Read Like a Criminal

This past week, I was delighted to participate in the Ann Arbor District Library's annual Big Gay Read festival. My novella Upright Women Wanted was selected as the featured book, and AADL invited me to come to Ann Arbor to give a talk to close out the festival. I was thrilled at the opportunity (anything for a chance to show up at a library).

After an adventurous journey to Ann Arbor that included many flight delays, a wedding, a flooded rental house, a defunct ferry, a thirteen-hour drive, and an idyllic afternoon in a blueberry patch – I arrived in Ann Arbor, speech in hand, exhausted. I went to sleep in a hotel room around the corner from the library branch where I was due to give my talk the next day... and I woke up somehow even more exhausted.

And feverish.

Turns out COVID had finally caught up to me. I called the events team at AADL the moment I saw the positive test result. (Well, okay, after a solid minute or two of swearing). They immediately sprang into action, pivoting my talk to Zoom with less than an hour before we were due to go live. They handled the crisis brilliantly and were kind, patient, and thoughtful at every single step of the way. I'd expect nothing less from librarians, but still: I was and remain overwhelmingly grateful for their speed, precision, and care.

So, here it is! The full text of my talk, with selected slides. There's also a video of the talk. You can watch or listen to it if you'd like to see all the slides, or if you'd like to watch my fever slowly but surely spike over the course of the hour. (Or if you want to see the large painting of Gillian Anderson harvesting marshmallows that was in my hotel room, behind me, throughout my entire talk.)

You'll notice a few differences between the text of my talk and the content of the video – namely, the fact that all my references to being "here in this room together" with the audience are now moot. But really, we are all in the same world together, so the points still stand. I may be in quarantine, but I'm with you, friends.

Read Like A Criminal

for Ann Arbor District Library

Hello, friends. I’m Sarah Gailey, author of Upright Women Wanted, which is about living under an authoritarian regime that achieves its goals by deprioritizing public and social services, leaving people to largely fend for themselves, while tightly controlling what media and literature they have access to.

When people ask me how I went about building the world of Upright Women Wanted, I always tell them the same thing: I took a close look at how existing and historical fascist regimes treated the people who lived within them, and I saw the future that many people in power want for this country. I wrote about that future–a future in which the government prioritizes the consolidation of wealth and power, corporate profit, and imperial expansion at the expense of the material, physical, and social needs of citizens using violence and strict control of information to pursue those goals and enforce compliance.

It’s vital to understand that there is a direct relationship between state-inflicted violence and state-governed control of information. Tonight, we’re going to take a closer look at that relationship, so we can come to a shared understanding of the purpose of authoritarian media censorship–and the necessity of learning to identify oneself as a criminal in the eyes of the State.

Before I begin, I want to make sure you’re aware that tonight’s talk will include discussion and images of police activity and conditions of incarceration. I think this subject is worth your attention and time, but if this subject matter isn’t something you think you can engage with here and now, I’d encourage you to watch this talk at home online later instead, where you can attend to your physical and emotional needs safely.

To get a better understanding of authoritarian media censorship, we’re going to do exactly what I did when I was researching Upright Women Wanted: we’re going to look into history. But rather than looking at the history of Germany or Italy or Japan, we’ll be sticking a bit closer to home.

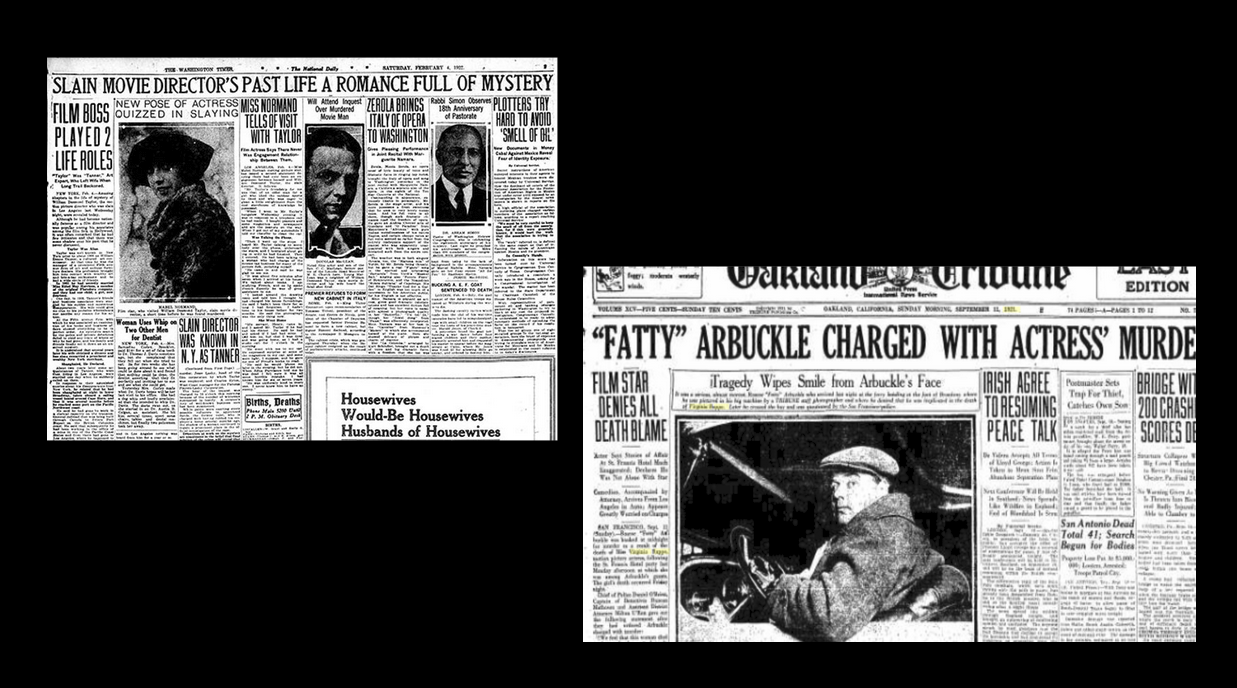

In the 1920s, the American film industry was in desperate need of image rehabilitation. This breaking point came along due to, among other things, the murder of silent film director William Desmond Taylor, and the trial of actor Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, who was accused of sexually assaulting and killing Virginia Rappe. Although we can’t know the actual events of the night that led to Rappe’s death, the accusations and trial were unquestionably motivated and driven both by intense fatphobia directed at Arbuckle himself… and by a popular perception of Hollywood as debauched and immoral.

Prior to this in 1915, the United States Supreme Court had already unanimously ruled, in Mutual Film Corporation v Industrial Commission of Ohio that motion pictures did not qualify for free speech protections. The decision states that, quote:

“However missionary of opinion films are or may become, however educational or entertaining… they may be used for evil… Their power of amusement, and, it may be, education, the audiences they assemble, not of women alone nor of men alone, but together, not of adults only, but of children, make them the more insidious in corruption by a pretense of worthy purpose or if they should degenerate from worthy purpose.”

As a result, individual state governments imposed censorship on all film and cinema. They leveraged fees and fines for those who failed to comply with their new standards–but, notably, they did not publish or share those standards–so film producers had no way of knowing if their work was compliant until they started encountering consequences.

After a few years of dealing with this, Hollywood realized it needed to get ahead of state government censorship. It also wanted to ward off the looming promise of federal censorship–so, in 1922, Hollywood established the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America to manage a system of self-imposed censorship guidelines.

