When It Hurts

I came up with the idea for Love Letters: Reasons to be Alive in a season of profound grief. I have experienced grief before, but never of that magnitude. It was a strange combination of sensations, both acutely painful and paralyzing–like being trapped in a block of gelatine while someone drilled a slow hole through my breastbone.

Every day that I woke up during that season represented a choice to stay in the gelatine, and let the drill do its work. There was a kind dentist’s-office patience to it. Yes, every instinct in me says to flinch away from the needle headed toward my gums, but I will remain still, and I will absorb the pain and the numbness that follows. I will allow time to pass and trust that after the time passes, this will be over.

It was awful, and necessary, and I have never experienced anything more educational in my life.

During this season I stayed with many friends who lovingly opened their homes to me, even though I was (as I warned each and every one of them) a complete shitshow. They were with me when I cried and when I yelled and when I shook with overwhelming, thought-drowning emotion. They took me out on walks and celebrated holidays with me and let me learn the secret nicknames of their pets. They loaned and gifted me clothes and taught me how to navigate icy roads and put clean sheets on their guest beds.

And they fed me.

I can’t eat when I’m upset. It’s something my body decides for me: My throat narrows, my stomach locks, my tongue tastes only static. But the friends who carried me through this season (god, I am so lucky) all found ways to get around my appetiteless state. They remembered, somehow, that I can always eat grapes; they stocked their refrigerators with salami and string cheese, my favorite late-night standing-in-the-kitchen goblin-mode snack; they got gluten-free bread so I could take slow bites of buttered toast. They sat down with me and presented me with cabbage-and-pork-belly soup and fatty chops of unbelievably grassy lamb and little bowls of roasted cashews. They made sure that at least once a day, something nourished me.

And one of them decided to hurt me.

My very beloved friend in St Louis wrote an essay for the Personal Canons Cookbook about a lactofermented pepper relish called Duò làjiāo. I came to stay with them when the grief was very, very fresh. They knew, even before I said it, that I was not likely to be able to eat very much. I believe my precise warning was I am going to be a bad guest. That friend made hot pot (which Kelsea Yu wrote about, separately, for the same essay series) for dinner. This was a kindness in many ways, as it was a meal that allowed me to eat one bite at a time, with no daunting plate piled high or looming threat of waste.

They served the hot pot with a dish of duò làjiāo. It felt like seeing an old friend–this condiment from the essay I edited and published. At the same time, I was immediately daunted. Hunan cuisine does not play games when it comes to heat.

But then I had a thought that would return to me many times in the following months – a thought that led me into many great adventures, and which emboldened me enough to make this essay series into a reality in spite of the towering shyness that makes it very, very hard for me to solicit work from people.

I thought: What, am I scared it’s going to hurt me?

This, you should read in a scathing, incredulous tone. I was, at that time, waking up every day to the worst anguish I’d ever known. It was ceaseless. I felt, most of the time, like I was dying. So why, I asked myself, would I be scared of something so small as pain?

I put some of the duò làjiāo on my spoon and took a bite.

The pain, I discovered, was not small. As my friend says in their essay: “贵州人不怕辣, 四川人辣不怕, 湖南人怕不辣 (Guìzhōu rén bùpà là, sìchuān rén là bùpà, húnán rén pà bù là)—Guizhou people like heat. Sichuan people don’t fear heat. Hunan people fear the lack of heat”.

I can easily assuage that Hunan fear, because at that moment, all the heat that had ever existed was concentrated directly in the center of my tongue. My corneas puckered. I could feel my bones starting to vibrate.

And then I laughed.

Something woke up inside of me with that bite. For the first time since my descent into grief began, I could feel my entire body. My blood was electric. With every breath I drew, I could feel the air rushing over the tender dark whorls of my sinuses and into the raw pink pockets of my lungs. Sweat pearled at my temples and I marveled at the work of my own skin. I was, I realized, alive.

The next night, I ate more. More of the duò làjiāo, and more soup, and more mushrooms and bok choy. I felt something inside of me opening up to the searing, merciless heat of the peppers.

It felt like hunger.

When I left that home to make my way to another friend in another state, I brought it with me. Not the duò làjiāo–I don’t think you’re allowed to take that on airplanes since it definitely classifies as a weapon–but the hunger. Not just for food, but for life. For the world. With it came the feeling that pain is not something to be afraid of, but something to be open to.

Because it means I am alive.

