You* Are Free to Move About the Country (City)

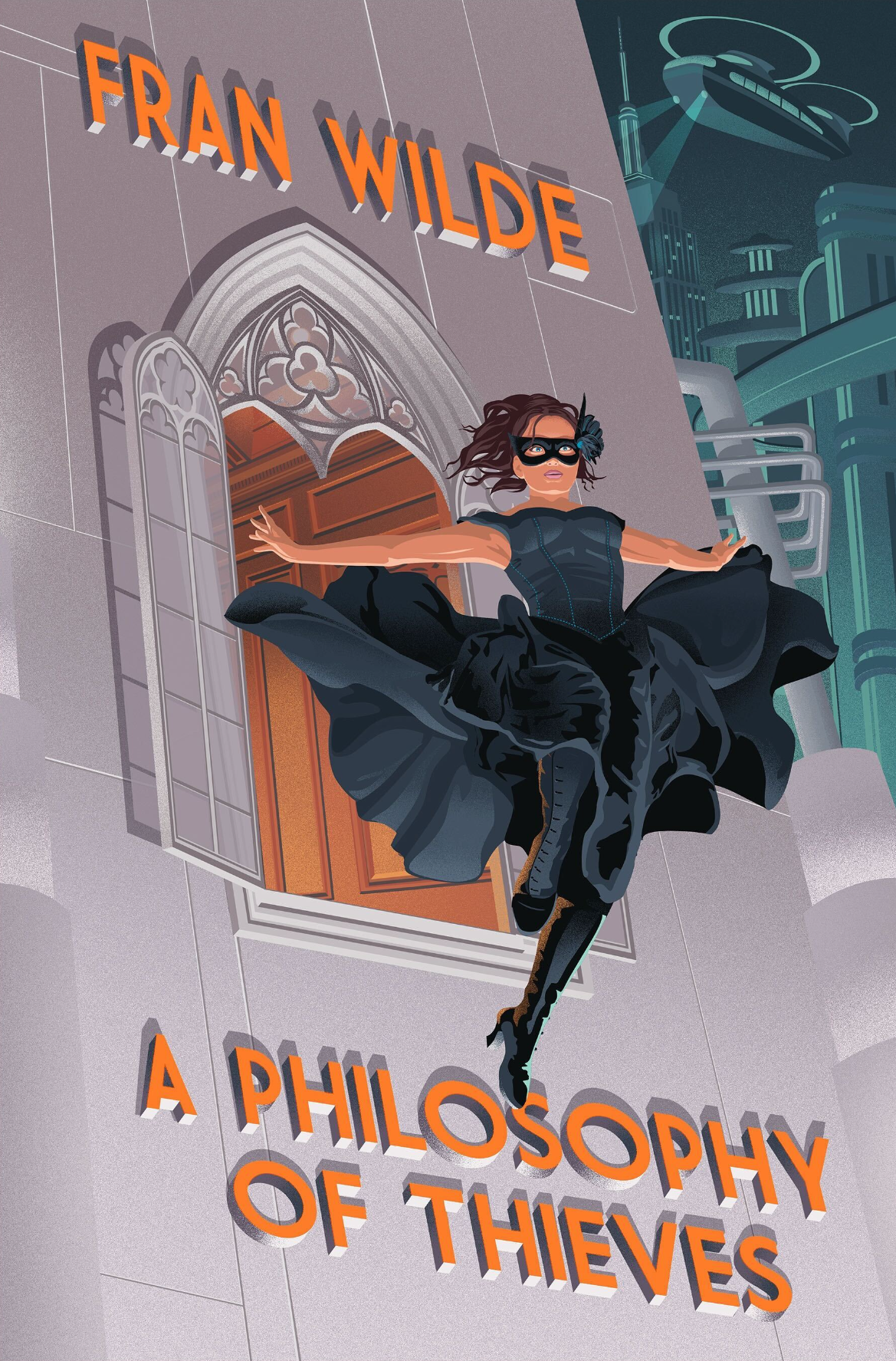

Two-time Nebula Award-winner Fran Wilde has (so far) published nine novels, a poetry collection, and over 70 short stories for adults, teens, and kids. Her stories have been finalists for six Nebula Awards, a World Fantasy Award, four Hugo Awards, four Locus Awards, and a Lodestar. They include her Nebula- and Compton Crook-winning debut novel Updraft, and her Nebula-winning, Best of NPR 2019, debut Middle Grade novel Riverland. Her short stories appear in Asimov’s Science Fiction, Tor.com, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Shimmer, Nature, Uncanny Magazine, and multiple years' best anthologies.

The Managing Editor for The Sunday Morning Transport, Fran teaches or has taught for schools including Vermont College of Fine Arts’ MFA and St. Mary’s College of Maryland. She writes nonfiction for publications including The Washington Post, The New York Times, NPR, and Tor.com. You can find her on Instagram, Bluesky, and at franwilde.net.

Travel is something I love. It’s part of my psyche. When in doubt or trouble: move. When brain feels stagnant: move.

The thought of not being able to set out freely, by car, or train, plane, foot, kayak, bus, or bicycle, gives me a sense of deep unease. So when I began writing my new novel, A Philosophy of Thieves, nearly a decade ago, I decided to play out the possible impacts of a catastrophic event like the Mess on freedom of movement, from the points of view of characters with varying ability to move freely.

