Traveling with a Chronic Illness

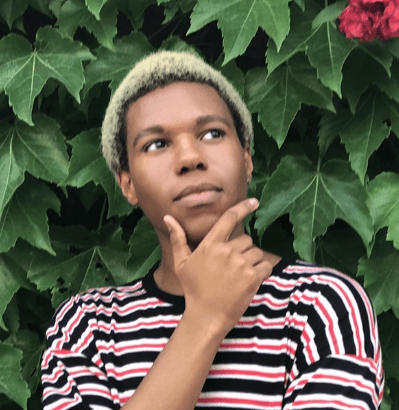

S.B. Divya (she/any) is a lover of science, math, fiction, and the Oxford comma. She is the Hugo and Nebula nominated author of Meru and Machinehood. Her stories have appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies, and she a former editor of Escape Pod, the weekly science fiction podcast. Divya holds degrees in Computational Neuroscience and Signal Processing. Find her on Twitter as @divyastweets or at www.sbdivya.com.

There is a moment of infinite possibility when an airplane leaves the ground, when the world drops away and you hang suspended, impossibly defiant of gravity’s firm grasp. The first time I flew overseas, I was five years old, and my parents were moving from India to the USA. I felt no fear, only excitement, and I continue to prefer the window seat to this day. The realities of travel, however, have changed for me. All voyages require some planning and the further from home you go, the more you have to think in advance, but when you have a chronic illness or a disability, that one thing you forgot becomes a far greater burden.

I learned all this first hand after I contracted ME (myalgic encephalomyelitis, AKA chronic fatigue syndrome) as a complication of Long Covid. This condition means that my body has strict energy limits, and if I exceed those too much, I experience muscle aches, chest pain, and exhaustion for the following week or two. This is known as PEM, or post-exertional malaise, which might evoke the image of a Victorian aristocrat with her hand dramatically backed to her forehead. The condition is, unfortunately, a lot more serious, and the best way to avoid it is to “Stop. Rest. Pace,” a common motto for people with ME. Needless to say, this puts a damper on being spontaneous with activities, especially while traveling.

Before I had this illness, I was generally in good health. I had pretty bad myopia, but I corrected it with contacts and later on with surgically implanted lenses. A couple years prior to Covid, I developed chronic migraines that were triggered by air-conditioning and cold, dry weather, but I could manage them by taking painkillers or wrapping my face in a scarf. Neither of those prevented me from traveling on long-haul flights, going on hikes, SCUBA diving, exploring a new city, or experiencing other types of adventures.

With Long Covid and ME, however, there is nothing to reduce symptoms or alleviate the effects of PEM, other than lots of bed rest. To improve circulation, I spend most of my day with my legs up. This means that I can’t be upright in an airplane seat or in a car for more than a couple hours. Road trips now require me to sit sideways in the backseat of a car while someone else drives. Long distance flights mean paying for extra seats so I can spread out, or spending even more money for a fully reclining seat in business class (if it’s available). I have to arrange for wheelchair assistance at airports, use door-to-door taxis for rides, and rent rooms at small inns or private homes rather than big hotels that require a lot of walking. All of these require advance planning, both for the travel arrangements and for the additional costs.

Once at my destination, I have to consider factors like restaurant locations, whether I’ll have easy access to delivery services, and whether I can make simple meals for myself rather than going out. Sightseeing might necessitate renting a wheelchair (powered if I’m alone) and making sure there are accessible routes, or marking places to sit and put my feet up. Wilderness destinations mean finding a spot with a nice view where I can comfortably spread out (and keep myself entertained) while my travel companions do something more active. Visiting with friends and family requires careful scheduling so that I give myself a day to recover between each outing. These kinds of logistical gymnastics are probably familiar to anyone who deals with chronic illness or disability.

One of the main characters in my novel Meru has sickle cell disease. At the start of the story, she has spent all her time at home (on Earth) under the watchful care of her parents, but before long, she’s off to the titular planet. She can’t just casually take a trip through space, though. Because she has a medical condition, she needs someone along who can take care of her in case of a health crisis. She needs special medication and equipment. She needs to do a lot of advance planning.

We will inevitably miss something because we’re only human. On my solo journey from Los Angeles to Chicago, I had a carry-on suitcase. Having arrived at the end of the jetway by wheelchair, I assumed that a flight attendant would help me stow my luggage. They refused and said they legally could not. Lucky for me, another passenger was willing to help. Another time, however, I was at a terminal without a wheelchair and no one would look after my luggage, so I had to overexert myself by carrying it around while I got some food. Life doesn’t always go according to plan – in reality or in fiction – and having a disability brings an added layer of stress to plot twists.

I’ve heard people describe this as an extra tax for being disabled. Not only do we have to suffer the various effects of our conditions, but we usually have to spend extra money for equipment, accommodations, and assistance. In my case, it means that a trip someone else can do in two days could take me an entire week. For my character, she has to be mindful of her hydration levels, exercise, and breathing. Someone else might need medication to help with anxiety of navigating a crowded airport. Whether it’s extra time, money, or help, it’s something else that we have to account for.

After a while, these kinds of thought processes become second nature. The good part is that if we have the right resources – especially money and help – we can go out and see much of the world. We might have to go about it a little differently and with a lot more forethought than healthy, able-bodied people, but we can have the kind of adventures that heroes do in the epics – including those in outer space.

For more reading on this topic:

- https://www.teamhazardridesagain.com/

- https://curbfreewithcorylee.com/

- http://www.cfsselfhelp.org/library/ten-tips-travel

For five centuries, human life has been restricted to Earth, while posthuman descendants called alloys freely explore the galaxy. But when the Earthlike planet of Meru is discovered, two unlikely companions venture forth to test the habitability of this unoccupied new world and the future of human-alloy relations.

For Jayanthi, the adopted human child of alloy parents, it’s an opportunity to rectify the ancient reputation of her species as avaricious and destructive, and to give humanity a new place in the universe. For Vaha, Jayanthi’s alloy pilot, it’s a daunting yet irresistible adventure to find success as an individual.

As the journey challenges their resolve in unexpected ways, the two form a bond that only deepens with their time alone on Meru. But how can Jayanthi succeed at freeing humanity from its past when she and Vaha have been set up to fail?

Against all odds, hope is human, too.

Add Meru to your tbr here. Order it from your local independent bookseller, or order it via Bookshop.org to support independent booksellers throughout the US and the UK. For international shipping, you can try Barnes & Noble. You can also request Meru from your local library — here’s how to get in touch with them. And if you need to order from the Bad River Website, here’s a link that will leverage your order for good.

In the meantime, care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

—Gailey

![Guest Host [sarah] Cavar](/content/images/size/w750/2025/03/COVER---Failure-to-Comply.jpg)

Member discussion