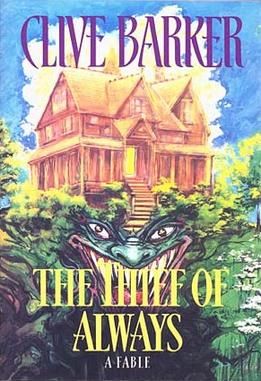

Personal Canons: The Thief of Always

“The great gray beast February had eaten Harvey Swick alive. Here he was, buried in the belly of that smothering month, wondering if he would ever find his way out through the cold coils that lay between here and Easter.”

That is the opening paragraph of The Thief of Always by Clive Barker, and it is better than anything I will ever write in all my wretched days. I reread the first page of The Thief of Always every time I am about to start writing a new project as a reminder that this is what I’m reaching for: an opening line that digs itself deep under the skin of the reader and stays there for life.

The Thief of Always is about Harvey Swick, a boy who is consumed by the kind of soul-numbing boredom that is only possible when you are eleven years old. He’s approached by a man named Rictus, who offers him entry into paradise: Holiday House, a place where he can have anything and everything he wants, every day, forever. It is a place where he will never, ever get bored. After thinking it over for a little while, he accepts the invitation. As anyone who is familiar with Barker’s work might guess, Harvey Swick then proceeds to learn the cost of getting everything you ask for.

This book was my first real encounter with horror. I had spent plenty of time tearing through stacks of Goosebumps and Fear Street books, but none of them unsettled me viscerally — they offered me a safe kind of fear that I could walk away from feeling satisfied. The Thief of Always is another kind of beast altogether. It’s intended for children, but it’s written as if children are capable of experiencing real trauma and terror, as if they should be allowed to know fear and uncertainty.

Barker is not known for writing books that are particularly easy on the reader. His work is not always kind — he steers into the innate horror of embodiment in a way that is sometimes cruel to those whose bodies are already devalued by contemporary Western society. He treats all bodies as potentially grotesque, but one cannot separate a work of body horror from the context of a culture that treats some bodies as grotesque by default. I would love Barker’s work even more if it existed in a vacuum and didn’t have the potential to reinforce the harm caused by that cruel culture.

This is more evident to me as an adult than it was as a child — when I first read The Thief of Always, I didn’t have the same critical lens toward representation and inclusion that I do now. That occasional step into cruelty makes the impact this book had on me difficult to communicate. It shaped my perspective on writing so profoundly that I consider it one of the books that taught me how to write.

Clive Barker taught me how to respect my reader.

The Thief of Always was the first book I read that didn’t once pause to see if I was keeping up. There is a conversation happening between the writer and the reader, and the conversation is fast, challenging, and direct. The narrative is quick and sharp and doesn’t pull punches. The characters endure very real loss, pain, and fear. Their relationships with each other aren’t tidy or simple, and the resolution isn’t necessarily a clean one.

And it all starts with that banger of an opening paragraph. When I read that as a child, I knew that this book wasn’t going to hold anything back just because it was written for kids to read — and I was right. The Thief of Always showcases the unique way in which Barker treats the reader as his equal. In that opening line, he offers a kind of partnership: you, the reader, get to actively participate in the process of being unsettled. There are no tricks here, and there is no guile. You and the author are in this together.

That level of respect and collaboration between writer and reader is something I experienced for the first time in The Thief of Always, and it’s something I strive to bring into everything I create, regardless of the age of my target audience. It can be easy, as an author, to forget how much readers are capable of carrying; it can be easy to decide on what a reader can or can’t handle. That is the way of safe choices, of simplistic character motives, of predictable and easy plotlines.

I could go that route — but Barker taught me that I can trust my reader to be an active participant in the work. He taught me to respect what the reader brings to the table. He taught me how to write with a sense of collaboration rather than condescension.

That perspective on writing opens infinite doors. It invites risk and exploration and honesty. Having a partner in the reader lets me expand the limitations I would otherwise put on my own storytelling. As a writer, I get to invite the reader to join me in the story, and I never have to be afraid that I’m on my own in the narrative.

No one has invited me to the Holiday House. There is no grinning conman who will rescue me from the great gray beast February when it descends upon me. But thanks to the lessons I learned from Clive Barker’s writing, I am never really at risk of getting bored.

Personal Canons is a series exploring the works of genre fiction that have shaped us as readers, writers, and people. This series features contributions by established authors, new and aspiring authors, readers, and fans. Submissions are open through August 18th.

Guidelines: 1000 words maximum, $100 payment on acceptance. Send submissions to stonesoup.substack@gmail.com. With many thanks to those who have generously donated funds to expand the series, including Kristin Harrington and an anonymous donor, 8 pieces will be accepted and published over the course of the next few months.

Member discussion