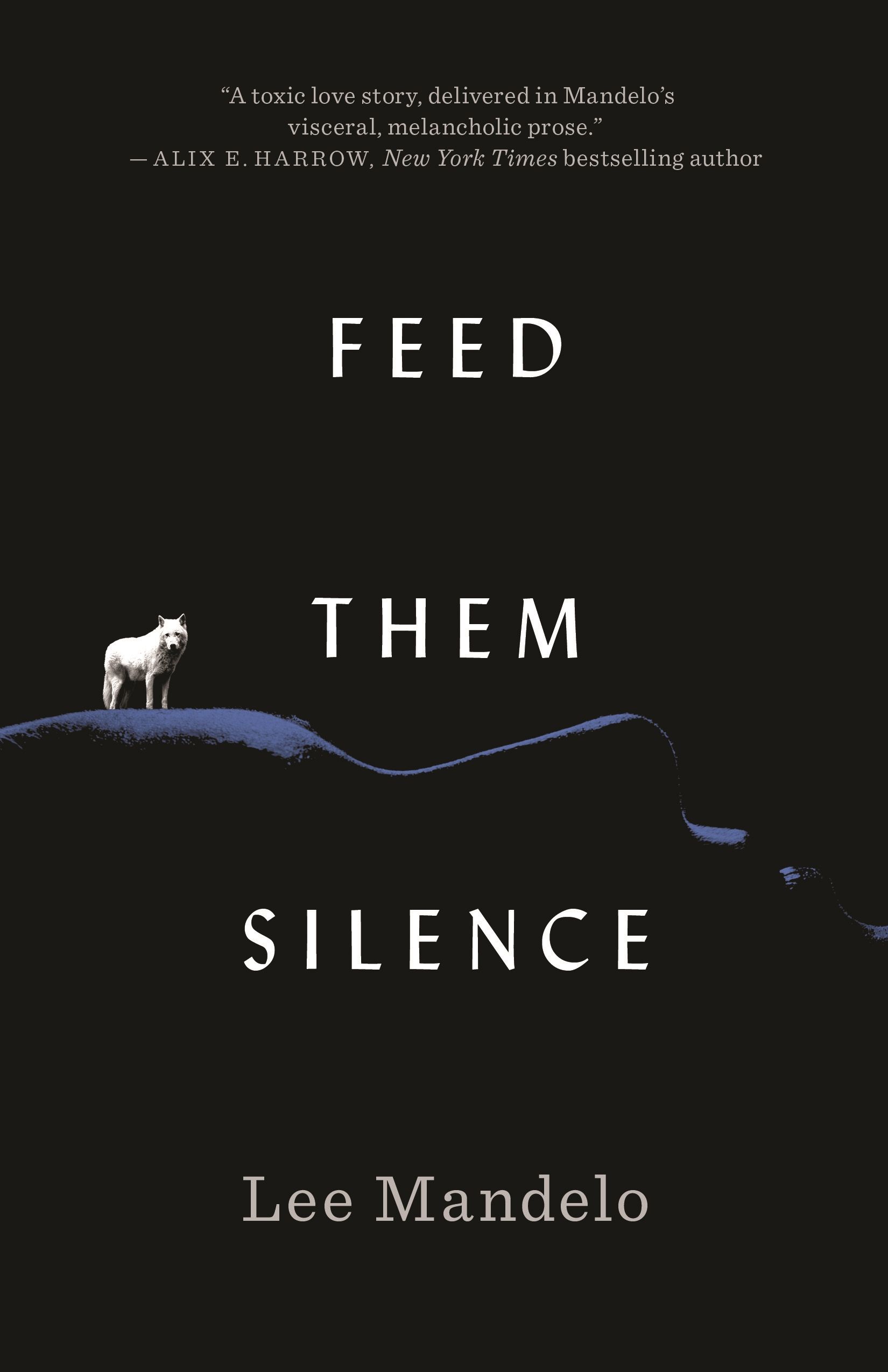

Exclusive Interview with Lee Mandelo: Feed Them Silence

What does it mean to "be-in-kind" with a nonhuman animal? Or in Dr. Sean Kell-Luddon’s case, to be in-kind with one of the last remaining wild wolves? Using a neurological interface to translate her animal subject’s perception through her own mind, Sean intends to chase both her scientific curiosity and her secret, lifelong desire to experience the intimacy and freedom of wolfishness. To see the world through animal eyes; smell the forest, thick with olfactory messages; even taste the blood and viscera of a fresh kill. And, above all, to feel the belonging of the pack.

