Your Tongue Remembers | Duò Làjiāo with Duò Jiāo Yú

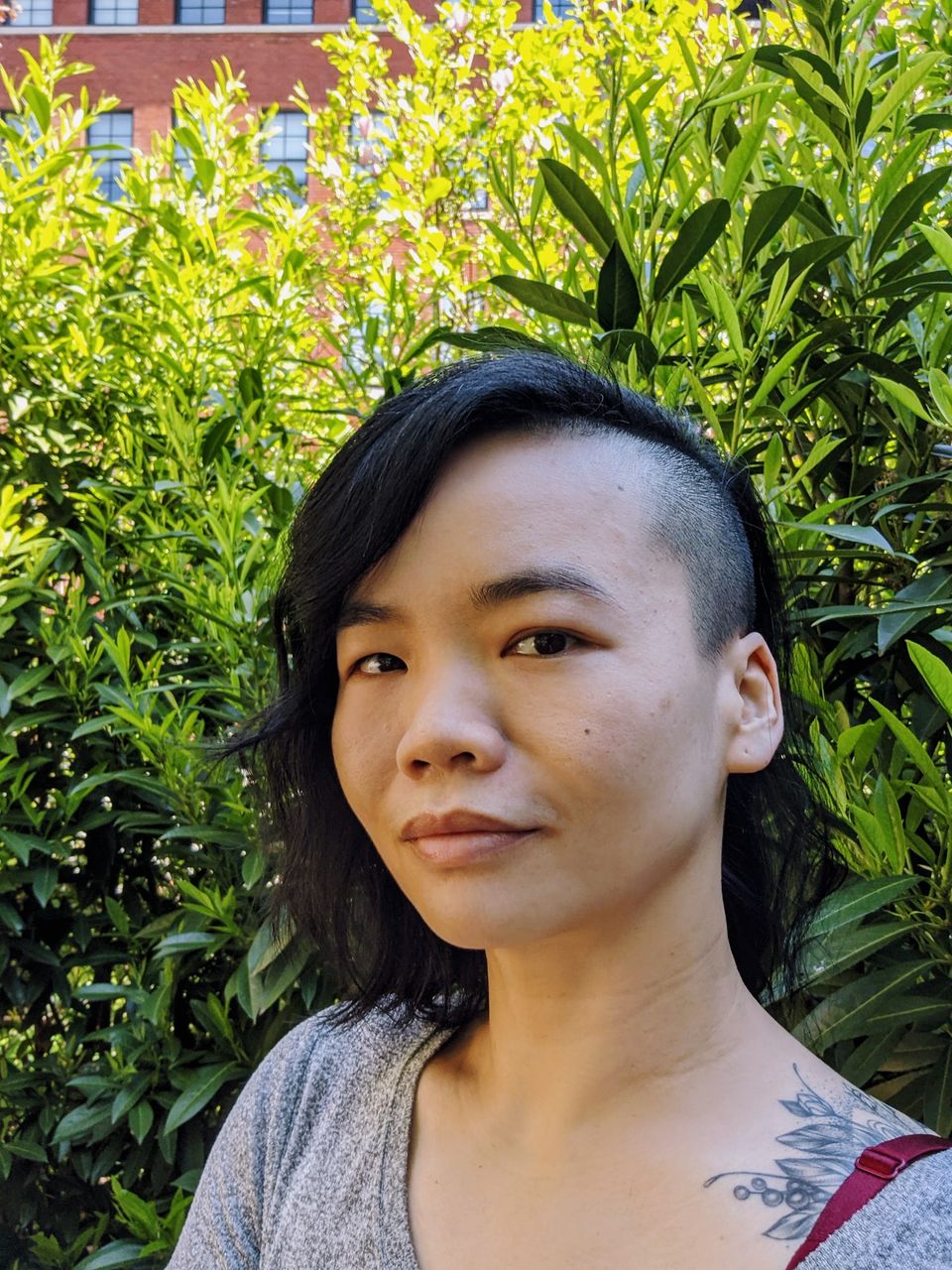

J.M. Coster (Jen) is a Chinese-American erstwhile MD turned professional storyteller. She writes speculative fiction and is an associate editor for the Hugo-nominated science fiction podcast magazine Escape Pod. She has worked as a process consultant for multiple award-winning speculative fiction authors. In her role as narrative designer at the critically acclaimed video game studio Butterscotch Shenanigans, she tells the most honest lies she can.