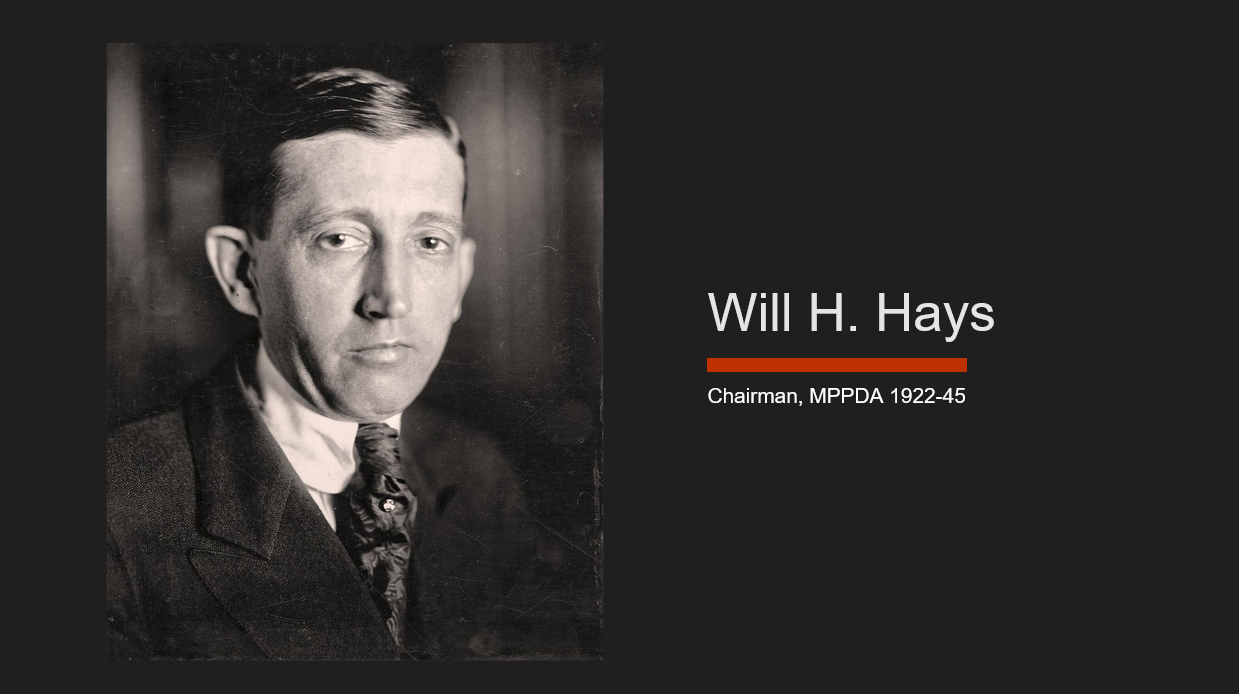

A man named Will H. Hays accepted the position of Chairman. This role would make him arguably one of the most influential figures in the history of American cinema.

Under Hays, the MPPDA steered Hollywood into a culture of pre-emptive compliance. This was a kind of compliance that Hays, alongside his colleagues Martin Quigley and Daniel Lord, were more than comfortable with. Together with several studio heads, those three led the process of creating a code that would define acceptable content in American cinema from 1934-1968. Although the Hays Code (as it was known) would be formally retired in the late 60s, the ripples caused by the code are with us in this room today.

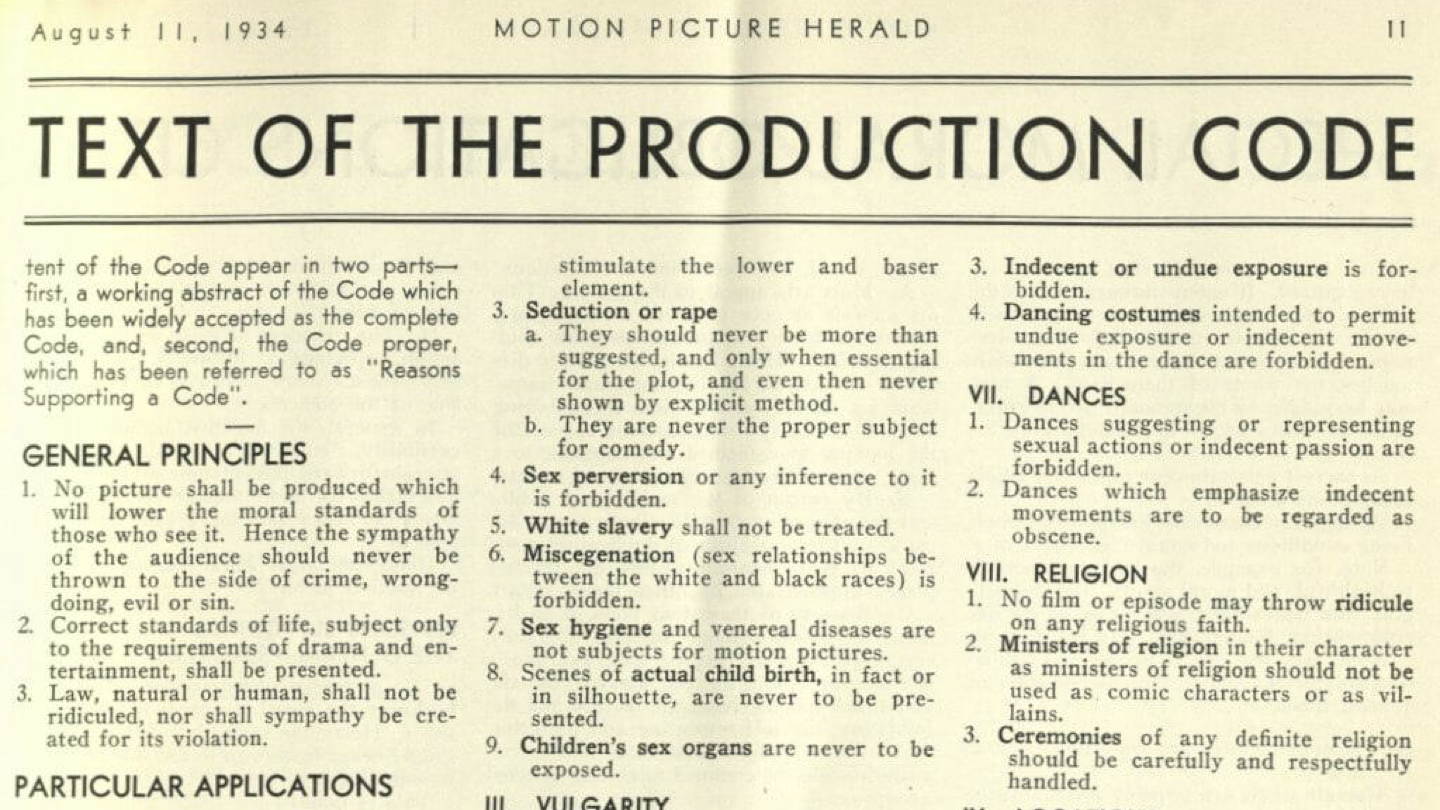

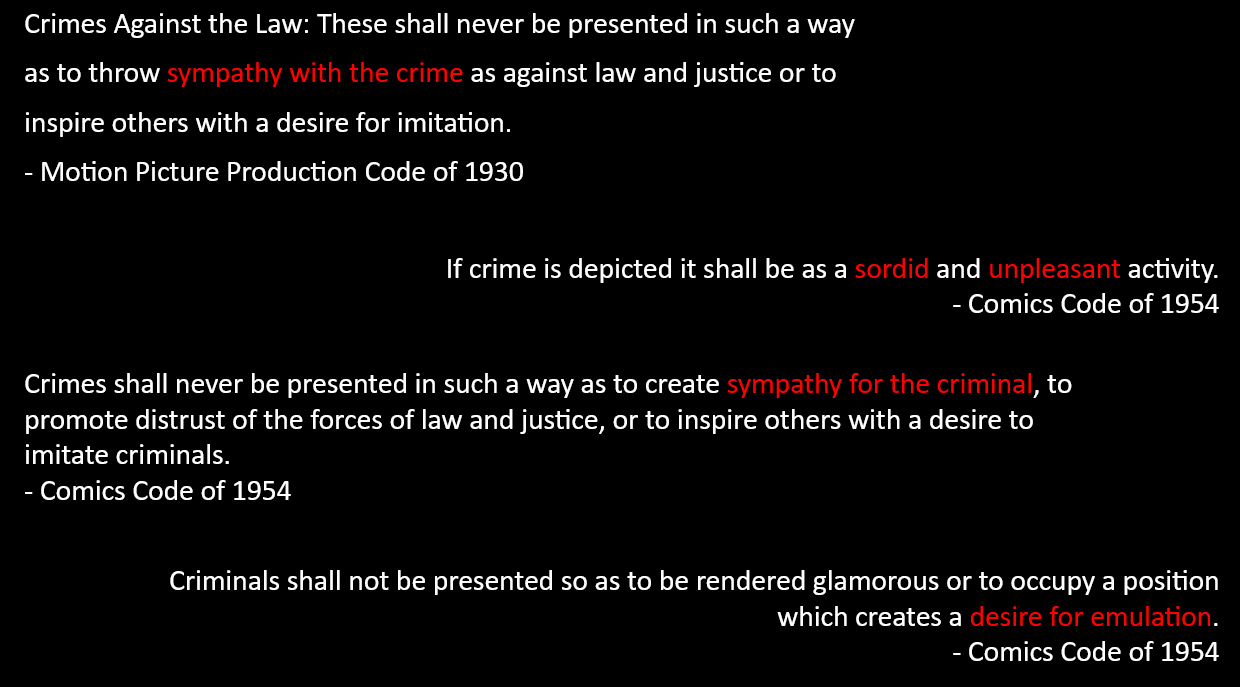

So what was the Hays Code? It went through several iterations, including a loose but effective lists of “Don’ts and Be Carefuls,” but here’s the version that lasted:

