’s home country of Loasht suddenly revoke their tenuous peace, Quruscan is no longer the safe haven for Radiant that it once was. He needs someone to help him escape: a bodyguard, perhaps, or someone with the sheer cunning to escort him to safety. The perfect candidate is Kalyna Aljosanova: a crafty, mysterious mercenary with an uncanny reputation.

But the political situation in Loasht is far more volatile and dangerous than Radiant left it; it soon becomes clear that he may never be able to return home to his family. With a little of Kalyna’s signature guile, she finds Radiant asylum in a utopian community on the border between Loasht and the Tetrarchia, and, for a moment, it seems like they might finally have a safe place to stay. But when the group’s charismatic leader grows wary of the refugees flocking to his community—and suspicious of Kalyna in particular—that sense of safety begins to unravel once more.

Kalyna the Cutthroat deftly imagines how the pressures of heroism can warp even the most unshakeable of survivors, asking what responsibilities human beings have to one another, and whether one good deed—of any magnitude—can absolve you of your past for the sake of a future.

Barnes & Noble | Bad River Website | Local Library | Find an Indie Bookstore

Member discussion