Sean’s tireless research gives her a chance to fulfill that dream, but pursuing it has a terrible cost. Her obsession with work endangers her fraying relationship with her wife. Her research methods threaten her mind and body. And the attention of her VC funders could destroy her subject, the beautiful wild wolf whose mental world she’s invading.

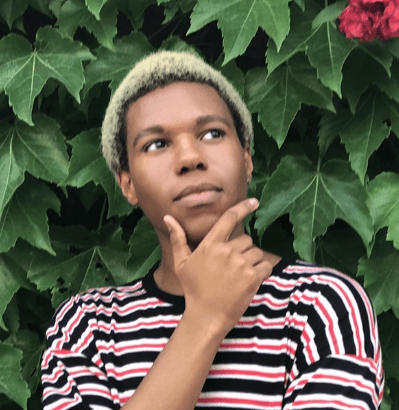

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and occasional editor whose fields of interest include speculative and queer fiction, especially when the two coincide. They have been a past nominee for various awards including the Nebula, Lambda, and Hugo; their work can be found in magazines such as Tor.com, Uncanny Magazine, Clarkesworld, and Nightmare. Aside from a brief stint overseas learning to speak Scouse, Lee has spent their life ranging across Kentucky, currently living in Lexington and pursuing a PhD at the University of Kentucky.

Feed Them Silence is a deeply complex book which tackles difficult, nuanced subject matter in a short amount of space. Can you give some insight into the way the brief length of a novella informs the narrative you’ve written here?

The length constraint of a novella hits somewhere between the compact directness of short fiction—where you're generally going to be able to hit only one theme, or motif, or action effectively—and the potential for sprawl that comes with a novel. But that's such a technical answer! As for me, I tend to know the shape, or structure, of a piece pretty early when I'm noodling on a new project, because it feels so integral to the "what is the art doing (or trying to do)" question.

In the case of Feed Them Silence, specifically, the novella form gives me enough room to weave the science fictional narrative about the neurological interface, the wolves, and the ethics of Sean's work together with the thematic story of her failing marriage: two arcs, one resolution. And one doesn't hold up without the other.

On a second level, though, I was also thinking a lot about affect—the felt emotions around the piece, for both the characters and the audience. The claustrophobic, restrained misery in Feed Them Silence would be harder to sustain over a book three times as long. I'm guessing that's why the novella is a beloved form in several genres that are chewing on problems or ideas how sf does: you've got enough space to do something cool, and do it with complexity, but not so much that any prolonged bad vibes become unbearable. Plus, if you're going to have an ending that leaves a bitter taste in the readers' mouth… sometimes people are more receptive in a shorter format!

Feed Them Silence presents the reader with a tempting experience—you can know what it’s like to be a wolf—and then examines the reality of both the temptation and the experience, in all its exhilaration and sorrow. What’s your approach to temptation in your writing?

Desire is one of the central motifs of my work, and temptation seems to be one of its… flavors, or its reflections? Since we're living through a time where the phrase "degenerate art" is getting bandied around again from multiple directions, alongside a whole host of other super alarming cultural trends, I'm more invested than ever in art that aims for emotional honesty—even when it's ugly, or messy, or simply and humanly imperfect. And desire seems to me to be one of those deep-rooted drives people often feel alternately shy and scared and embarrassed about? Not just erotic desire, but desire for intimacy, for success, for safety. It's cringe to admit you badly want something, or someone.