I won’t read this whole thing to you–we’d be here all night–but here are the general principles:

- No picture shall be produced that will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin.

- Correct standards of life, subject only to the requirements of drama and entertainment, shall be presented.

- Law, natural or human, shall not be ridiculed, nor shall sympathy be created for its violation.

Things get a lot more granular from there – notably:

- Crimes Against the Law: These shall never be presented in such a way as to throw sympathy with the crime as against law and justice or to inspire others with a desire for imitation.

- The sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld. Pictures shall not infer that low forms of sex relationship are the accepted or common thing.

- The treatment of low, disgusting, unpleasant, though not necessarily evil, subjects should always be subject to the dictates of good taste and a regard for the sensibilities of the audience.

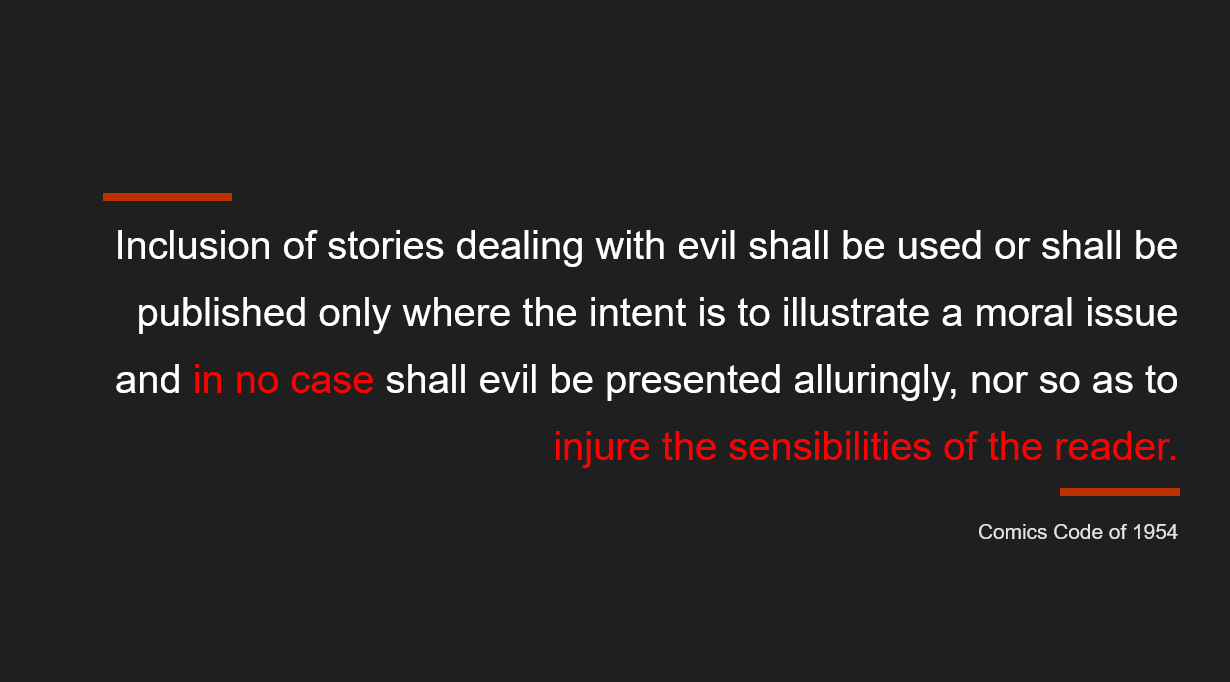

Those six principles have significantly defined American media for the past ninety years. There are undeniable parallels between the full content of the Hays Code and the content of a similar set of guidelines established in 1954 and written largely by Judge Charles F. Murphy on behalf of the Comics Magazine Association of America.

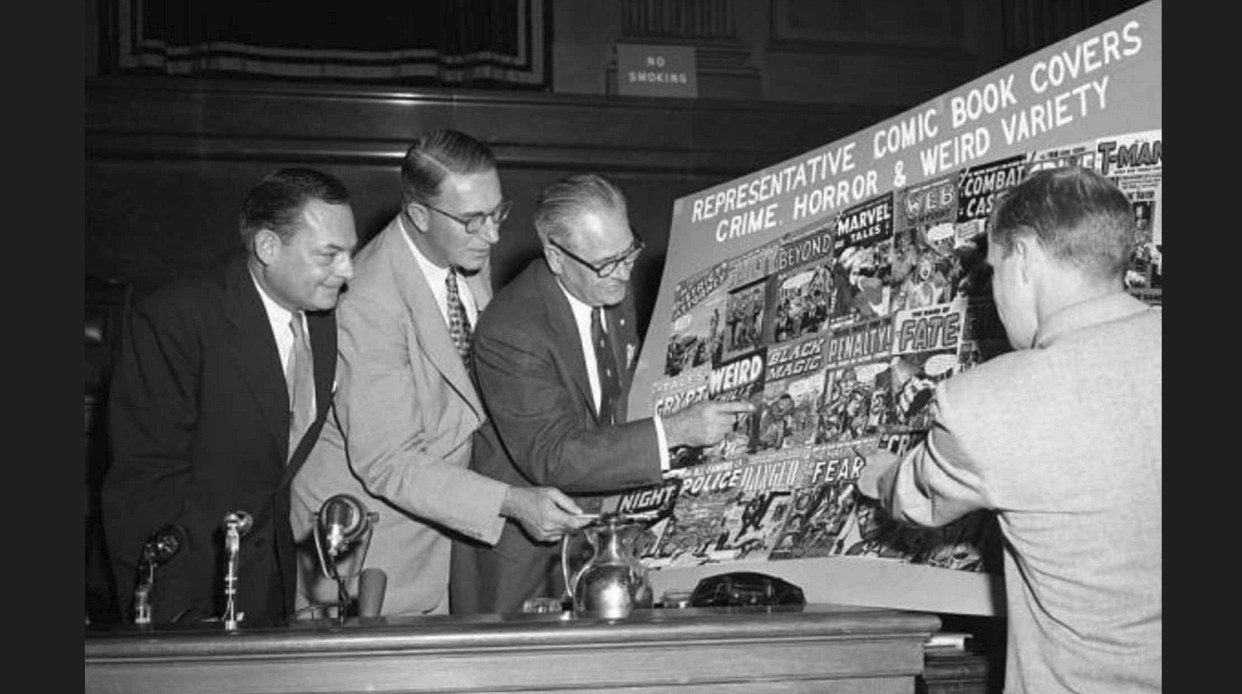

Like the Hays Code, this self-imposed industry-wide censorship effort developed in response to a moral panic of the era that was kicked into high gear by psychiatrist Fredric Wertham's book Seduction of the Innocent. The result of this moral panic was the attention of US Senator Estes Kefauver, who led a televised Senate hearing that targeted comics.

The result was the death of 15 comics publishing companies, and in response to this climate, the Comics Code was born.

The Comics Code generally discouraged sex, violence, gore, queerness, and just about any content that might bump the reader’s heart rate above 50 bpm. A few notable points from the code for our purposes here tonight:

- Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal, to promote distrust of the forces of law and justice, or to inspire others with a desire to imitate criminals.

- Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates a desire for emulation.

- Policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

- In every instance, good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

William Gaines, publisher of EC comics–a company that was heavily targeted by the language of the Comics Code and Senator Kefauver’s senate hearing–fought back against Murphy and the Code. One notable anecdote, which I can’t verify the specifics of but which is a legend of the comics industry, goes something like this:

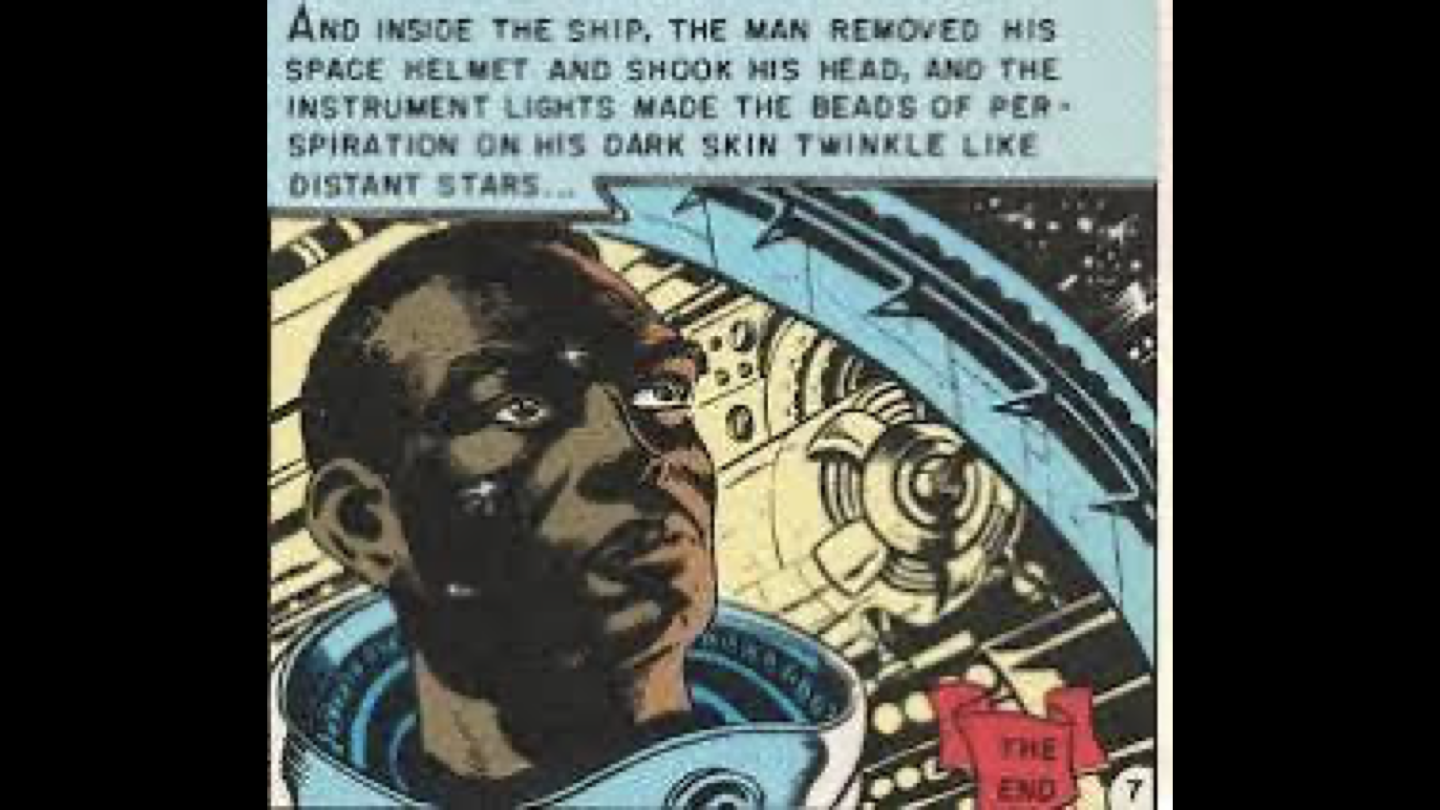

In 1953, Gaines attempted to publish a comic called “Eye for an Eye,” and was denied by the Comics Code Authority. He decided to print Judgment Day instead–a comic in which an astronaut visits a planet of robots, only to find that the robot society is structured around color-based discrimination. At the end of the comic, the astronaut is revealed to be Black.

Judge Charles F. Murphy instructed EC that the astronaut would need to be changed from Black to white. Gaines, the publisher of EC, pointed out that this type of requirement was nowhere in the code. When Murphy said “c’mon, you know you have to change this and you know why,” Gaines responded: “Ok, thanks for letting me know bestie!! I’ll just go ahead and go to the press and let them know what you’re making me do :3.” Murphy wound up giving the comic the necessary approval rather than risk the exchange going public–although of course, gossip networks wound up spreading the word anyway.

This is just one way in which creatives fought the censorship projects of the Comics Code and the Hays Code. They recognized, across industries, the dangers of these efforts–and they worked courageously to oppose censorship at every opportunity, just as we work to fight it today.

The similarities between the Hays Code and the Comics Code are not coincidental. Not only because one can see the lineage of inspiration between the two codes–Charles F. Murphy was inspired by both the Hays Code and the existing, unenforced code of the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers–but because they are working toward the same goals.

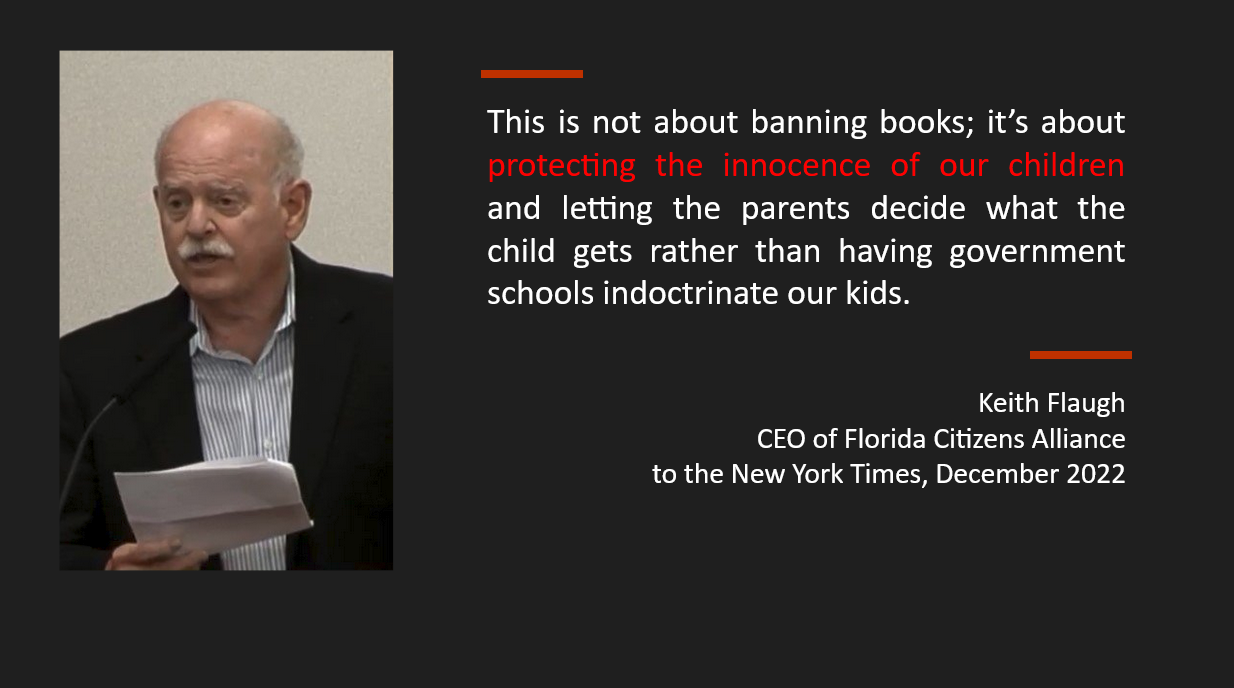

These are the goals supported by contemporary book banning efforts by groups that claim to be “protecting children” like Moms for Liberty and the Florida Citizens Alliance.