In many parts of the world (but not all), the right to travel freely, and to settle where one likes within one’s own country without undue restriction is currently seen as a basic human right.

I’ve been lucky to travel quite a lot—to conventions, to teach abroad, to visit family. I’ve benefitted in many cases from robust public transportation systems, from the DC Metro (truly lovely, ps: free the district), to London’s underground (amazingly complex and logical once you get used to it), to Japan’s national railway system (I have never had a train sing to me, but these do). On each journey, while I’ve waited in lines, crammed my skincare routine into packages the size of D batteries, and worried about the privacy of my communications devices, I’ve arrived at my destination and been able to go about my business. (I am also white, which means my passage through various checkpoints is not impacted by racism; and I use a cane for mobility, which does impact my travel experiences.)

By traveling, I’m able to connect with other writers new and familiar, as well as with others in the publishing business. Those connections teach me new things, and let me be more discoverable to others. Travel, for me, means discovery and opportunity, albeit often at great expense.

But today, that’s already not true for everyone. Especially in my home country, to our collective shame, travelers are now routinely pulled aside and worse over appearance, nationality, politics, and more. It is dangerous and terrifying for trans, gender non-conforming, nonwhite, and politically active people to attempt to enter and leave the country. Depending on location, pregnant people traveling have become suspect; and the expense, health risks, (to name a few) and time required for travel (especially when taking time off from work) are becoming restrictive to many others. Traveling while disabled—especially those using wheelchairs and more complex devices—is its own small circle of hell filled with stairs and broken elevators. Yet people still travel because they need to: moving between cities, states, and countries for work and to connect with others, or leaving situations that impact their livelihoods, their families, their safety. But those gateways are now much narrower, with some basic rights even shutting down.

In A Philosophy of Thieves, I imagined a time when travel for many (*but not all) is vastly more restricted, even within the city where my characters live. This is not a big plot element, but it is a major setting detail in this post-Recovery story (aka a post-post- Apocalypse story) set after what those who have money call “the Turbulence,” and those who don’t call “the Mess.”

The Mess is a combination of effects on the world that have rendered many areas of the world standalone city-states. The makeup and stability of these cities varies, but the primary city in the novel, New Washington, is fairly stable. Things are getting much better (all the advertisements agree!). There’s entertainment (especially in the form of rich-people-watching via the local gossip feeds, and wealthy parties where the rich may hire thieves to try to rob the host and guests… but that’s a different essay), dining, business opportunities, and security.

Beyond the walls of New Washington lies the Skirts, where those who do not have citizenship must keep moving around the city in a slow caravan (yes this is a DC beltway joke, IYKYK) to avoid being arrested and sent away for malingering. That is a different kind of putative, resource-draining movement. Those in the Skirts cannot legally enter the city (the word ‘legally’ is doing a lot of heavy lifting there) where access to city services, including education feeds, healthcare, data, and job networks, is a benefit of citizenship, and is pay-to-play.

And those who do live in New Washington can’t—except if they’re working—travel to the much nicer area where the wealthy live without an invitation.

Meantime, the wealthy have access to many more options and can move between these spaces and beyond in their own vehicles for work or entertainment purposes. This means that the freedom of movement even within New Washington is stratified and class-driven.

Beyond New Washington’s borders, travel is, unless one is very wealthy or being sent away by the somewhat quixotic carceral system, practically nonexistent. It is too dangerous, far too expensive, and many of the transit lines we are familiar with (or wish could be improved to international standards—AmtrakI am looking at you), are still disrupted.

What does it mean when access to work opportunities and discovery is limited to a single city, and few specific points within that city? When starting out fresh in a new place is nearly impossible? When services—from civic to education—are tied to status as a citizen of a particular spot? When social connections—and reputation—are just as constrained?

One character in A Philosophy of Thieves who took a chance on leaving the city of their birth to come to New Washington to change their fortunes, is doing their best to hide the circumstances of it. Another is trying to elevate their family by earning their way out of the Skirts in secret. And several others don’t even think about the intricacies or cost of travel, as they hop on their private transport on a whim. Sound familiar?

Restricted movement means, for many—both in A Philosophy of Thieves, and beyond—a narrowing of opportunities, less ability to change material and social status, much more risk of falling prey to rising costs and complex employer ethics. The truth of the matter, as with much of science fiction, is that these issues are at play and impacting people’s lives now, even as some of us (a narrowing number) continue to be able to move between places freely. The ability to travel is much more than networking or seeing new places. It is, and must remain (and expand as), a basic human right. And that’s fact, not fiction.

A Philosophy of Thieves by Fran Wilde

The Canarviers are the premier performance thieves in New Washington, blending astonishing acrobatics, clever misdirection, and daring escapes to entertain their rich patrons. As King Canarvier has always told his children, their work is art. Who else could titillate audiences with illicit history lessons and tease them through the gaps in their much-prized security?

Now that they’re adults, King’s children feel their divisions more than their bonds. Roosa attends an exclusive finishing university, blending in so well she’s unsure where she belongs. Her brother Dax craves a chance to prove himself, stifling under his father’s caution.

Then King disappears.

With only days to buy mercy before their father is lost forever, Roo and Dax must compete in a high-stakes Grand Heist, pushing down their resentments to work together. Against a technocrat wagering more than he can lose, a security chief with a taste for pain, and a society beauty with secrets of her own, any misstep promises catastrophic ruin.

But Canarviers are artists. And they perform best when the pressure is on . . .

Member discussion