Temptation, then, is maybe something like "the desire you know you should not feel; a desire that will have consequences if acted on." In my last book, Summer Sons, the protagonist Andrew is tempted by queer intimacy with other men. He's not wrong about the social and personal risks of admitting his sexuality—but, also, doing so is the best choice he could possibly make. With Sean in Feed Them Silence, however, the temptation is for a one-directional and dominating intimacy. She's got plenty of opportunities to find connection—with her actual wife, with her colleagues, with her pet dog—but wriggles out of them over and over again, because it would require reciprocity from her. The desire to be, or know, the wolf pack through this technological interface lets her take without giving, and it's a temptation that has… some real negative consequences, and not just for Sean.

It's fresh on my mind because I just finished reading it, but Garth Greenwell's recent essay "A Moral Education: In Praise of Filth" has a line that I've been chewing on. He writes,

"Coming to judgment in this way is anathema to the novelist because the task of art isn’t to judge, but to know, to observe, to carry out research into the human—and passing judgment is a radically impoverished form of knowledge. An important part of the moral work of art is to teach us how much richer and more capacious our engagement with others can be."

Writing about desire, or temptation—the ways relationships between human and nonhuman animals, the natural world, and culture function (or don't!)—is important to me in part because I'm interested in how we really do engage with one another, both for better and for worse.

The specific choice to center wolves, an animal with which humans historically have a complex relationship, is a narrative masterstroke; presenting wolves as they are, rather than as a romanticized fiction of themselves, is both refreshing and merciless. What made you choose a pack-minded apex predator rather than a more solitary animal, or an animal that occupies a different role in the ecosystem?

I don't think it's a coincidence that wherever there are wolves existing alongside humans, throughout history and across the world, the humans end up developing some strong feelings about the wolves.

On the one hand, "pack-minded apex predator" isn't a bad way of describing us, either! It makes sense why there are so many stories about shapeshifters, "people raised by wolves," wolves as guides and companions and threats. I grew up as a '90s kid reading Julie of the Wolves and the like. Being a very queer child in both the gay and the strange senses of the word, the idea of running off into the wilderness to be one with a wolf-pack had a certain draw. But then you do some research, as I did in the process of writing the novella, and find out mostly-miserable facts like: wolves only survive four to five years anymore on average in the wild. The romantic stories we tell about wolves, versus the short and difficult lives they lead in our collapsing ecosystems, felt like an important fracture to dig into.

On the other hand, "why do we focus on this animal and not that animal" was a common topic in the scholarship I was sifting through for this book too! The nonhuman beings we project on, study, and anthropomorphize tend to be the ones we find cute, or cool, or through which we can see ourselves reflected—not necessarily the ones it makes the most sense to be focused on in a given ecosystem. (A critique Riya has for her wife!) The question I wanted to hover in the air around Sean's fascination with wolves as pack-bonded creatures, then, was: why this form of kinship? What is it about relationships and intimacy (and strength, and violence) that she's grasping for, that leads her to wolves and not bears or deer?

Rather than focusing strictly on scientific research and ethics, Feed Them Silence dives into humanity, love, and relationship struggles. How did your extensive research process influence your understanding of human relationships?

I wrote about the research process in a companion essay for Tor.com, “Being in Kind”: Studying Animal Intimacies for Feed Them Silence, and I think the Donna Haraway and Christine Marran books I cite there—plus some good ol' Ursula K. Le Guin!—have a lot to say about relationships. One of the big things, for me, is that relationships and ethics are… necessarily interconnected and messy? At least, if we're being honest about them.

Not to be the Foucault guy, but when thinking about issues of hierarchy, power dynamics, desire, and intimacy in human relationships the main issue for me is always: you cannot step outside of power. The moment someone decides that the right language, or the right belief, or the right moral action sets them outside its effects… they can no longer see their own enmeshment within systems large and small, be those research labs or marriages. So, I'm instead interested in the ways we manage, negotiate, and find ethical ways to engage with power inside and outside our personal relationships.

And that's a core problem in Feed Them Silence. What does it mean to be in kind with someone else, human or nonhuman? Sean totally sucks at it. She wants so badly to have perfect intimacy on the one hand, and a public relationship that she can perform as a role-model successful queer on the other. In neither case, though, is she willing to give anything of herself in return—it's never an equitable exchange.