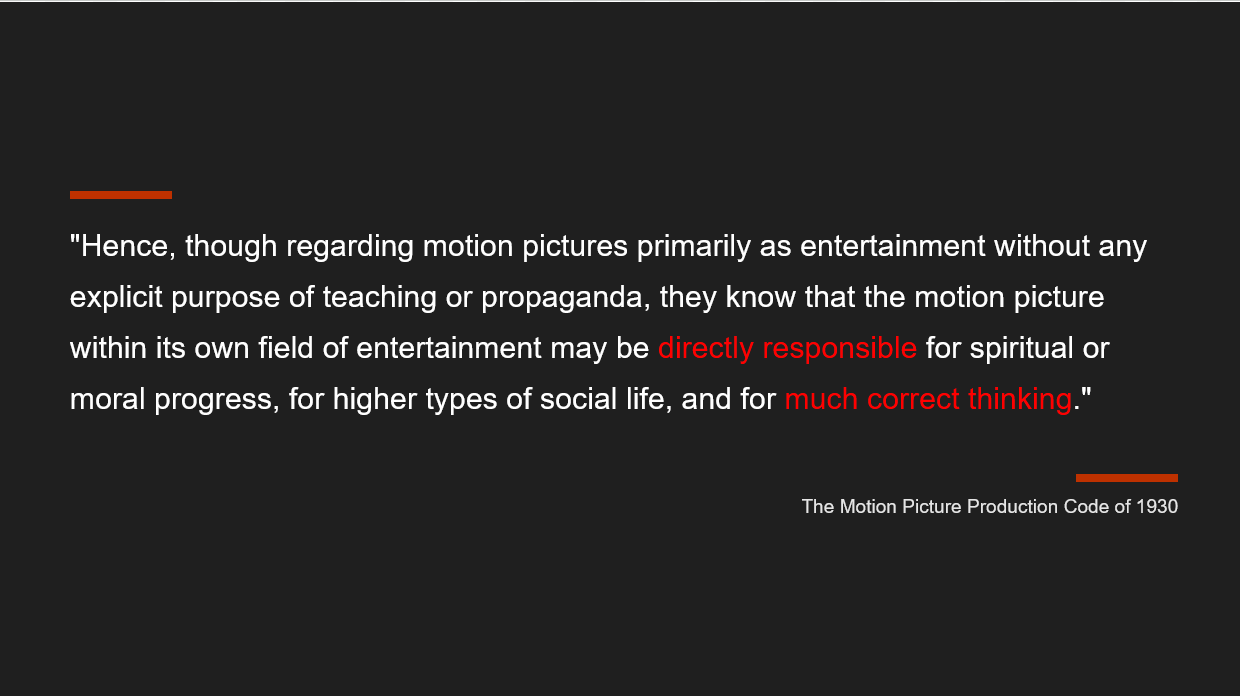

The immediate goal is control over what narratives people are exposed to. The terminal goal of that effort is control over people’s actions. The path from point A to point B is one of moral instruction: Using narrative limitation to change the way people think about what is or is not acceptable. We can see this explicitly outlined in the text of the Hays Code: “The motion picture within its own field of entertainment may be directly responsible for spiritual or moral progress, for higher types of social life, and for much correct thinking.”

By framing media as “directly responsible for spiritual or moral progress,” the Hays Code shifted the function of American cinema from entertainment to instruction. In compliance with this requirement, American media in general moved into a mode of telling viewers not only how to behave, but how to feel about what they are seeing. It is not enough for someone onscreen or in a book to be evil; we need to be told they are evil, and everyone is in agreement about their undesirability in the end.

The Hays Code imposed a violent standard of “moral purity” on media that has fundamentally shifted how we view ourselves, our history, our culture, and by extension, evil: The bad element must be obvious, malignant.

We, the viewers, must know with whom we are meant to agree; we must also know whom we are meant to abhor. This, per the ideals of the code, is how citizens learn to uphold society.

As a result of this educational approach to media, multiple generations of media consumers across various forms have become oriented towards uncritical consumption of the facets of media that are intended to instruct us on morality and personhood, which, by design, leads to the dehumanization of those who have been uncritically presented as inherently villainous.

The constant reinforcement of the notion that people can’t consume media without being instructed by it has led to an expectation of media as morally and ideologically instructive. As a result, we frequently anticipate, in our media and especially in our villains, a confirmation of what is good and what is bad.

And the archetype of a criminal is, overall and by default, according to the media and literary landscape we currently inhabit: Bad.

This returns us to the content of the Hays Code and Comics Code that focuses on criminals and criminality. Those two censorship codes put a lot of mustard on the way criminals are to be treated in “appropriate” media.

Why is that so important to a censorship effort? And–recalling that both censorship efforts were driven by pre-emptive compliance with anticipated federal censorship–why might this treatment of the “criminal” serve the interests of an oppressive state?

In order to get to the bottom of this, we have to dive into some specifics of terminology. First: What is a criminal?

Is a criminal someone who is evil? Is a criminal someone who causes harm? Not necessarily–in fact, those ideas are immaterial. A criminal is someone who breaks a law. It’s as simple as that. No person or object or property needs to come to harm in any way in order for a crime to occur, provided that a law is being broken. And by contrast, great harm can be perpetrated–without the perpetrators being labelled “criminals.”

And yet, when we talk about criminals in contemporary media, we tend to frame their actions as synonymous with “causing harm.” Even when the narrative is on the side of the criminal, the story tends to be clear that either the criminal is appealing in spite of being villainous–or the criminal is unique among criminals, and thus likable and redeemable.

This philosophy jumps out at us quite clearly in the Comics Code: “Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal. Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates a desire for emulation.” In narratives that follow these guidelines–guidelines that, across the Hays Code and the Comics Code, shaped American media for decades–crime and by extension criminals are, necessarily, bad. They are something different from you and I, from normal upstanding citizens.

This changes how we think it’s acceptable to treat criminals. The narratives we consume repeat, over and over again, that criminals can and should be treated differently than other people, because they are a different kind of creature.