As someone who has had chronic autoimmune and nerve pain for a long time, this sentiment feels almost transgressive. The pain my body produces all on its own–in response to gluten, or rogue antibodies, or the disposition of the moons of Jupiter, who fucking knows–is not meaningful pain. It only occasionally communicates information. Most of the time, that pain is an indicator of nothing at all, and treating it as important or useful serves very little purpose for me.

But my experience in St. Louis opened a door to a different kind of pain. Pain that is information–pain that carries meaning. Pain that is a gift, because a dead thing feels no pain.

That realization came to me over a bottle of habanero hot sauce, across the table from one of the friends who carried me, while I was trying my damndest not to cry about what was lost. I made a pitiable attempt to pass off my tears as a result of the hot sauce (which, in fairness, was a vividly evil condiment)–and I realized that both were the same gift. A dead thing feels no pain; a dead thing feels no grief, either.

When we grieve, we are experiencing the fullness of being alive, and having loved. Love, after all, is nothing less than a commitment to future grief; all things end, one way or another, and when something we love ends, grief is inevitable. I love deeply and wholly. I love my friends, who are so relentlessly wonderful, and who carried me, and who have taught me so much. I love my family, and I hope to love even more family in the future.

I love being alive.

And when it hurts to be alive–when my mouth is alight with agony, when my earlobe is burning thanks to a new hole, when my skin flinches under the needles of a tattoo gun–when my heart is curled in on itself with the unthinkable horror of loss–I love the way it hurts, too.

Because the pain is part of it all. The pain is one of the privileges of being alive.

And I wouldn’t give it up for anything.