Relationships make the world go 'round, and it's no different in (good!) science fiction. Another thing I wanted to chew on, a little, was how few stories in the genre space seem to focus on middle-aged queers… or failing queer relationships! The presence of these kinds of stories feels important to me, too, in the way that it enriches the kinds of people and problems we get to explore.

You’ve mentioned before that messiness, conflicted ethics, and failure are fundamental to the project of this book. How does failure improve a story? How might it improve an author?

Failure is one of the classic queer arts, right? I'm just doing my part.

On a more serious note, though, as an artist it's immensely important to be willing to strive, and risk, and fail—especially if you're trying something new. The editorial voice in the back of the brain, whether it's an imagined disingenuous Goodreads-review-slash-angry-tweet or just the fear that you aren't skilled enough to get right the thing you care so much about… that's deadly stuff. The fear of failure makes you hedge your bets, soften your prose, lean away from the more incisive and insightful ending. It makes you hide from the depths of feeling you'd otherwise be baring to the world in your art. Plus, an unsuccessful first draft can grow into a dope final draft—but if you're too scared to fail, you won't even get the first draft out.

Or worse, it'll be boring and flat, just a caricature.

Then on the level of "what art does for the culture," I think it's wildly important to have stories about fucking up. Badly, even. I'm uneasy with the insistence that our two options as humans are perfect and good or evil and irredeemable. That's way too evangelical for me. Sometimes everyone does shitty things to other people from raw self-interest, at the least. What does it mean, then, to make amends for that? To own your shit and act better? Stories can do that work of modeling, exploring, etc.

In your recent essay at Tor.com, you quote Donna J. Haraway as saying, “[… The] fantasy of full knowledge is a violent fantasy.” In your opinion, where does the pursuit of understanding become a pursuit of invasion or ownership? Is violence and domination intrinsic to this pursuit?

Full disclosure, I could write, like, a thirty-page response to this. I'm going to restrain myself!

The simplest answer is, maybe, understanding requires mutuality and vulnerability? It also requires a willingness to honestly engage with your own standpoint position in the big ol' global web of power, dominance, and consumption. At its most basic levels, I don't think violence is genuinely intrinsic to the desire to know, or study, or understand. Some of the best things humans have to offer one another grow out of our (occasional, imperfect) willingness to listen to one another, share ideas and experiences, etc.!

But, well, I also think of the ways academic research, particularly within the social and hard sciences and double-particularly in the West during modernity, has been an ethical failure in a big way. Colonialism, eugenics, genocides; the gruesome histories of most contemporary medical research in the USA being born of the torture of Black, Indigenous, and other peoples of color; climate catastrophe itself and the oil industry's successful lobbying to continue it through bad science… yeah. I could go on. Violence might not be intrinsic to the desire to know, but it is intrinsic to the desire for nonconsensual ownership, control, and exploitation of others (slash, The Other).

Writing a book like this, especially under the conditions of early pandemic and in isolation, can be incredibly difficult labor. Were there parts of the novella that you loved writing?

On a technical level, I actually had a lot of fun with the prose itself. I was trying to write more crisply, or even coldly, through Sean's perspective—as compared to my usual lean onto a more dense, sensory-focused style. I do get to bust that back out again in Sean's narration of the wolf's experiential world, though.

As for a particular moment in the book, I found the (world's most depressing) sex scene compelling to write because it's a sort of un-weaving of the romantic-erotic arc we'd expect to see in a romance novel. It's purposefully unsatisfying, and that's such a different thing to write than… well, a horny sex scene! I was also playing with some genre expectations around wolf stories and sf, in terms of refusing the expected turns (the wolf does not know Sean in turn after all, for example). All of that kept my brain nice and busy during the isolation phase.

Add Feed Them Silence to your tbr here. Order it from your local independent bookseller, or via Bookshop.org to support independent booksellers throughout the US and the UK. For international shipping, you can try Barnes & Noble. If you prefer audiobooks, here’s a Libro.fm link. You can also request Feed Them Silence from your local library — here’s how to get in touch with them. And if you need to order from the Bad River Website, here’s a link.

In the meantime, care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

—Gailey

![Guest Host [sarah] Cavar](/content/images/size/w750/2025/03/COVER---Failure-to-Comply.jpg)

Member discussion