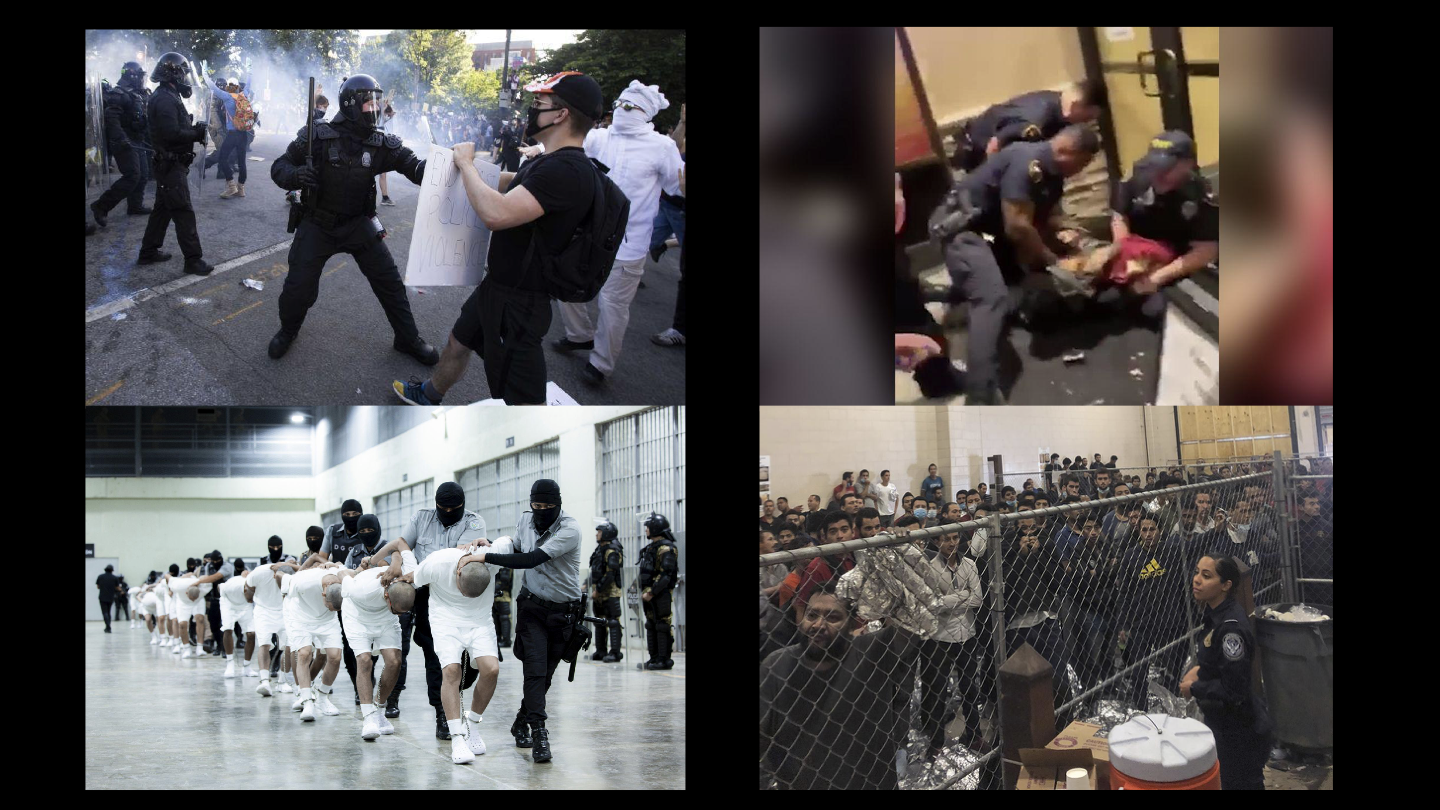

If we look at popular media, we see a reflection of how our society broadly thinks it’s ok to treat a criminal:

And if we look at real-life, we can get a window into how people we label as ‘criminals’ are treated day-to-day by the American police and detention system:

This treatment, both in media and in life, is a reflection of the conflation of the identity “criminal” with the identity “villain” - and with the identity “problem.” We thus end up identifying a “criminal” as “an element to be removed, for the improvement of society.”

This assumption then leads to us supporting and protecting the forces that promise to “remove” the undesirable element, even to the extent of enabling them to perpetrate harm without consequence.

So we can separate the concept of “harm” from the concept of “crime,” and we’ve established that a criminal is simply someone who breaks a law.

In that case, we must understand: What is a law? The great philosopher Brennan Lee Mulligan once said, “Laws are threats made by the dominant socioeconomic ethnic group in a given nation. It’s just the promise of violence that’s enacted.”

This is a perfectly succinct summary of a law: A promise of violence as consequence for any action that opposes the interests of that dominant socioeconomic ethnic group.

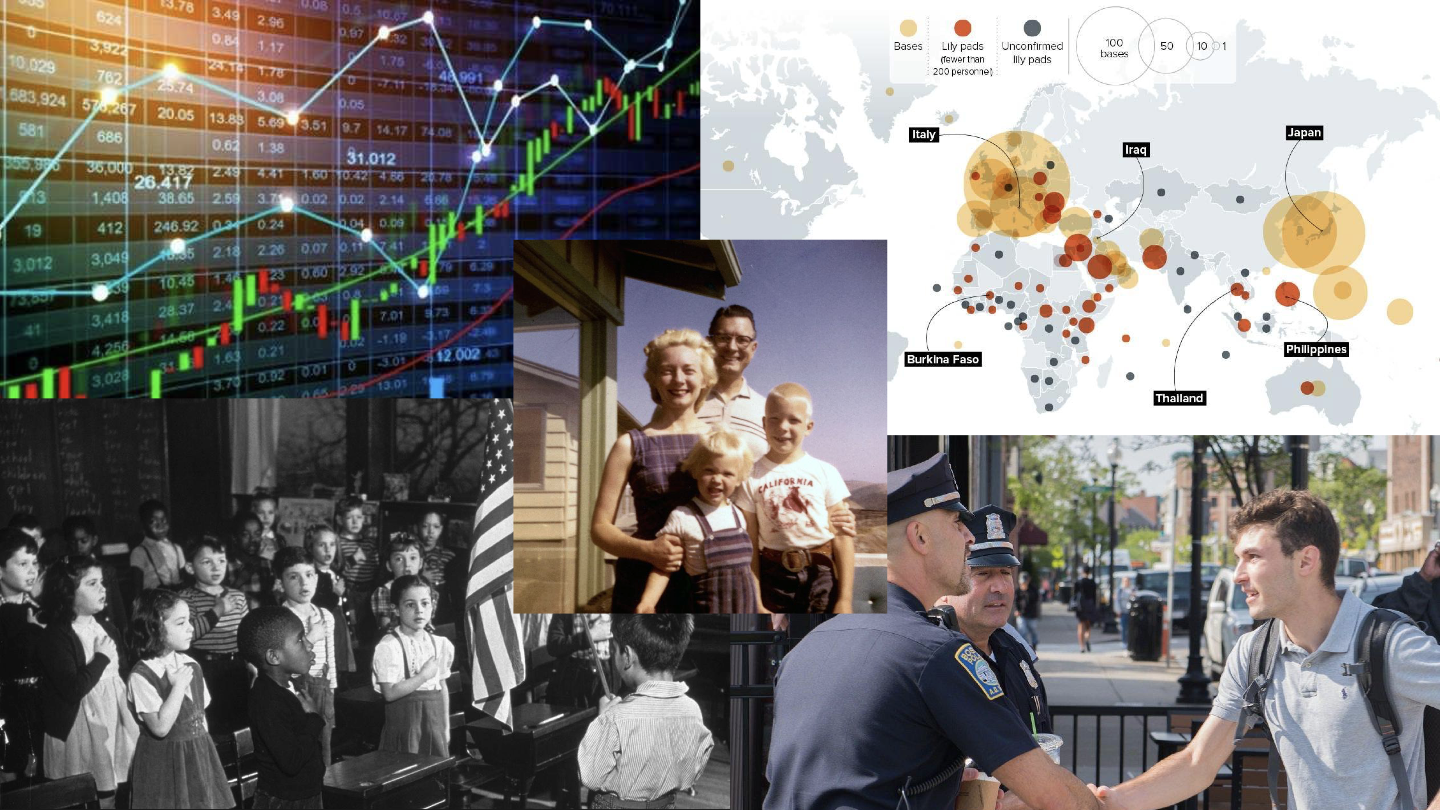

It’s vital to remember that crime is defined not by the people, but by that dominant group–as represented by legislators. Legislators represent not the interests of the people at large–but the interests of that dominant power group, which we call “the State.” So what are those interests, and how does the law protect them?

For example, a country that’s focused on capitalist growth and imperialist conquest needs citizens who obey authority, who express and act on patriotic and nationalistic loyalty, and who produce workers. In a society that’s founded on ideals of white supremacy like our own, those workers should either be white or readily exploitable.

If we identify those as the needs of our example State, we can then examine the laws of the State and see how they work to protect State interests rather than the interests of individual citizens. It then starts to make sense that citizens acting in their own interests, when those interests oppose the values of the State, can be rebranded as “criminals” and subjected to punitive violence.

When we understand laws to serve the interests of the state, rather than the interests of individual people, the popular framing of “criminal” as “evil” makes a lot of sense. It serves the interests of the state for you, personally, to consider someone who breaks the law to be a different category of creature, who deserves to be treated differently than you, who deserves whatever violence they experience at the hands of the state they have undermined with their actions.

That violence–violence we would never accept in any other circumstance – is thus categorized as simply “a consequence” of “breaking the law.”

If we’re going to work under that assumption, though, we need to be able to count on the idea that we know what the law is. That you and I will never be transformed into that creature called “criminal,” and thus become something deserving of state-inflicted violence.

Unfortunately, this strategy doesn’t work–because the law is not concrete. It changes constantly.