My grandmother never told me she loved me. Well, more precisely, I never heard her say those words. Not to me, not to my brother, not to my mom, her daughter.

My family is from the Hunan region of China, a region known for spicy food and Mao Zedong. We are not particularly effusive, better at tempers than we are at tenderness. It’s easier to express anger or criticism than it is to offer up your heart, soft and dear and so easily bruised.

This is something I struggled with as a sensitive child. For me, words are a gift. They are a truth. A window into someone’s inner world. So when I was little, seeing the casualness with which my friends’ parents verbalized their affections, I wondered what the lack of words said about my family.

I was too young then to think about the dynamics of cultural assimilation. Of how hard it must have been for my parents to leave behind everything they knew to build a life somewhere completely foreign. Of what it must have felt like to start with nearly nothing, without even words to rely on.

꘏

I’ve spent a lot of my life feeling a profound disconnection from my cultural heritage, a feeling common to many third culture kids. It’s the cost of my assimilation.

During my childhood, my parents were learning English while I was forgetting the little bit of Chinese that I knew. We spoke to each other in fits and starts, each of us hurt (in the exact same but also completely different ways) by the lack of understanding. With my grandmother, I barely spoke at all. She didn’t know English, and I was eventually too ashamed of my broken Chinese to try.

And yet, China was my first home, and Chinese was my first language. At some point in my early life, it was all I knew. Even though I don’t remember what it was like to have those musical words fall from my mouth at the speed of thought, there are certain shapes my mouth still knows how to make, certain tones my ears still know how to hear—things my mind and body have held on to as a record of my past.

The words that my tongue remembers, though it’s clumsy in the shaping of them, are mostly related to food.

It always comes back to food.

I don’t know what it’s like to have to make concessions related to cultural identity, for success to require the rejection of things that make up the fabric of you, for victory to feel like surrender. But I do know what it feels like to grieve the loss of something I never really had in the first place.

꘏

Like many other families, my family was devastated by the Cultural Revolution. I don’t know the specifics. No one would talk about them whenever my brother and I would ask, but they carry the wounds all the same. My grandmother knew hunger intimately, and all she wanted for us was abundance.

I don’t remember her telling me she loved me, but I do remember how she used to slip the juiciest morsels of meat or the crispiest pieces of fat into my bowl or into my brother’s. I remember how closely she paid attention to the things we liked to eat and how those things were always present in excess. One summer when we were visiting her in Chángshā, she noticed that my brother and I would polish off our noodles at breakfast but have leftover rice in our bowls at lunch. At every meal thereafter she had noodles ready just in case we wanted that option.

When my grandmother moved to the US and into my mom’s house, she couldn’t go grocery shopping on her own anymore. Instead, the pantry was where she would make her selections. After I left home, whenever I visited, she would come to my room with a small basket of fruit that she had taken from the kitchen and squirreled away in her bedroom, that she had saved for me. The juiciest peaches, perfectly ripe lychee, persimmons with just the right amount of give, always more than I could possibly eat on my own.

When I left for college, she sent me duò làjiāo, bottled in repurposed jars and double wrapped in plastic to protect against leaking. As a teen, I remember feeling passing annoyance at the loss of precious dorm room fridge space, but she knew better than I did what it meant to leave the familiar. And on dark Chicago winter nights when I was a thousand miles away from the things I knew, I would crack open that jar and let the smell take me home.

꘏

There are still a handful of tastes my tongue remembers. Some I meet and meet again with regularity so my tongue never forgets, the memory instead transforming with each fresh iteration. Others I haven’t felt bloom across my taste buds in over a decade, but when we find each other again it will feel exactly as it should. And some tastes I’ll probably never find again, the memory slowly fading with distance and time, the loss as inevitable as silence.

