Personal Canons: Dealing With Dragons

Dealing With Dragons is the first book in Patricia C. Wrede’s Enchanted Forest Chronicles. On the surface, the story is relatively simple — Princess Cimorene, tired of the limitations of her station and the expectations of society, runs away from home. The plot follows the Princess as she learns how to live with and care for dragons, and as she uncovers (and foils) a secret plot to assassinate the dragon king and steal the throne.

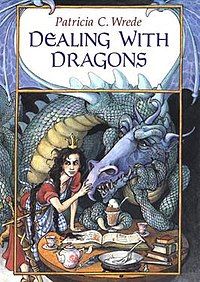

When I first picked up Dealing With Dragons as a kid, I remember looking at the cover and thinking who is she? The young woman on the cover looked grouchy and a little wild. She looked like she had secrets, some of them unsavory. She looked like the girl of my dreams. I was completely entranced.

In the introduction to the twenty-fifth anniversary edition of Dealing With Dragons, Patricia C. Wrede notes how puzzling she finds the assumption that the character of Princess Cimorene — who rejects suitors and prefers fencing to embroidery — was written as a feminist statement about what women can accomplish. “My real-life family and friends are full of women like Cimorene,” she writes. “They aren’t proving a point about what women could, should, or can do; they are ignoring that whole question (which none of them considers a question worth asking at all) and getting on with doing the things that interest them most.”

Wrede brings that exact philosophy into Dealing With Dragons. Although it engages with the expectations that are set for Cimorene and for women in general, it doesn’t make a project of affirming or rejecting those expectations. It doesn’t seem to care much about them at all.

I knew that Dealing With Dragons was part of my personal canon, but upon revisiting it in preparation for writing about it, I was startled by how obviously this book shaped me as a reader, a writer, and a person. Wrede’s decision to ignore the questions that aren’t worth asking is clear throughout the narrative. Questions she doesn’t bother with include:

Can women do things? Interesting things?

Can women be friends with other women?

Do women who dislike each other still think of each other as people?

Is labor that is traditionally assigned to women valuable?

Is gender a binary construct?

Does gender have to matter at all?

Is it bad to be disinterested in romantic and sexual attraction? Is it bad to be interested?

Is it okay to Be Like Other Girls?

Wrede and her characters largely disregard these questions in Dealing With Dragons. There’s casual mention of dragons who haven’t settled on a particular gender identity. There are nuanced relationships that fall well outside of stereotypical gender roles. Princess Cimorene chafes not at expectations of feminine behavior, but at the boredom and constriction that comes with her station. She doesn’t want to be considered a romantic prospect, and doesn’t question her own position on the matter. The narrative highlights that she is practical and impatient, curious and competent — a person in her own right, rather than an archetype or an anti-archetype. She treats other people are individuals, not as categories.

For a young queer reader who was just starting to consciously consider the idea of categories — who was just starting to think about all the questions Wrede chose to sidestep in this book — Dealing With Dragons was a revelation. Maybe, the book suggested, all those hard questions weren’t necessary after all. Maybe life could proceed without them.

Of course that’s not how things work out. The world we live in asks those questions and more like them constantly; it forces me and others like me to answer those questions again and again, forever. But to a young queer kid who was facing down that future, the idea of getting to dodge those questions altogether was a beacon of hope. Maybe, Dealing With Dragons whispered, nobody will care about that stuff. Maybe you can be who you are without having to explain it to anyone.

The still-plastic tissue of my brain unfolded to let that notion in, and I’ve never quite been able let it go since. Genre fiction continues to hold a vague promise to me that there can be infinite worlds, including worlds without the hard questions, the boring questions, the hurtful questions. Sometimes that idea serves me well and sometimes it doesn’t, but either way — it’s right there, plain as day, in the things I write and the things I say and the things I do and the person who I am.

I’ve spent a good part of my life in pursuit of that dream. In my writing, I tend to brush past explanations that I find boring, like how does the magic work or why does that character use they/them pronouns. I expect that the reader will trust me enough to come with me through the story — an expectation that sometimes leads me to underthink my worldbuilding or fail to describe characters. (I owe my editors a significant debt of gratitude for catching the lapses, and for supporting the risks.)

Of course influence doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Wrede’s writing didn’t only change how I think about my work. It also changed how I think about my life. I tend to question everything, to overthink and overanalyze myself and the world around me — but there are some questions I’d prefer to simply ignore.

Can a person’s understanding of their own gender change over time?

Is sexuality rigid?

Can a religious person be queer? Can a queer person be religious?

Can a person love more than one partner?

Can there be joy after immense trauma and loss?

I’d rather not bother with those questions, because they boil down to “are you allowed to be like this?” I’m not interested in asking that question, and I grow irritated when I have to take the time to answer it. I’d much rather live my life and be who I am and find other, more important questions to ask, like what new horizons await us and how do we love and care for each other when we are hurting and what can we build together?

Sometimes, the hard, boring, hurtful questions are important. Sometimes they can move us to interrogate our assumptions, to examine the rules we take for granted. Sometimes asking them can help us grow.

But learning when to let those questions go is an exercise in unhindered flight. It is an open window, a strong wind, and an infinite horizon. Patricia C. Wrede and Princess Cimorene taught me not to let the unnecessary questions weigh me down, and I will always be thankful to them for it.

Personal Canons is a series exploring the works of genre fiction that have shaped us as readers, writers, and people. This series features contributions by established authors, new and aspiring authors, readers, and fans. Submissions are open through August 18th.

Guidelines: 1000 words maximum, $100 payment on acceptance. Send submissions to stonesoup.substack@gmail.com. With many thanks to those who have generously donated funds to expand the series, including Kristin Harrington and an anonymous donor, 8 pieces will be accepted and published over the course of the next few months.

Member discussion