Until the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, there was no such thing as an “illegal immigrant” in the United States. Although the status of “citizen” was limited, the ability to enter the United States was open to everyone–and was, in many cases, forced upon the unwilling. Before 1882, you could legally enter the United States with the intention of living here–no passport or visa required. After the passage of the Act, someone completing a perfectly legal journey they might have started years earlier–might find themselves ending that journey as a “criminal.”

In 1919, there was nothing criminal in the United States about consuming, transporting, or selling alcohol. And then, suddenly, in 1920, the same actions that would render a person a respectable business owner–became crimes.

Meanwhile, it wasn’t until the Supreme Court decision in the case of Lawrence v Texas in 2003 that homosexual intercourse was decriminalized. Prior to that decision, any gay couple that shared a bed would be handed the label “criminal.”

The problem here is that your criminal status can change overnight without your behavior changing. The law changes, and suddenly, you can find yourself in a new category–the category of “criminal”–and being in that category strips you of the right to expect a life free from State-inflicted violence. This is especially true if the State’s goals and interests shift in a way that makes it convenient for you to inhabit the category of “criminal.”

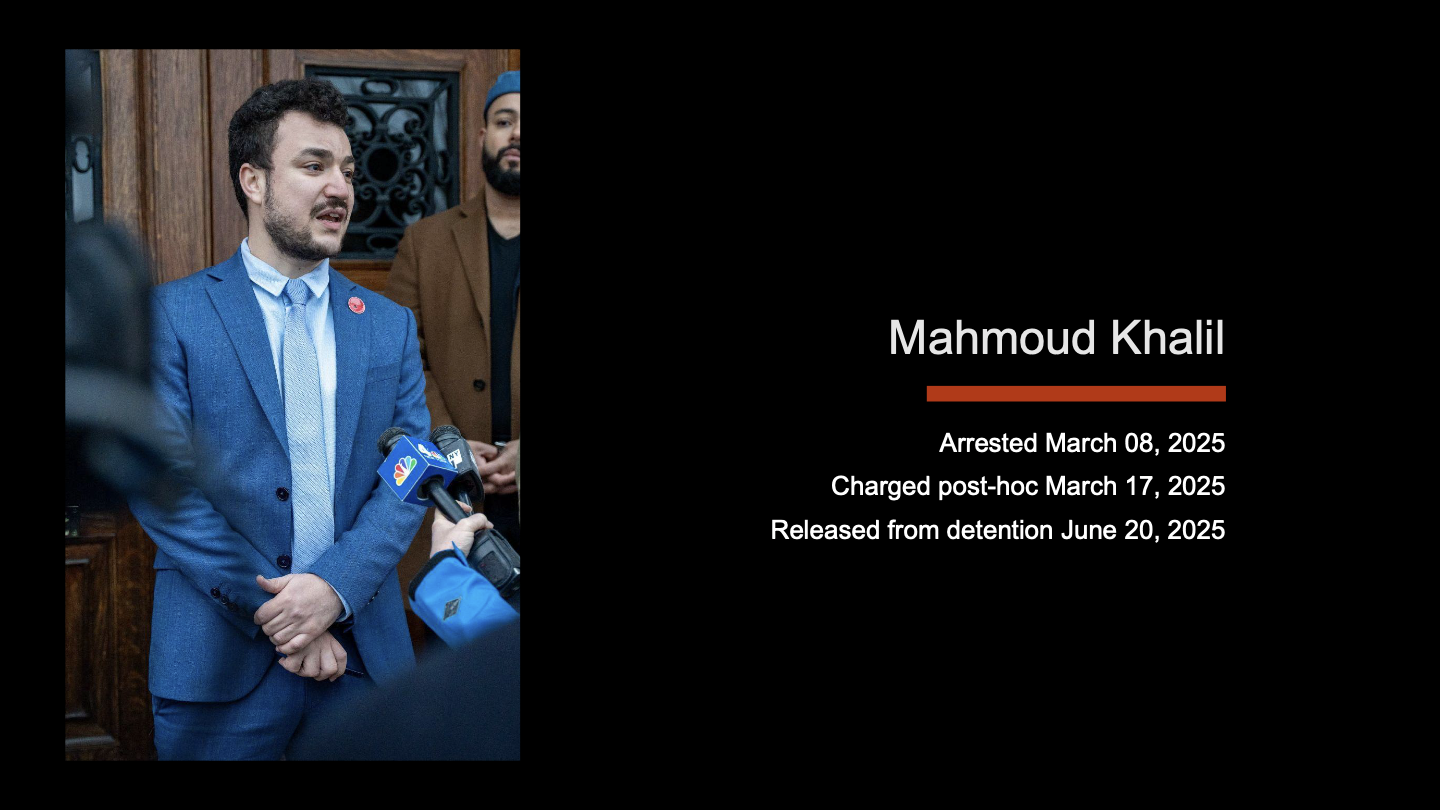

If that convenience is enough of a priority, you may be removed from society first and have a crime assigned to you after the fact as we’ve recently seen in the case of Mahmoud Khalil, an activist who was arrested and detained for nine days before being handed a post-hoc charge–that means a charge of criminal activity after detainment–of falsifying information on a green card application. It required a 104-day legal battle just to get him released from detention. In spite of having committed no crimes, it was convenient to the interests of the State for him to be treated the way we treat people we decide are “criminals.”

It is of course impossible to know how Mahmoud would have been treated if he'd been a Kyle instead of a Khalil, but the rhetoric inflicted upon him by the State and its allies took full advantage of every possible weaponization of his identity—including but not limited to referring to him as a terrorist, in spite of no evidence of any activity on his part that could possibly be interpreted as such. This is just one example of the way the State is prepared to use identity as a cudgel.

The goal of this post-hoc charge was to revoke Khalil’s legal status in the United States in order to deport him. Criminality and citizenship are both forms of legal status, and they’re equally mutable. The State assigns a legal status to you, and the State can remove it, based solely on the goals of the current regime.

I walked into this room today with a legal status of citizen and non-criminal. But Project 2025, the blueprint for the legislative goals of the current political administration in the United States, outlines a clear plan to change that. First by re-categorizing queer and trans narratives as pornography, and then by making the production of anything in the category of “pornography” illegal.

For all I know, by the time I walk out of this room, the legal landscape of this country may have changed in a way that redefines who I am in the eyes of the law, and thus, in the eyes of the State.

I am, at any given moment, Schrodinger's criminal. So are you. So are all of us.

So, what do we do with this? How do we move forward? How do we create a different world, together? How do we embody the spirit of William Gaines and fight this effort to control what we read and what we watch and how we think and who we consider human?

First, we make a practice of compassion for the criminal. Yes, all criminals. Criminals are people you, personally, need to care about and fight for. Not just because it is good and right to extend universal compassion to all living creatures–not just because exercising the muscle of compassion is part of pursuing a rich and loving life.

Maybe those reasons are enough for you–but even if they’re not, this is still in your direct personal interest.

Because your criminal status is not within your control. Your behavior can never be correct enough to prevent you from being assigned the status of criminal. For all you know, this is anyone’s future.

Your kids' favorite teacher, who tells them it’s okay to be different.

The local librarian who recommends your favorite new books to you.

Your queer best friend.

Your mother, your father, your sibling, your spouse.

Your child.

For all you know, this is you.

As of today, you may consider the prior actions of any given criminal to be totally unfathomable–despicable, disgusting, outside of any action you personally could imagine yourself taking. Frankly, that’s fine. There’s nothing wrong with holding deep personal principles and maintaining a practice of morally-consistent actions rooted in those principles.

You may consider yourself separate from the criminal. After all, you pay your taxes, and you don’t drive very far above the speed limit, and you use the crosswalk when you cross the street. You mind your own business and you come to events at your local library. Maybe you think the question of criminality simply doesn’t concern you, because it’s not part of your life.

Or you may consider yourself separate from some-but-not-all criminals. You may already have compassion for some criminals. Maybe there are even some criminals you admire, because their actions align with your principles.

No matter how connected to or distant from “criminal” you currently consider yourself, we are dealing with a growing authoritarian regime that is deeply invested in an increase in media and literary censorship. That means that being in this room and reading this book could make you, in the eyes of the State, indistinguishable from a person who did real material harm to another human being.