When I close my eyes, I can see the bright searing red of the chopped chilis and the scattered black fermented soybeans. I can smell the floral notes of the peppers, the savory aroma of garlic, the slight sweet tang of fermentation. My nose prickles with the memory of sweat, and my mouth floods with saliva. My tongue remembers.

After my grandmother died, I tried to make the final jar of her duò làjiāo last as long as possible. Since that last spoonful scraped from the bottom of the jar, I have yet to find that same taste again, my tongue never satisfied.

꘏

There’s a proverb that says, 贵州人不怕辣, 四川人辣不怕, 湖南人怕不辣 (Guìzhōu rén bùpà là, sìchuān rén là bùpà, húnán rén pà bù là)—“Guizhou people like heat. Sichuan people don’t fear heat. Hunan people fear the lack of heat.” Duò làjiāo is a condiment, a side dish, a flavor enhancer, a dare. If pressed, I’d say it would be most accurately called a relish. Funny, now that I’m thinking about it, it’s not categorized in Chinese. Duò làjiāo just is.

It’s straightforward to make, the process so plain it’s barely a recipe. So simple that every part has an outsized impact on the final product. At its core, it’s chilis and salt. Maybe garlic, fermented soybeans, a touch of báijiǔ if you want to add a flourish.

When duò làjiāo has had time to sit and marinate, the result is complex, bold, assertive, salty, and hot. Hot enough to make your scalp itch and your body move. Hot enough that the first time my husband had a Hunan banquet meal where most of the dishes incorporated chopped chilis in one form or another, he got an impressive nosebleed and had to endure a solid fifteen minutes of well-meaning but ultimately ineffective advice from my cousins.

It’s not a blossoming heat or a creeping one. There’s no subterfuge involved. It’s hot like a humid summer afternoon next to the Xiangjiang river, sweat trickling from your hairline down the back of your neck, skin peeling molecule by molecule from a plastic chair. It’s a cleansing, implacable kind of hot.

Duò làjiāo is used in a variety of stir-fries, braises, and pickles. A holiday celebration isn’t complete without a whole steamed fish covered with the stuff, the vibrant red chopped chilis and a scattering of green onion obscuring tender, flaky, and surprisingly mild meat. Or you can simply put a few heaping spoonfuls of duò làjiāo in a small dish alongside everything else and let people help themselves.

꘏

When I think about my family, I picture them in the kitchen. It’s the one place I remember them being unapologetically themselves. My mom humming folk songs to herself while washing piles of leafy greens or scrubbing daikon radishes. My grandmother’s gnarled fingers wrapped around the handle of a cleaver as she carved thin slices of spiced braised beef and tendon. The proud close-lipped smiles in response to exclamations of deliciousness and delight, as if to say, “This. This is what food should taste like.”

We’ve always been the most comfortable with each other when we’re eating together. We don’t always speak much, but we don’t need words to understand each other’s experience there. We can see it, on each other’s faces, in each other’s bowls, in which plates are clean at the end of the meal and which ones aren’t.

When I think about my grandmother, I don’t remember much of what she said to me. But I do remember that whenever we were eating together, and I would reach for more duò làjiāo, she would nod and say, 能吃辣 (Néng chī là). You can handle the heat. You are of us. Your tongue remembers.

Jen’s Duò Làjiāo with Duò Jiāo Yú

This recipe for steamed fish with chopped chilis and a spicy Hunanese condiment will make at least four generous servings.

Get the Recipe: PDF, Google Doc

If you’d like to own the Personal Canons Cookbook ebook, which collects all these essays and recipes in easy-to-reference, clickable format—plus loads of bonus recipes from me!—join the Stone Soup Supper Club. The ebook is free for subscribers, who will get the download link in their inboxes in the first Supper Club email of 2024!

If you’re a paying subscriber, come by the Stone Soup Supper Club for early access to this month’s recipes, our weekly chat, and more community! I can’t wait to find out how you’re doing. And if you’re not a paying subscriber, please consider joining the Supper Club or becoming a booster! Paid subscriptions keep the lights on here at Stone Soup, and every subscription makes a difference.

—Gailey

Member discussion