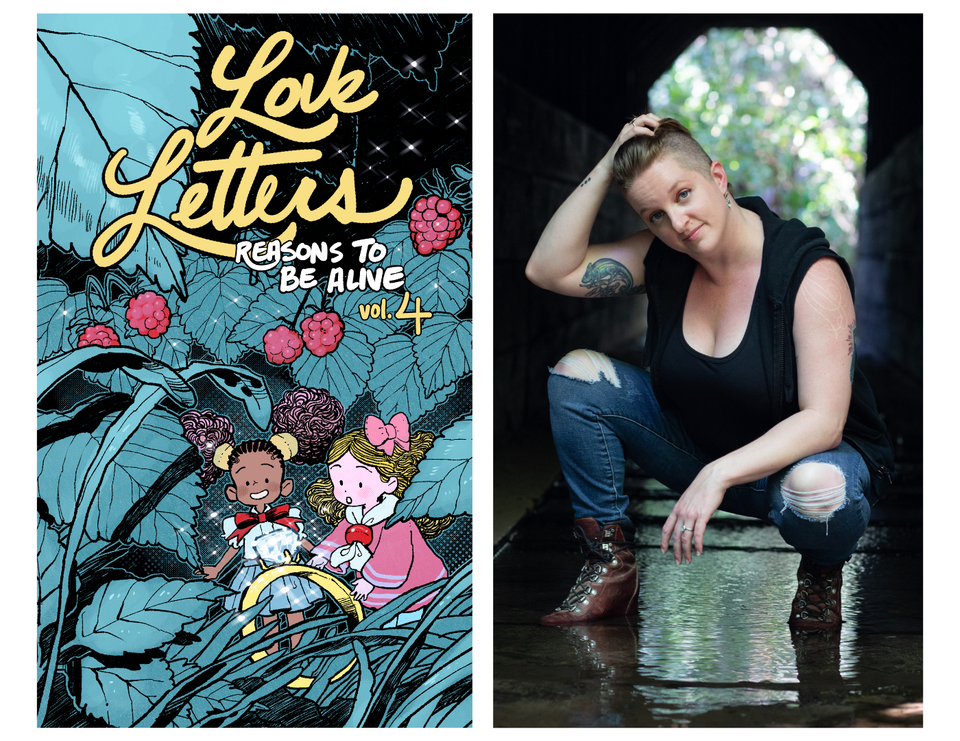

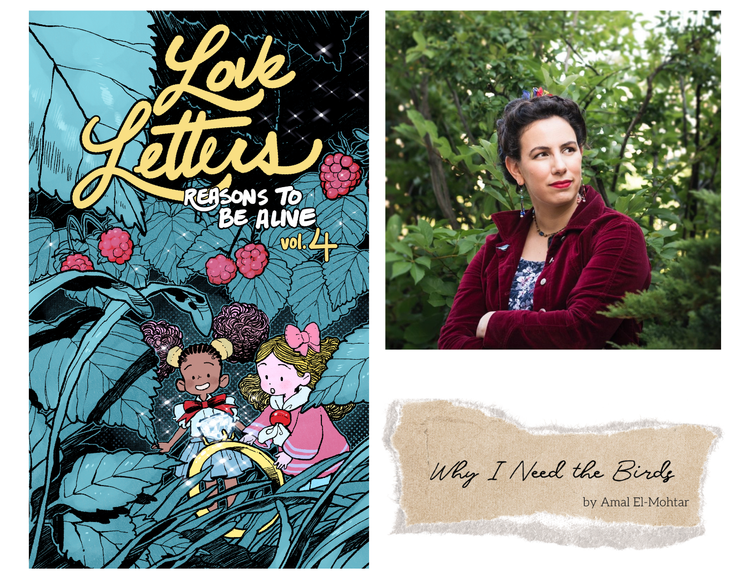

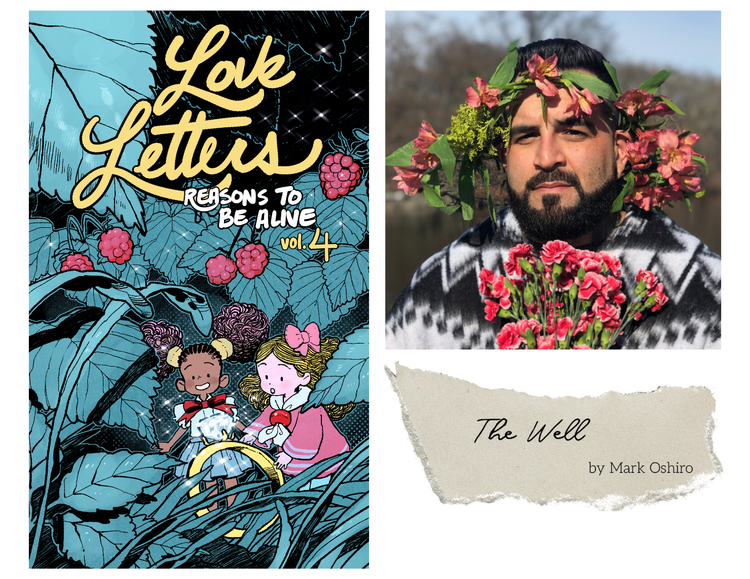

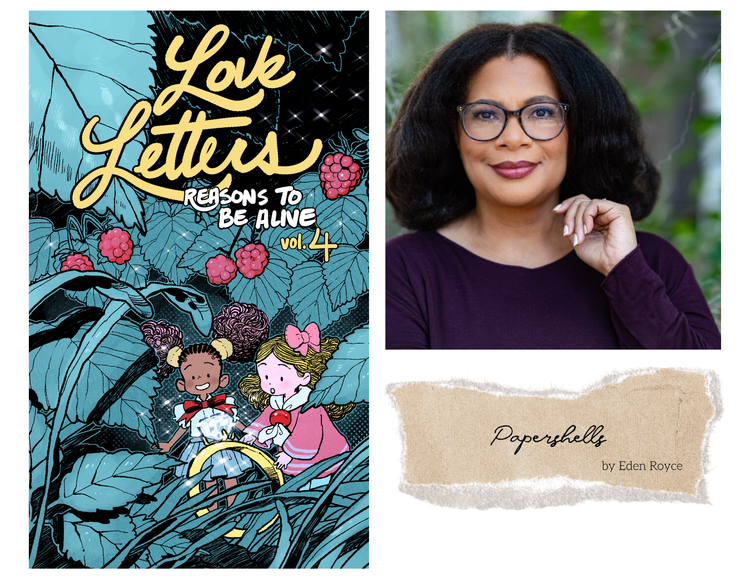

Love Letters: Reasons to Be Alive is a yearlong essay series in which we acknowledge, celebrate, and examine the objects and experiences that keep us going, even through the hardest of times. The series is free to read, for everyone, forever.

If you'd like to support the work of the team that makes this series and keeps Stone Soup running, you can subscribe here for as little as $1 per month, or you can drop a one-time donation into the tip jar.

In the meantime, remember: Do what you can. Care for yourself and the people around you. Believe that the world can be better than it is now. Never give up.

Sarah Gailey - Editor

Josh Storey - Production Assistant | Lydia Rogue - Copyeditor

Shing Yin Khor - Project Advisor | Kate Burgener - Production Designer

Member discussion