It could make you a criminal.

Regardless of where you stand on this–regardless of how you see yourself in relation to the criminal–you must always remember that, in the eyes of the State, the criminal that disgusts you and the criminal you admire and the criminal you might become are indistinct. You have no power over what punishment you receive once you are assigned the identity “criminal.” You all suffer at the same discretion of the same state for breaking the law, whether you knew you were breaking it at the time or not. Whether it was established as a law at the time or not. Whether it makes sense or not.

It doesn’t matter.

When you agree that the State should be allowed to inflict violence on the criminal from whom you think you are different, you are agreeing that the State should be allowed to inflict violence on your neighbors and your loved ones and yourself and your children.

So that is the first thing we must change. We must stop agreeing to that violence. We must speak up for the criminal when we hear others agreeing to that violence. We must pursue justice and protection on behalf of the criminal.

That was the first thing for us to work on. Now here is the second: We must fight media and literary censorship at all costs and on all fronts. Media and literary censorship allows the dominant group to steer your perceptions of what is or isn’t acceptable; of who is or isn’t a villain; of how people should or should not treat each other.

These two fights are deeply connected. If you have unlimited access to unlimited narratives and perspectives, you’re at risk of critical thinking. You might start developing your own perspectives on these issues, feeling compassion for people who are labeled "criminal" because they don’t serve the interests of the State–even reconsidering whether or not you agree with the interests of the state to begin with.

This directly opposes the goals of media and literary censorship. The Comics Code explicitly forbade content that might “injure the sensibilities of the reader”–meaning content that would force the reader to engage actively with those sensibilities.

If the stories you read exist only to instruct you about what is good and bad, right and wrong, acceptable and unacceptable–then you are left in the passive posture of the student, rather than getting the opportunity to explore the boundaries of your own perspective.

If your access is limited to narratives that reinforce what you have already been told is important and correct, then you never have to ask questions about what you do and don’t agree with.

If your sensibilities are never injured, then you will have no cause to decide for yourself whether you think those sensibilities are worth protecting, and at what expense.

While we do that work, it is also necessary to oppose media and literary censorship–because, frankly, we’re a long way from getting the State on board with the idea that violence against its own people in the name of “criminal justice” is not the answer.

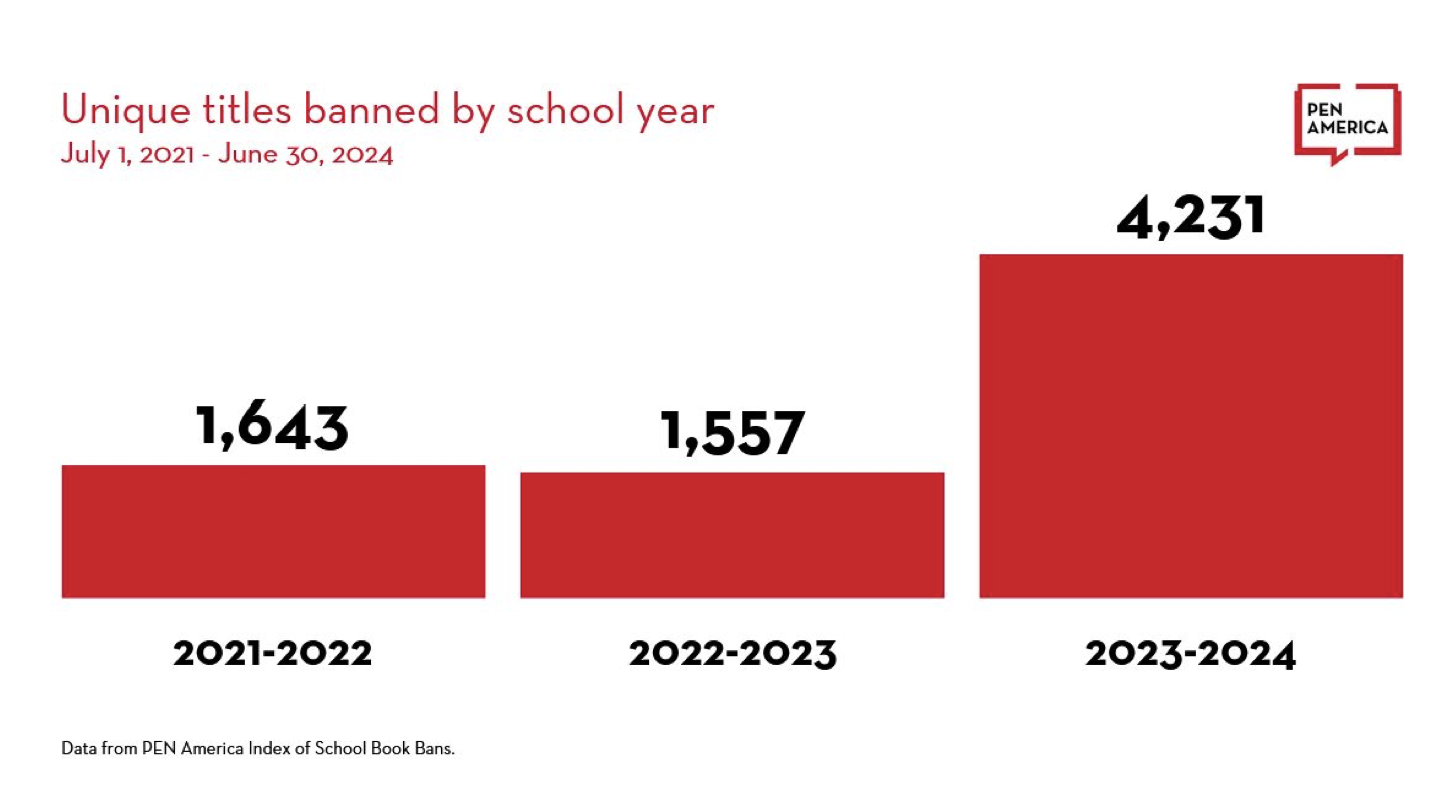

Exposure to a wide range of ideas and narratives will equip more people to engage in the fight against state-inflicted violence and the dehumanization of criminals. So right now, we have to specifically work against media censorship – especially book banning, which is the current forefront of media censorship efforts. We have to work to prevent readers, writers, librarians, filmmakers, artists, dancers, singers, and creatives across all fields from being assigned the label of ‘criminal’ in order to make our stories disappear.

There are a few actions you can take now to help fight literary censorship and exercise your compassion for the criminal.

First, if you’re an author or publishing professional of any kind, you can sign up for Authors Against Book Bans or Publishing Professionals Against Book Bans, two organizations that are fighting book banning and censorship legislation across the US.

You can attend your local school board meetings and local city council meetings, and speak up when you learn of efforts to ban and censor books in your local schools and libraries. Find out where to start at civicsearch.org.

You can attend de-escalation training, so you know what to do in situations where violence is being used to enforce censorship or to victimize someone who has been assigned the status of criminal.

You can sign up for local ICE Rapid Response teams, so you can help support people who are currently being unpredictably assigned the status of “criminal” to justify the violence being inflicted upon them.

You can learn the identities of your representatives and contact them to make it clear that you, a voter in their constituency, do not support censorship, book banning, criminalization of creativity, or victimization of criminals.

You can get involved with organizations like the Equal Justice Initiative, which is committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, to challenging racial and economic injustice, and to protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society.

And you can get involved with organizations like Books to Prisoners, a project with the mission of getting books into the hands of incarcerated people, because even as we strip them of their rights and treat them as less than human, the American prison system tightly controls what books “criminals” are and aren’t allowed to read. For example, How to be an Antiracist is often banned, while Mein Kampf is not.

Those few steps are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to work that’s already being done to make our world a better place. Work that’s been happening for generations. People are fighting for your rights, as a reader and as a human being. You can be part of that fight. There’s so much we can do–and we get to do it together.

Thank you so much for being here with me tonight. I hope we leave here tonight and find ourselves in a world where we can read, speak, think, love, and live freely. And if we don’t–if we find ourselves in a world like the one in Upright Women Wanted, where stories are tools of oppression rather than liberation–then I’ll look forward to being a criminal alongside you.

Member discussion